FOCUS

6 things I wish I’d known as a new coach

By Sharron Helmke

Categories: Coaching, FundamentalsApril 2025

Instructional coaches play an integral part in job-embedded professional learning. We help teachers understand how to meet the specific needs of their student populations while implementing their district’s high-quality curriculum resources and instructional strategies. It’s our work with teacher teams and individuals that transforms information learned during a workshop from cognitive understanding to real-world strategies that make a difference for students.

But the coaching role is not always clear to those just starting out in the position, or to the people they work with. Coaches often cite being of service to others and making a meaningful contribution as strong personal values. Many have been encouraged to become coaches by people who have praised their helpfulness or their heartfelt desire to be useful. This is where role confusion often starts, because a coach’s work is not to be a teacher helper or an advocate for overworked teachers. The goal of coaching is to advance student outcomes by working with teachers to improve their understanding and implementation of curriculum and district resources. The coach’s loyalty and priorities must reside with students.

Keeping this purpose and these priorities in mind is essential for new coaches. Doing so will ensure that you get off to the right start and that the relationships and patterns established in the first few months of the school year will lead to productive efforts for both teachers and students. When I was a new instructional coach in a district where coaching was novel and not well-defined, I struggled to delineate my relationship with teachers and students and to articulate the changes that were needed. Looking back over a decade later, I see how much more teachers and students would have benefited if I had had a clearer understanding of my role.

To support coaches just starting in their role — and experienced coaches still struggling to define their role — I’ve pinpointed a few things that I wish had been made clearer to me. My hope is that having this clarity will help other coaches understand not only what their role is, but how they can best find meaning in their work and see their impact for students.

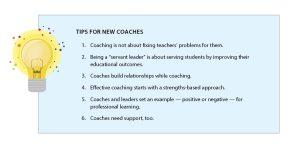

1. Coaching is not about fixing teachers’ problems for them.

People new to coaching often assume they have to identify and solve the problems teachers bring to them, or fix what they see as flaws in a teacher’s instruction. The most important lesson I’ve learned about coaching is that it is not my job to do either of these things. As a coach, I’m most effective when I focus on helping teachers understand where they are feeling stuck and why, and support their efforts to surface new alternatives or ideas. In my experience, once people can pinpoint their stumbling blocks and have support to think about possibilities instead of limitations, they find their own solutions. My job as a coach is to help teachers process their own thinking by asking questions and reflecting back what I hear, rather than superimposing my solutions over theirs.

I encourage coaches to clarify this at the beginning of the year, and even at the beginning of every subsequent coaching conversation. You can say something like, “I’m here to help you explore your own thoughts and identify an action step. I’m not here to tell you what to do or give you advice.”

2. Being a “servant leader” is about serving students by improving their educational outcomes.

When I discourage coaches from acting as teacher helpers, they often respond by saying, “But I want to be a servant leader.” Being a servant leader doesn’t mean you serve the adult you’re working with; it means you serve the bigger cause that brings you both together, which is student achievement. In other words, servant leadership isn’t about making copies or covering lunch duty. It’s about asking the difficult questions to make educators think critically about their current practice, its impact on student outcomes, and how they can meet student needs that are not yet being adequately addressed.

It’s important for coaches (or leaders who have coaching in their roles) to understand this from day one, because it’s easy to fall into a pattern of helping behaviors and expectations. Like all professionals, coaches tend to get clearer about their responsibilities and skills over time, but starting off with clear expectations can prevent a lot of problems down the road.

Understanding the distinction between helping and coaching is also useful for deciding how to spend time and what to prioritize. There is never enough time to do all the things we know are important, so we have to choose wisely. I find that coaches sometimes think they need to earn their way into classrooms, so they will bend over backwards to do almost every task a teacher asks of them. Soon their calendars are full, they’re running themselves ragged, and they’re not getting to the real work of coaching.

A coach’s time is a valuable resource that must be deployed in ways that make the biggest difference for the largest number of students. If you find it difficult to set boundaries, it can be helpful to remember that time is money. I often say to administrators, “If you had a $60,000 resource sitting in your supply closet, would you just let it sit there?” If a coach is stuck in their office all day analyzing data or covering as a classroom sub, that’s like locking that resource in the closet.

3. Coaches build relationships while coaching.

We hope coaches, even brand-new ones, know relationships are essential. But sometimes coaches hear misguided advice that they should engage in a separate relationship-building phase before getting into the work of coaching. This is counterproductive. If you try to build relationships by, say, bonding over shared interests, you send the wrong message about what the coaching role is about. When a teacher sees you as a friend rather than as a coach, they are likely to see you as someone they can vent to. Then when the teacher expects you to support their grievances, it can make coaching impossible. As a coach, you should gently challenge the desire to place blame or ruminate rather than supporting or condoning those habits.

When coaching is done well, relationship-building is embedded in the process. Coaches forge connections by giving their full and undivided attention to the person with whom they are speaking, asking questions without judgment, listening patiently and with empathy, honoring confidentiality, and focusing on the problem of practice at hand. They communicate respect by showing their trust in a teacher’s ability to solve their own problems by saying, “I value you enough to be curious about your thinking and to respect your professional ability and judgment.”

