IDEAS

Superintendents are key to principals’ professional learning

By Rafaela Espinal

Categories: Coaching, Collaboration, Continuous improvement, DataAugust 2023

We know the importance of dedicating time for teachers’ professional learning, but we often neglect to dedicate adequate time for principals’ learning and development. As a district administrator in New York City, I have learned the value of superintendents modeling direct and deliberative learning practices and processes so that principals can do the same for teachers and teachers, in turn, can do the same for students.

I recommend that superintendents take the following steps to guide their efforts to support principals’ learning:

- Get to know principals as individual learners.

- Ground the work in adult developmental theory.

- Be intentional and strategic about allocating time and resources to principals’ professional learning.

These strategies are based on research and on my experience as superintendent of Community School District 12 in the Bronx, New York City. In that district — the poorest Congressional district in the U.S. (Caliendo, 2017; Daniels et al., 2021; Johnson, 2022) — a commitment to these principles in the service of instructional leadership has helped schools achieve significant academic progress.

Get to know principals as individual learners

School leaders are learners at different levels in terms of pedagogy, leadership, and organization, so as we do with students, it’s important to begin with the learner and identify individual strengths and areas of challenge.

School leaders are learners at different levels in terms of pedagogy, leadership, and organization. As we do with students, begin with the learner and identify individual strengths and areas of challenge. #EdLeadership #ProfDev… Share on X

Superintendents and their teams need to identify specific gaps in knowledge, skills, or mindsets to anchor our goals to plan, teach, and increase the principal’s capacity. This also allows us to set measurable targets when making decisions, establishing partnerships, and allocating resources. Establishing the edge — where each challenge and strength meet — affords us the opportunity to reflect and plan the most accessible teaching or coaching strategy to reach the principal as a learner based on their level of competency.

Establishing the edge — where each challenge and strength meet — affords us the opportunity to reach the principal as a learner based on their level of competency. #principals #lifelonglearner #TheLearningPro Share on XWe can use our understanding of current strengths and needs to solidify a principal’s strengths through feedback, then connect what they already know and do well to something new. When I use this strategy, the principal and I work together to continue to make connections until principals have a self-extending system of strategic decision-making, a concept that comes from developmental reading behavior, in which the learner can build on what they know to identify and organize the right resources for filling in the things they don’t know (Clay, 1991).

As one example, principals I worked with reviewed their personal performance data during a planned day of rigorous learning on curricular expectations and equity-driven teaching. We grouped the adults strategically to provide them with differentiated, tiered models of support.

These particular middle school principals, who were grouped based on their common language and set of challenges with the students they served, were positioned to have discussions that were meaningful to them as adult learners and leaders. Together, they designed action plans that they could implement for their individual school communities.

Ground the work in adult developmental theory

Although some of the principles of teaching and learning apply to both students and adults, others do not. It is therefore critical to ground professional learning for principals in adult developmental theory and ensure that time cultivating adult learning connects theory to practice with actionable strategies and protocols for collaboration, communication, and feedback (Drago-Severson & Blum-DeStefano, 2018; Drago-Severson, 2014).

In my own learning and growth, I have internalized adult learning theories, most recently Drago-Severson’s (2012) ways of knowing based on constructive developmental theory, a framework for understanding how adults make sense and meaning from their experiences, the roles in which they serve, and themselves (Drago-Severson, 2009).

Drago-Severson’s theory holds that different people orient to the world in different ways — for example, through concrete processes and rules or through relationships and social approval. I find this approach helpful when supporting principals and other adult learners because it allows us to explore how these learners relate to themselves and each other and identify what they need and what is likely to resonate.

Create space and time for intentional learning

The best intentions and theories don’t lead to progress unless we create time and structure to put them into action. Superintendents play a key role in allocating that structure and making time for purposeful planning.

Beside my office in the district office of Community School District 12, I had a room dedicated to teaching and learning formally and informally. I named it “Rafaela’s Classroom.” It allowed me to anchor professional learning in the district office and model its importance.

As a superintendent, making time to lead professional learning for school leaders and modeling practice for principals set the direction of learning in the school and provided an opportunity for principals and teachers to replicate the learner-centered approach across all school levels.

When we structure professional learning, we need to allocate the time to build understanding over time in a series of learning cycles so that learning opportunities are not seen as one-shot deals, but as connected learning opportunities. This has scheduling implications that we need to make clear to principals and others in the district.

We should also remember that planning time is essential and must be created intentionally, including making time to find resources, articles, and books so we can anchor learning in shared texts and align language so that, as a district community, we can understand ourselves and others.

We also need to establish and articulate the purpose and goals of the professional learning. This starts with creating clear outcomes for learning sessions and developing a common language over time by sharing those intended outcomes and pointing out how they align to the district’s strategic plans and district and school goals aimed at improving teacher practice and student learning. We should communicate and reiterate these connections in agendas, facilitator guides, and other communications before and after learning sessions.

Time and communication are particularly important when we introduce principals to new curricular content or district expectations. We can support coherence by leveraging the expertise of the district staff and school leaders’ strengths to give whole-group and individual support.

And we shouldn’t lose sight of the importance of including other leaders in our efforts to introduce new initiatives and increase coherence with overarching goals and plans. For example, we can lead assistant principal study groups that align with principal development goals.

Impact of time devoted to adult learning

Measuring the degree to which professional learning for school leaders accomplishes its objectives is essential. In my experience, impact is best reflected in qualitative data. In my work in the Bronx, and now as a director working with 11 superintendents in Manhattan, I seek to gather reflections after every professional learning opportunity.

For example, in Community School District 12, after principal conferences and school support visits, we surveyed principals to evaluate the visits and conferences. I used the results to engage my cabinet and guide future opportunities and decisions. Using those results, we identified and documented best practices (e.g., videos, case studies).

