IDEAS

Missouri students benefit from principals’ leadership development

By Paul Katnik

Categories: Data, Leadership, Outcomes, System leadershipJune 2024

With targeted leadership support, Missouri principals are staying in their jobs longer and having a positive impact on student achievement. That’s according to annual evaluations over the past five years of the Missouri Leadership Development System (MLDS), a multiyear, multistakeholder effort to grow the state’s school leaders. As opposed to a one-time program, MLDS is a systemic approach to supporting principals and assistant principals at all levels of experience. Even through the tough years of the COVID-19 pandemic, participating principals felt connected, supported, and able to weather the challenges facing schools.

Eight years ago, the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education came together with the state’s leadership associations, regional service centers, and higher education institutions to act on research about the importance of school leadership. The Wallace Foundation had funded and published a synthesis of two decades of research on leadership, which found that principals have a measurable impact on student achievement (Leithwood et al., 2004).

As the foundation has continued to support research on leadership, we have learned that the impact is even larger than originally thought (Grissom et al., 2021). Principals not only matter — they matter a lot. One of the major findings of the latest review was that moving principals from average to above average performance gives every student in a school three extra months of academic gain. It also creates better school culture and climate for all students, staff, and parents.

The authors of the report wrote, “It’s difficult to imagine an investment with a higher ceiling on its potential return than a successful effort to improve leadership” (Grissom et al., 2021, p. xiv).

In Missouri, we have made that investment, using federal Title IIA funds, and are seeing the returns grow every year. Title IIA is part of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the U.S.’s main source of federal funding for professional learning, and it includes a 3% set-aside that states can use to support leaders’ learning and development. With that funding, we have been able to develop, implement, and evaluate a system of support and facilitated learning opportunities that ensure principals have what they need to lead effective teaching and learning in their schools.

As Margie Vandeven, Missouri’s commissioner of education, said, we can either “let trial and error serve as the lead instructor, or we can be more intentional.” Vandeven added, “Through the implementation of the Missouri Leadership Development System, we choose to cultivate improved leadership practice by engaging our principals in relevant and meaningful learning over the course of their entire career” (Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, 2020, p. 2).

Principals not only matter — they matter a lot. With federal Title IIA funds, Missouri principals are staying in their jobs longer and positively impacting student achievement. Learn how: https://bit.ly/3VIiBTd #TheLearningPro Share on XABOUT MLDS

MLDS was developed by the state education agency in collaboration with a number of partners, including both of Missouri’s principal associations, the superintendents association, the higher education association, and regional service centers, with support and collaboration from the teacher associations and the school board association.

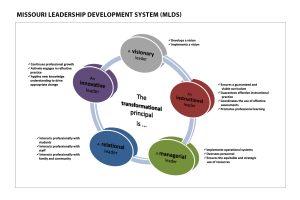

MLDS builds five connected domains of transformational leadership, which summarize the main roles a principal must assume to effectively lead a school that is focused on teaching and learning. Principals need to wear a lot of different hats, often simultaneously, and MLDS aims to make sure our leaders can wear and balance all those hats. The five domains are:

- Visionary leadership

- Instructional leadership

- Innovative leadership

- Managerial leadership

- Relational leadership

Each domain is broken down into more detailed competencies, which have been cross-walked with the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders. (See figure on p. 58.) These are similar to the domains found to be important in research about principal pipelines funded by The Wallace Foundation, including the importance of leader standards, high-quality preparation for principal candidates, aligned evaluation systems, and the importance of supervision, mentoring, and coaching (Gates et al., 2019).

The federal funds allow us to support a team of specialists, organized in nine regional hubs throughout the state, to facilitate learning about the domains and competencies, facilitate networking, and mentor principals.

