FOCUS

Long distance leadership

By Jennifer Gill

Categories: Leadership, School leadershipJune 2020

Vol. 41, No. 3

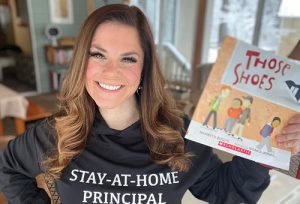

Allyson Apsey, principal of Quincy Elementary School in Zeeland, Michigan, was looking forward to the second Friday in March. It was to be a half-day for students so she and her teachers could spend the afternoon collaborating on spring lesson plans and planning the next academic year.

Then, at 11 p.m. the night before, Michigan announced that all school buildings would close after Friday to stem the spread of the coronavirus. Rumors of a closure had been swirling for days, but the announcement still came as a shock.

Apsey and her staff dismissed students at noon as planned, then huddled for an hour to eat and share their worries before heading home to tend to their own needs. To try to lighten the mood, someone decorated the dessert table with rolls of toilet paper. They left the building that day thinking they would see each other again after spring break.

It didn’t play out that way. Michigan, following other states, shuttered schools for the rest of the year, presenting principals like Apsey with a host of challenges that no leadership course could have adequately prepared them for. Chief among them: How to effectively support teachers from afar as they adjust to a new way of teaching at such an uncertain and scary time.

Four of five teachers surveyed by Education Week in April said their job is more stressful than before the pandemic (Kurtz & Herold, 2020). “Teachers’ underlying fear is that they’re not doing enough,” says Apsey. “They don’t have a picture of what great instruction looks like virtually, so when they see other teachers doing something, they’re wondering, ‘Should I be doing that, too?’ ’’

Principals from across the country share their strategies for effectively supporting #teachers as they adjust to #distancelearning amidst COVID-19. #LearnFwdTLP Share on XApsey, like other principals, has adopted several strategies to support her school’s 33 teachers during the shutdown. One is the Monday morning staff check-in, a one-question Google survey that she sends teachers to gauge how they’re feeling about the week ahead. Apsey actually started doing this earlier in the year after a teacher suggested that faculty members could benefit from routine check-ins as much as students.

When the pandemic struck, she tweaked the multiple choice answers to reflect teachers’ new reality. Responses now include: “We have sick family members, but we are doing OK” and “Please tag me in to remotely work on a project. I’m going stir-crazy.” Apsey tracks responses and flags those needing follow-up.

When a few teachers expressed interest in taking an online class about helping kids cope with trauma, for example, Apsey gave recommendations. The weekly staff check-in has been so useful that Apsey launched a similar one for school families so she could to respond to their needs, too. Roughly 40% of Quincy’s families routinely answer.

When Quincy teachers meet with their classes on Zoom, the focus is as much on connecting as teaching. The school’s 550 students all receive weekly remote learning plans prepared by the district’s curriculum team and are free to ask questions during the virtual class, but Apsey doesn’t expect teachers to hammer on multiplication drills and grammar rules. Instead, she loves seeing them get creative in building community online.

One 4th-grade teacher asked students to give 30-second reviews of books they’re reading, while in another Zoom room, 3rd graders introduced their dogs and stuffed animals to classmates. These simple interactions, she believes, give kids the social and emotional support they crave right now. Many apparently can’t get enough: One 5th-grade teacher, new to Zoom, told Apsey that his class lasted 90 minutes. The suggested time is 30.

Lead with learning

The rapid shift to remote learning has come with a steep learning curve for many teachers. Ryan Daniel is the principal of Chillum Elementary School in Hyattsville, Maryland. Some of her school’s 17 classroom teachers, particularly in the lower grades, had no experience using tools like Google Classroom.

While her school district, Prince George’s County Public Schools, offered some training, Daniel supplemented it with videos of herself using different features in Zoom and Google Classroom to help her staff get up to speed faster. Based on district guidelines, Chillum’s 389 students have two virtual lessons daily in core subjects with assignments due at the end of each week. On Sunday night, teachers send Daniel their lesson plans, which are based on topics set by the district, and she maps out which classes she’s going to visit.

Daniel is also a co-teacher in Chillum’s virtual classrooms so she can see the assignments teachers post and the work students submit — things she would easily see if she walked into their classroom at school. Knowing such details has come in handy: Once or twice during informal Zoom observations, Daniel has had to take over a lesson when the teacher’s internet connection dropped.