We also gathered quantitative survey results after job-embedded coaching and targeted support visits (which were differentiated specifically based on the needs my team and I identified during previous visits). We found that school leaders’ confidence in facilitating professional learning to support teacher practice that improves student learning increased, and principals reported a high level of preparedness to implement all aspects of different initiatives.

We also examined data on student learning before and after we began implementing an approach to instruction and leadership that is deeply grounded in professional learning and capacity building for leaders and teachers.

When I went to the district in 2014, I found that some school leaders had forgotten what it was like to be a learner and even a struggling learner with varying challenges, so we created consistent and coherent learning opportunities that placed the leaders in the learner’s seat and promoted active engagement in deliberate practices.

We began modeling instructional leadership and best practices in adult and student learning in all our meetings and professional learning, grounding our work in research and best practices, and making time for processing and reflecting on what we were learning. As a result, we shifted the culture of adult learning and shortly began to see differences in student learning.

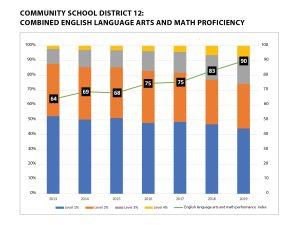

The graph above shows students’ growth in math and English language arts from 2013, the year before our team took this approach, through 2019, the year after I left the district. It includes all students, including English learners and students with disabilities. The graph shows the district’s trajectory on a measure of academic progress based on the ESSA Achievement Index.

Levels 3 and 4, represented in gray and yellow, are the levels that indicate the percentage of students making progress. The graph shows that, over time, the percentage of students falling into those progress categories increased significantly, with level 4 increasing proportionally higher than level 3, while the percentage of students falling into levels 1 and 2 decreased significantly.

The black line is a weighted average of proficiency. If the number in the black box is going up, it means any combination of moving more students from level 1 or 2 to level 3 and level 3 to level 4.

While we still need to make more progress so that all students are achieving at the highest levels, the progress made in the last few years is significant. Our students face a number of challenges, especially those related to poverty, that students in wealthier districts do not, yet they have made real strides and will continue to do so if the district stays committed to strong instructional leadership and practice.

We cannot directly attribute the progress to professional learning because the professional learning and capacity building for principals and teachers are deeply embedded in the larger instructional approach, which follows best practices for professional learning. But my research and practical experiences show that prioritizing professional learning time for teachers and principals is essential to shifting culture and instruction and therefore improving student learning.

Prioritizing professional learning time for teachers and principals is essential to shifting culture and instruction and therefore improving student learning. - Rafaela Espinal #EdLeaders Share on XBy implementing a robust instructional plan focused on developing principal instructional leadership capacity, we began to see growth.

Meeting principals’ needs

As a superintendent, devoting intentional time to professional learning helped me meet the principals’ needs. By applying adult developmental theory and a developmental model for professional learning design, educators were able to build capacity at the individual, school, and system levels that positively influenced student achievement.

By focusing on school leaders as learners, we continue to create a community of practice that reinforces coherence across schools and provides a common language within the district. Modeling the value of professional learning time through job-embedded and collaborative practices may be a missing link for superintendents in which they can invest and prioritize time. Professional learning is a resource to inspire and support all learners at all levels of a school organization.

Tips for superintendents to support schoolwide professional learning

- Prioritize time to strategically plan.

- Allocate time in principals’ schedules for professional learning, including coaching and other forms of job-embedded learning such as instructional rounds.

- Acknowledge and address the guilt school leaders often feel when taking time away from school buildings or administrative duties.

- Provide tools that will help principals make connections between professional learning and the district’s overarching mission and goals.

- Connect all levels of professional learning so the time principals, assistant principals, teacher leaders, and teachers spend coheres across all levels.

- Invite principals, teachers, and educators at all levels to lead professional learning to build ownership and empowerment.

- Shift hearts and minds to understand that continuous learning matters for leaders as well as teachers and students.

References

Caliendo, S.M. (2017). Inequality in America. Westview Press.

Clay, M.M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Heinemann.

Daniels, E., Campos, K., & Cadenhead, M. (2021, April). Ritchie Torres represents America’s poorest congressional district. He’s on a mission to save public housing. Politico. www.politico.com/news/2021/04/26/ritchie-torres-new-117th-congress-freshman-members-diversity-2021-484443

Drago-Severson, E. (2009). Leading adult learning: Supporting adult development in our schools. Corwin Press.

Drago-Severson, E. (2012). Helping educators grow: Strategies and practices for leadership development. Harvard Education Press.

Drago-Severson, E. (2014). Helping adults learn: The promise of designing spaces for development. In Drago-Severson, E., Roy, P., & von Frank, V. (2014), Reach the highest standard for professional learning. Learning Forward & Corwin.

Drago-Severson, E. & Blum-DeStefano, J. (2018). Leading change together. ASCD.

Johnson, T. (2022, March). South Bronx community nervous about new congressional district lines. The Hunts Point Express. huntspointexpress.com/2022/03/01/south-bronx-community-nervous-about-new-congressional-district-lines/

Rafaela Espinal (rye2101@tc.edu) is assistant superintendent and director of multilingual/English learners for Manhattan (Districts 1-6 and high schools) at the New York City Department of Education, an adjunct professor at City College, CUNY, and a coach for Summer Principals Academy at Teachers College, Columbia University. She was formerly the superintendent of Community School District 12 in the Bronx, New York. She is the author of the article “Superintendents can boost principals’ learning” in the August 2023 issue of The Learning Professional.

Categories: Coaching, Collaboration, Continuous improvement, Data

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...