The system provides four levels of learning and support for principals at all stages of development. Some principals from the original cohort that started eight years ago continue participating to continually grow their skills. The levels are:

- Aspiring (principal candidates)

- Emerging (Year 1 or 2 MLDS content)

- Developing (Year 3 or 4 MLDS content)

- Transformational (Year 5+ MLDS content)

In addition to the learning and networking for current principals, we have embedded the MLDS components into multiple policy areas in the state to create a cohesive system. These include our state standards for principals, principal preparation coursework at Missouri universities, performance assessment for principal candidates, principal certification language and requirements, the state’s mentoring requirements, the state’s evaluation model, and the microcredentials that principals can obtain for upgrading areas of principal certification.

This systemic approach and the collective ownership it inspires among all partners are key to scaling, sustaining, and succeeding with our leadership development efforts because we know that a one-off program cannot achieve the transformation students need.

GOING TO SCALE

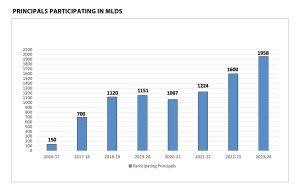

MLDS is built on the belief that all principals need and deserve support and on the recognition that scale is essential for making a difference for all students at all schools. Before MLDS, our state ran an annual leadership academy program that was popular and successful but only reached about 250 principals a year, or less than 10% of school leaders in the state. We also saw that principal turnover was too high. We recognized that we weren’t moving the needle on teacher practice or student achievement with those numbers.

Our vision for MLDS was to change that and make leadership development universal. Every year, we are getting closer to that goal. Over the past eight years, there has been a steady increase in participation in MLDS, even through the years of the pandemic. (See graph on p. 59.) In 2023, the vast majority of districts’ principals and assistant principals (87%) participated in MLDS, along with 38% of charter school principals.

This saturation is important because it is clear that common language across schools and districts is a necessary component for school improvement, yet it’s very difficult to accomplish. MLDS has allowed us to create common leadership language so that when a school or district loses a principal and hires a new one, that principal will bring their MLDS experience and leadership skill with them. That creates consistency for schools, teachers, and students and makes everyone more likely to succeed. This occurs regardless of whether the principal is a veteran or novice leader because MLDS content is being taught in each of the 23 principal preparation programs in our state and across veteran principals’ levels of experience.

RESULTS: HIGHER STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT AND PRINCIPAL RETENTION

We conduct an evaluation of MLDS every year, and results can be found at dese.mo.gov/educator-quality/educator-development/missouri-leadership-development-system. In the most recent evaluation, from 2023, researchers conducted surveys of 270 MLDS principals and 70 superintendents whose principals participated. They also conducted interviews with 55 people and conducted document reviews of MLDS materials. Through external evaluations, we have also gathered data from hundreds of teachers who are in schools that have an MLDS principal.

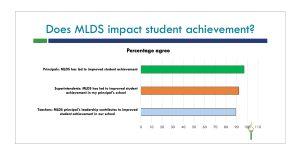

We pay close attention to the connection between principal practice and student learning. Although we recognize that it can take years for professional learning to change practice and ultimately impact student learning, we are beginning to see some signs of that impact in our data. More than 90% of principals, 90% of superintendents, and nearly 90% of teachers who are involved in and connected to MLDS believe the program makes a positive contribution to student achievement. (See graph above.)

Survey and interview data also provide detail about how MLDS is leading to improvement.

Between 90% and 100% of principals who participated in MLDS say that the program helps them strengthen their leadership practices, is relevant to their needs, and helps them grow as professionals. More than 95% say that the program makes clear connections between leadership skills and student learning and focuses on research-based leadership practices.

Similarly high percentages of superintendents who had a principal participating in MLDS say that it strengthens principals’ instructional leadership practices, makes their principals better school leaders, and supports the growth of school leaders all across the state.

Between 80% and 90% of teachers feel that MLDS has helped their principals support them and students effectively. They reported that their principals’ leadership practices strengthen classroom instruction and contribute to improved student achievement and that, because of MLDS, their principal provides them with constructive feedback that helps them be better teachers and builds positive relationships with students and staff.

