FOCUS

Good ideas spread when schools learn from each other

By Stacey Caillier and Sofia Tannenhaus

Categories: Improvement science/networks, Learning communities, Reaching all studentsApril 2023

Tom Gaines leaned over his lunch plate, listening intently to two recent graduates from High Tech High International in San Diego, California, who were now enrolled in college. He wanted to know how their high school had supported them in applying to and enrolling in college.

An educator at a neighboring high school, Gaines figured that if he could learn what had worked at High Tech High International, a school that had achieved strikingly high enrollment in four-year colleges for traditionally underrepresented students, he could work with his colleagues to integrate similar ideas at their school. Like High Tech High International, Gaines’ school served large percentages of students of color and those experiencing poverty and was aiming to increase their rates of college enrollment and graduation.

In between bites of falafel and hummus, the first-generation students talked enthusiastically about the one-on-one meetings they had with their school’s college advisor to craft a balanced list of college options. They talked about their 12th-grade math teacher, who made sure that every student completed a finance project in class so they could see college as a financial reality and who dedicated class time to helping students complete Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and Dream Act applications.

They also described school-sponsored college campus visits throughout their four years of high school, a daylong event for seniors that provided real-time support to submit their applications, and the campus visits they took once they had decided where to enroll. They explained the many opportunities they had to talk about their fears and challenges on the path to college and how teachers and counselors had helped students address them.

Using an active listening approach called an empathy interview, Gaines asked questions and took copious notes, preparing to share what he had learned with colleagues. He was especially struck by what the students described as a system of supports, not a single strategy, for improving college access. As he finished his lunch, he prepared to meet with a team from his school and from High Tech High International to share his observations and discuss how they might adopt or adapt some of the school’s ideas.

Schools can replicate and adapt success stories through networks. One way to do this is through a “live case,” where teams of professionals study what’s working in one another’s contexts. #TheLearningPro Share on XGaines and his colleagues were participating in a “live case,” a way for teams of professionals to learn from what’s working in one another’s contexts. Both High Tech High International and Gaines’ school are part of the CARPE College Access Network, a coalition of 30 schools across Southern California working to ensure that more students who are Black, Latinx, Indigenous, or experiencing poverty apply to and enroll in colleges where they are most likely to graduate.

The network includes school site teams composed of school counselors, teachers, administrators, and students. We (the authors of this article) are part of the network hub team, which provides support to those team members to use continuous improvement processes in their work. The live case is one way we connect schools in the network to learn with and from each other.

Learning what works

In a recent workshop we attended, Lloyd Provost, an expert in improvement science in the health care field, said the purpose of networks is to learn from variation. The idea is that, in any network, there will be people or organizations getting different results. If you can learn what is working, and what is not, in different contexts, you can harness the power of the collective to understand “what works for whom, under what conditions” and spread good ideas. As educators, we have long valued networks for this purpose.

But a couple of years into CARPE, our hub team read Shattering Inequities by Robin Avelar La Salle & Ruth S. Johnson (2019). In it, they talk about how the very existence of “bright spots” — or positive outliers in the data — undermines the pursuit of equity. If there are “bright spots,” by definition there are spots that are less bright, which means not everyone is being served well. “A star does not a constellation make,” the authors write.

As leaders for equity, we cannot be content to have a few brightly shining stars. We do this work because we want to create more consistently reliable and equitable systems, where a student’s experiences and outcomes are not dependent on which school or class they attend, let alone the color of their skin or their family’s socioeconomic status.

We would add to Provost’s statement that the purpose of learning from variation is to create constellations. That is the philosophy that guides our network: If we set up meaningful opportunities for schools and educators to learn from each other, we can discover how to become a constellation of shining stars for all of our students.

Around the same time that we read Shattering Inequities, one of us interviewed Don Berwick for the High Tech High Unboxed podcast (Caillier, 2021). Berwick, former president of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, has launched and supported multiple collaborative networks focused on improving critical processes in health care and patient outcomes. He described a live case as a promising structure to reduce variation across a system by having hospitals learn from those in the system that are getting the best results.

Inspired by the success of live cases in health care, we adopted the approach with our network of schools.

How to conduct a live case

In a live case, visiting teams spend a few hours at a host team school, learning what the host does to get positive results. For the live case described above, Gaines’ school team was visiting High Tech High International to learn more about the school’s success in helping traditionally underrepresented students get to four-year colleges.

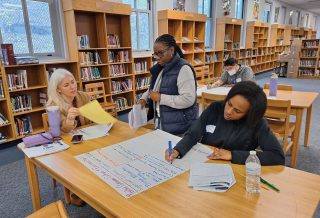

Visiting team members talk to educators, students, and alumni and, when possible, they also observe the host team’s processes in action. For example, during one live case we facilitated, the visiting team attended college application workshops in senior English classes and talked with students and faculty about them.

After this data gathering, the visiting team shares findings with the host team in the form of celebrations, noticings, wonderings, and its own learnings, and the host team has a chance to reflect and ask questions. The goal of this approach is reciprocal learning, where each team is adding value to the other’s work.

The visiting team not only comes away with new ideas to try, but also helps the host team gain insight into what parts of the process are working well and where the team might improve. We close with a debrief of the process and sharing of takeaways or implications for our own work.

The host team and visiting team then become a teaching team that shares with the whole network so that good ideas can spread. In CARPE, the teaching teams present and interact with other network members during network convenings. They model how to learn about and translate high-leverage practices from one context to another and highlight the details that allow people to turn good ideas into reality.