Remember that relationship-building is ongoing, not a discrete activity that occurs in a prescribed period of time. As you show value for a teacher’s time and ideas, you are continually building on a solid foundation and gradually inviting ever deeper coaching conversations that tackle increasingly sticky problems of practice. Notice the mutuality of this approach; the coach is not pushing or pulling the teacher into change; the two professionals are growing together, each in their respective skills.

4. Effective coaching starts with a strengths-based approach.

Teaching can look very different from classroom to classroom, in part because teachers have different strengths. An effective way to approach coaching is to enter every classroom and every conversation with a goal of identifying what the teacher is doing well. I enter classrooms with the following question in mind: “What is going well here and how are students benefitting from that?” Not only is looking for a teacher’s strengths far more respectful than fault-finding, it also helps a coach identify areas upon which a teacher can build their skills.

When we enter a teacher’s classroom looking for ways to help them improve or with an eye toward diagnosing and tackling flaws, our mindset has already established a pattern of thinking about what we can do to or for them. This puts us and our coaching in an antithetical relationship to the teacher rather than in a relationship of mutual respect and partnership. Looking for a teacher’s strengths and gifts allows us to coach them from a position of respect.

5. Coaches and leaders set an example — positive or negative — for professional learning.

Teachers look to coaches and administrators as models of acceptable behaviors and attitudes, even when we — and they — don’t realize it. As one of a small group of leaders, you stand out, so teachers notice your behavior and see it as an example of what is expected and acceptable. As a result, the way you act in meetings, learning sessions, and classrooms sets the tone for how others will act. If you’re attending a professional learning session with teachers and you multitask or look bored, teachers will see that behavior as acceptable and may engage in it themselves. Even if you’ve sat through the same session 10 times before, you need to model enthusiasm and engagement for the teachers around you.

Coaches and leaders should also set the right tone for others by modeling enthusiasm for district and school initiatives. That doesn’t mean you have to eagerly jump on board with every decision or that you can’t have questions, but it does mean you should resist the urge to vent or make negative comments or gestures. There is a correct time, place, and method for expressing your concerns, and you can model that for teachers.

For example, you can pose a question to a district leader such as, “Can you please explain more about that?” or, “How will we know if we have taken the right approach?” You can ask about the data the decision was based upon, the vision for the impact of the change, or the timeline for adoption. You can even ask about the ability of a school, team, or teacher to adopt a new resource or strategy. In short, you can seek clarity but you should avoid passing judgment before learning more, because that is what you also expect from teachers.

6. Coaches need support, too.

We all need social support, especially when working in a job as emotionally taxing as coaching others. It’s important to find at least one person who can relate to your role but doesn’t work in your school, someone you can talk to about this work being hard and lonely and sometimes frustrating. Attend networking events, join a professional association like Learning Forward, and use your informal professional network or your digital connections. When you find your people, be explicit in asking for and giving commitments of confidentiality. Even if your new acquaintance lives across the country, remember that education can sometimes feel like a very small community, and nothing will torpedo a coach’s career faster than news that the coach has been feeling frustrated, disappointed, or stressed by their work or the staff at the school.

I also recommend finding a mentor. A mentor is not the same as a friend, a peer, a supervisor, or a coach, but is someone who has successfully navigated the position you’re in and is willing to tell you about their experiences and share their hard-won lessons. They can help you avoid some of the missteps that set back or derailed the careers of others. It’s not always easy to find a mentor, but it’s worth keeping your eyes and ears open both within and outside your school system. Look for someone who seems to take a professional interest in you yet holds themselves at a bit of a distance. When you believe you might be speaking with a potential mentor, listen carefully to the experiences they share, ask questions about their learning from the events they recount, and ask what they would have done differently.

AN EFFECTIVE COACH KEEPS LEARNING

Even when you have the six strategies and supports I’ve described here in place, you will make mistakes as a new coach. When you do, take responsibility for your choices and your actions, apologize as appropriate, and start again with a focus on rebuilding trust. Each coaching conversation and interaction will make you a better coach if you reflect on it and grow from it. Even with years of experience behind me, I always say I’m still learning to coach. But any mistakes I make now are completely different from those I made in my early years of coaching. That’s a sign of growth. And that growth is not only good for me, it makes a difference for teachers and students.

Sharron Helmke, senior vice president of professional services at Learning Forward, designs and manages the organization’s consulting service programs that support state, regional, and local organizations in translating their improvement and learning goals into custom-designed high-quality professional learning programs that result in scalable and sustainable change. During her twenty-plus years in education she has served in a variety of roles at the campus and district levels, including teacher, instructional coach, and district-based program administrator. She is an international coaching federation certified professional coach, a Gestalt professional coach, and a trauma-informed care provider, all of which inform her approach to supporting educators. She is the author of numerous professional articles, including “To make a difference for every student, give every new teacher a mentor” in the August 2022 issue of The Learning Journal.

Categories: Coaching, Fundamentals

Recent Issues

LEARNING COMMUNITIES FOR LEADERS

October 2025

Leaders need opportunities to connect, learn, and grow with peers just as...

MAXIMIZING RESOURCES

August 2025

This issue offers advice about making the most of professional learning...

MEASURING LEARNING

June 2025

To know if your professional learning is successful, measure educators’...

NAVIGATING NEW ROLES

April 2025

Whether you’re new to your role or supporting others who are new,...