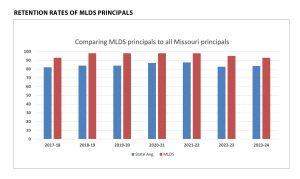

Another important indicator of success is that principals who participate in MLDS are more likely to stay in their jobs than those who do not participate. Improving principal retention rates is one of our primary goals because we know that principal turnover has a negative impact on schools, teachers, and students (Blad, 2023; Cieminski & Asmus, 2023).

The past seven consecutive years of data have shown that the retention rates of MLDS principals exceed the state’s average retention rates by over 10 percentage points each of those years. (See graph above.) Even more strikingly, we find that, due to the large number of principals now participating in MLDS, we are having a positive impact on the state’s overall average principal retention rate. These were the system-side improvements, the needles we had hoped to move, by developing the state’s leadership development system and taking it to scale.

These findings are getting noticed. In summer 2022, the state of Missouri participated in a Title IIA audit and received a commendation from the U.S. Department of Education based on the MLDS data. The commendation cited the ongoing growth and reach of the program as well as the fact that the program is grounded in research, such as the review by Jason Grissom and colleagues, and evaluation data, which we use to continually refine and adjust the services.

NEXT STEPS

Our work is not done. Our goal is to have all 3,500 principals and assistant principals in Missouri engaged in MLDS, and we are making encouraging progress toward that goal. We are also working to meet the ever-evolving needs of students and schools.

In September 2022, the U.S. Department of Education awarded a three-year SEED grant to the state of Missouri and the Community Training and Assistance Center to expand MLDS to address challenges created by the pandemic.

The specific goals of the grant are to build principals’ capacity to accelerate learning for students whose learning was disrupted; create structures and systems to address students’ increased social and emotional needs; and develop systems of teacher recruitment and retention to mitigate the teacher shortage that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

New and revised content for these three goals has been developed along with strategies for implementation with our MLDS principals. Our first round of evaluation is taking place this spring to determine the effectiveness of our efforts to increase principals’ capacity and the impact of these three goal areas on post-pandemic challenges in our schools.

Based on the decades of research about principals’ impact on student achievement (Grissom et al., 2021; Leithwood et al., 2004), we believe that supporting principals through MLDS is an essential catalyst for helping schools and students rebound from the pandemic.

As we continue with this work, we are learning from and sharing our insights with other states so we can all continue to provide the kind of leadership that schools need and students deserve. As one principal interviewed during the evaluation said, “Keep doing what you are doing. Keep it relevant. I don’t know what I would have done without MLDS. It was a huge godsend. It was the best (professional learning) I had as an educator in my 15 years.”

References

Blad, E. (2023, July 31). What new data show about principal turnover. Education Week. www.edweek.org/leadership/what-new-data-show-about-principal-turnover/2023/07

Cieminski, A. & Asmus, A. (2023, February). Principal turnover is too high. Principal supervisors can help. The Learning Professional, 44(1), 34-38.

Gates, S.M., Baird, M.D., Master, B.K., & Chavez-Herrerias, E.R. (2019). Principal pipelines: A feasible, affordable, and effective way for districts to improve schools. RAND Corporation.

Grissom, J.A., Egalite, A.J., & Lindsay, C.A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools. The Wallace Foundation.

Leithwood, K., Louis, K.S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. The Wallace Foundation.

Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. (2020). Missouri Leadership Development System. dese.mo.gov/media/pdf/oeq-ed-mldsexecutivesummary

Paul Katnik is the assistant commissioner of the Office of Educator Quality. Katnik has been in education for over three decades working with children of all ages, K-12, as both a teacher and a building principal. He has served at the Missouri Department of Education for over nearly 20 years, and has been instrumental in coordinating the state model Educator Evaluation System, revising teacher and leader preparation programs, developing the state’s Educator Equity Plan, and creating the Missouri Leadership Development System.

Categories: Data, Leadership, Outcomes, System leadership

Recent Issues

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES

June 2024

What does professional learning look like around the world? This issue...