Essential elements for success

Here are some of the lessons we’ve learned about making live cases as productive as possible.

Get clear on the process you want to improve. To identify a process that is critical to the outcomes you care most about, it is helpful to look at data across the network or district and identify where there is large variation. Across CARPE, we saw significant variation in student enrollment in four-year colleges so we decided to focus on the process of supporting students to apply to four-year colleges, with a particular emphasis on ensuring that students apply to colleges with high graduation rates.

Identify who is getting great results and invite them to be the host team. When we looked at data, High Tech High International emerged as particularly successful in sending students who are Black, Latinx, Indigenous, or experiencing poverty to colleges with high predicted graduation rates. We also knew that the school’s team would see the live case as an opportunity to learn and improve its own process as it had consistently demonstrated curiosity and humility, a commitment to reflect and learn from data, and a pattern of following through on action steps.

Choose a visiting team. We find it helpful to choose a visiting team that shares a similar context to the host team (e.g., similar student demographics, similar size, same district). This helps teams avoid the common “well, we can’t do that at our school” excuse because the host team is like them and getting substantially better results.

In this selection process, we encourage organizers to avoid two temptations. First, you may be tempted to look at your data and identify the team or school with the poorest results on the outcome or process you care about. But remember that it’s important for the visiting team members to be curious, open to new ideas, and willing to be vulnerable about the ways their current process is not working for the students they most want to serve.

Before inviting the team with the poorest results, consider: Is the team getting those results because it does not embody those characteristics of a learning stance? Is there another team that is more open to learning and still has room to grow?

Second, you may be tempted to invite lots of teams to visit. However, the teams that participated in our live cases appreciated the intimacy that keeping it small provided. They felt more willing to ask detailed questions and share their own fears or challenges. It was often in these moments where the richest dialogue happened.

For example, when Gaines said that some teachers at his school were reluctant to offer class time and assign credit for completing the FAFSA application because it was unrelated to course content, High Tech High International’s 12th-grade math teacher responded with an impassioned reflection on how his thinking had evolved on this topic. He also said that he doesn’t penalize students who don’t complete the application.

This level of nuanced discussion about how the process worked helped Gaines and his colleagues reconsider the strategy. This kind of detailed conversation tends to be easier when people have the time, space, and sense of intimacy to get into the details together.

Communicate the purpose and norms. Once we brought together the host and visiting teams, we grounded ourselves in our shared purpose, the outcome data, and some shared commitments for how we wanted to show up for each other. One of those norms, which we adopted from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, “all teach, all learn,” sets the expectation that no one knows everything, and together we know a lot. We also invite participants to embrace norms about vulnerability, curiosity, getting into the details together, and sharing the air.

“Give people each other.” Joe McCannon, co-founder of the Billions Institute and previously with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, talks often about the importance of not just giving people tools for change, but also “giving people each other” — that is, cultivating space to connect as human beings and learners. We dedicate time and effort to building relationships and providing opportunities for dialogue throughout the process, from the launch to the debrief.

Don’t skip the teaching team component. The power of the live case is not just in the peer-to-peer learning that happens between the host team and visiting team, but in them coming together to spread effective practices to the rest of the network. To facilitate that process, CARPE uses a structure called spotlight sessions that we adapted from New Visions for Public Schools in which all network members interact with the teaching team around the promising strategies.

In the past, we had often defaulted to structures where everyone gets to share, often in small groups. This helped build a learning culture, but didn’t allow for the most promising ideas to rise to the top and spread quickly — in other words, it didn’t build the constellation we were aiming for.

Moreover, data we collect about the functioning of our network shows that, after we began conducting the spotlight sessions, members felt more connected to people in other teams, felt they had more voice in the direction of the network, and were implementing ideas from the sessions.

Learning in community

In our experience at CARPE, live cases are benefitting everyone involved — visiting teams, host teams, other network members, and ultimately, students.

For example, a college advisor from one visiting team explained that the experience gave her direct insight into opportunities that High Tech High International is providing its students. This enabled her school’s team to create similar programming that fits the school’s culture and student needs.

Another outcome is an increased sense of community through a shared purpose. Tom Gaines said that the live case reaffirmed that “we’re all in this journey together and we’re doing courageous, amazing work on behalf of kids who may need champions in their lives.”

At the end of the day, we know the real learning happens in community — for young people and adults — and that it is especially powerful when we have moments to get outside of our own bubbles. Connecting educators to each other through live cases and publicly sharing their learning is a systematic way of learning from variation, nurturing curiosity and humility, and spreading good ideas. All are essential in our collective work to design more equitable systems for students and each other.

Download pdf here.

“If you can learn what is working, and what is not…you can harness the power of the collective to understand 'what works for whom, under what conditions' and spread good ideas.” Stacey Caillier & Sofia Tannenhaus #TheLearningPro Share on XReferences

Avelar, L.S.R. & Johnson, R.S. (2019). Shattering inequities: Real-world wisdom for school and district leaders. Rowman & Littlefield.

Caillier, S. (Host). (2021, February 24). Don Berwick on improvement as learning. (Audio podcast). HTH Unboxed. hthunboxed.org/podcasts/213-don-berwick-on-improvement-as-learning/

Categories: Improvement science/networks, Learning communities, Reaching all students

Recent Issues

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES

June 2024

What does professional learning look like around the world? This issue...