She averages two to three observations a day and sends digital postcards to tell her teachers how great they’re doing. She picks two staff members a day to call or text, just to see how they’re coping with all the changes and commiserate about life on the home front — Daniel and her husband, an essential worker, have two school-age children and a six-month-old. “I don’t feel like I’m the instructional leader I’m used to being, but I’m giving myself grace, the same grace that I’m giving my teachers,” she says.

Show patience and compassion

Indeed, principals stress that this is no time for extra meetings or to hold teachers to impossible standards. After all, teachers, like everyone else, are facing enormous stresses in their personal lives, too. They may have a sick loved one, a partner who lost his or her job, or children who need support with their own schooling.

At Elk Grove High School in Elk Grove Village, Illinois, principal Paul Kelly has kept staff meetings to a minimum since the closure. He carved out time in the schedule for his school’s professional learning communities to meet weekly on Zoom but did not make attendance mandatory because he recognizes that the time may not work with everyone’s home life.

''Every communication a teacher has with kids should start with patience and compassion, even more so now. It’s a lot easier for staff to do that if their boss takes the same approach.'' @EGPrinciPaul Share on X“I need to lead in a way that I want our teachers to treat our kids,” he says. “Every communication a teacher has with kids should start with patience and compassion, even more so now. It’s a lot easier for staff to do that if their boss takes the same approach.”

Many principals also have a newfound appreciation for their own professional learning circles. The National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) produced a six-part virtual town hall series for school leaders to share their experiences about leading through the crisis. Within weeks, the series garnered nearly 90,000 views; a video from NASSP typically gets a couple hundred.

“Principals need their own community to share best practices, discuss their most pressing challenges, and be open and vulnerable,” says Beverly Hutton, NASSP’s deputy executive director of programs and services. “The more they’re able to share and reflect, the better they’ll get at this.”

Stay connected

When Pilar Perossio, principal of Bancroft Middle School in Long Beach, California, feels tapped out, she taps her phone for some encouragement. She and the seven other middle school principals in the Long Beach Unified School District created a group on WhatsApp to stay connected. Calling themselves the Survival Group, they’ve brainstormed ideas for end-of-year 8th-grade activities, suggested ways to celebrate Teacher Appreciation Week, discussed platforms for making a faculty video, and shared concerns about students who’ve gone missing since the closure.

About 85% of Bancroft’s 1,000 students log in regularly, and Perossio’s support team follows up with calls and emails to the rest. Working with district curriculum leaders, Perossio and her teachers have modified learning plans to focus on the most essential standards so students are ready for the fall. Like principals across the country, she wonders what school may look like then. Will schools have to limit the number of students in a class? Will they have to rethink how kids move between classrooms?

While there are many unknowns, Hutton believes there will be a silver lining to the school closures. For one, the pandemic shined a light on inequalities in student access to technology at home and ways to remedy it. Teachers who once balked at using online tools are now proficient, or at least more comfortable, with them. Principals have discovered new ways of communicating with key stakeholders.

One school leader told Hutton that in the prepandemic days of in-person community meetings, she was lucky if 25 people attended. When she hosted a Zoom call after the school closure, 150 parents joined. The strong turnout may have stemmed from the uncertainty surrounding the shutdown, but Hutton is hopeful that newly forged connections like this stick.

After all, educators tell students all the time that they’re teaching them to be lifelong learners. Now the field has a chance to model that practice for them. “If we look at this crisis as a prolonged interruption until we get back to the way things used to be, we’re missing the opportunity,” she says.

Monday morning check-in (COVID-19 edition)

- How are you feeling?

- We are doing well. I feel good about our plan for the week.

- We are doing OK, thankful we are not sick.

- We have sick family members, but we are doing OK.

- Please call me, I need some TLC.

- Please tag me in to remotely work on a project. I am going stir-crazy.

- I would love to connect virtually to learn together (book study, etc.).

- I am not doing well at all, either physically or emotionally, and would love some help.

- Other:

References

Kurtz, H.Y. & Herold, B. (2020, April 27). Opinion of Devos plunging, truancy rising: 10 key findings from latest EdWeek survey. Education Week. www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/04/27/opinion-of-devos-plunging-truancy-rising-10.html.

Categories: Leadership, School leadership

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...