FOCUS

Coaches support literacy across subject areas

By Dominique Bradley, Matthew Welch and Alicia Garcia

Categories: Coaching, Data, Improvement science/networksApril 2023

Literacy is a fundamental skill for students in every academic subject area and, most importantly, for navigating the world outside of school. Research has shown that students who struggle with reading are at greater risk of failure across subject areas and of dropping out of school (Heller & Greenleaf, 2007).

This is why the Long Beach Network for School Improvement focuses on building educators’ capacity to support student literacy skills in middle schools in Long Beach, California, with a particular focus on increasing the percentage of Black, Latinx, and low-income students who are on track for 8th-grade promotion and prepared to succeed in and after high school.

We support literacy development across subject areas at a time when students’ learning experiences are increasingly concentrated into subject-specific courses. Our change ideas are content agnostic, isolating literacy skills that students need to thrive not only in all classrooms, but also in their daily lives.

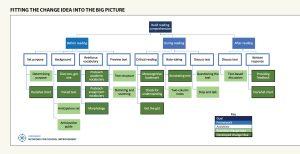

The figure above provides a map of the evidence-based change ideas our network uses and how they support literacy on a continuum of learning. It shows how we incorporate literacy strategies to support students before, during, and after reading. Examples of each include:

- Before reading: Ensure students understand lesson instructions and preteach vocabulary that will be used in a lesson;

- During reading: Engage with text through annotation and summarize the main points of a text; and

- After reading: Provide feedback to deepen student understanding of the text.

In this article, we introduce how our network operates, provide early findings of student success, share strategies that we found support cross-content implementation, and outline the challenges our network has faced and new ideas we are testing to address these challenges.

Coaching support

The network launched in fall 2020, just after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The network includes 97 middle school English language arts and social studies teachers and administrators from 10 schools in Long Beach Unified School District. A network hub, of which we (the authors of this article) are a part, supports these schools with professional learning, convening, and logistical support.

The network hub includes coaches who work with teachers in their schools. Those coaches are supported by subject matter experts in literacy and diversity, equity and inclusion, coaching, and research. The subject matter experts in literacy work with the coaches to identify literacy strategies that can support literacy across content areas in English language arts and history and that meet students’ needs within individual classrooms and What Works Clearinghouse standards for evidence-based practice. By using this approach, our network leverages expertise in the field and strategies that have been proven to work with similar students to improve literacy skills.

Network coaches support teachers to implement change ideas with a focus on the key teacher moves that affect student learning. At the same time, they support teachers to engage student voice, meet the needs of diverse learners, and respond to their particular classroom context and student composition. By identifying common gaps in students’ literacy skills, teacher teams in both English language arts and social studies can then move to identify a common change idea that will benefit students across classrooms, such as annotating for understanding, identifying the main idea, or using academic vocabulary.

Once school teams come to a commonly agreed-upon change idea, we use several coaching strategies to support cross-content work. Our hub team literacy experts help take the burden off teacher teams and network coaches by identifying core components of a strategy that must be present in implementation for a change idea to be carried out with enough fidelity for teacher efforts to be effective.

Coaches work with teacher teams to develop an implementation plan that specifies how all teachers will introduce the change idea in their classrooms, model it for students, and gradually release responsibility for that strategy to students over time. This coaching and planning process allows enough flexibility for individual teachers to adjust implementation for their specific classroom context.

Cross-content teacher teams work with coaches to introduce and model a “content-agnostic” literacy change idea in their classrooms. Gradually, the adults release responsibility for that strategy to students. #TheLearningPro Share on XCross-content comparison

Teachers identify measures of short-term proficiency and student engagement that the entire school team will use to assess whether their change idea and specific teacher moves are working to increase students’ comprehension and engagement. This identification of common measures helps cross-content area teams see how they can talk across the subject areas. Coaching conversations are key to helping the English language arts and history teachers come to this common understanding and common measurement strategy.

One example of this process is the development of a three-point rubric teachers use to assess several samples of student work from each teacher’s classroom. The common rubric allows for teams to measure students’ application of a strategy regardless of content area or type of assignment. In this way, teacher teams can talk about how well the strategy supported student learning broadly and whether that learning took place in social studies or English language arts assignments. They then work with their network coaches to determine what they will continue to do or what they will change.

Early findings

As we work with coaches and schools, the network hub members constantly ask: How do we know this process is working? Results on the short-term measures the school teams selected and used tell us that some strategies are working and that some are working better than others. But as a network, we want to know our efforts are producing overall, long-term success, so we also examine student achievement data.

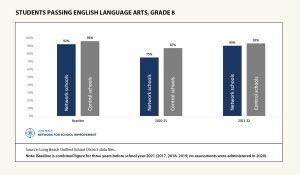

In the figure above, we look at the percentage of 8th-graders passing English language arts (that is, receiving a grade higher than an F), comparing cohorts of students attending network schools and other schools at several time points: just before the pandemic, after the launch of the network and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (school year 2020-21), and the following year (2021-22).

It is not surprising that many schools, including network schools, saw a drop in student academic outcomes after the onset of the pandemic, as represented in the middle bars of the figure. In the following year, however, English language arts passing rates improved, and network schools appeared to be rebounding from learning loss at slightly faster rates than comparison schools: Network schools’ English language arts passing rates were at only 2.4 percentage points below their prepandemic baseline, whereas comparison schools were 3.1 percentage points below their baseline.

Furthermore, Black and Latinx students in network schools are showing greater rebounds in literacy learning than students in other non-network schools in the district. While these initial results cannot be interpreted as causal, they do show promising trends related to the efforts of teachers in the network.

Navigating challenges

Given these promising results, we feel encouraged by our use of content-agnostic change ideas to reach our aim of improved literacy skills. However, these successes have not come without challenges.

Schools everywhere have experienced the challenges that came with the onset of COVID — remote learning, staff and student illness, intermittent lockdowns, general frustration with the new normal — and network schools are not immune to those stresses. Collecting data, developing implementation plans, and attending meetings to prepare to implement or modify a change idea can feel like an additional burden on already maxed-out teachers. Our network coaches and hub continue to puzzle over how to shift our approach so that implementing and testing change ideas is less of a burden and nests more seamlessly into the classroom.

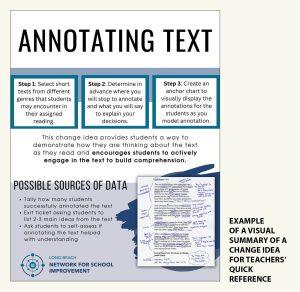

We removed some of the cognitive load of implementing change ideas by developing visual maps of our change ideas. For example, teachers can see the trajectory of learning to read for understanding and how the change ideas fit together in a constellation of strategies to support student learning. We have also developed slide decks and one-pagers (see the figure above) that simplify and visualize the core components of change ideas.

We also moved the burden of documenting data from teachers to the coaches, using preformatted spreadsheets, Google Jamboards, and note-catchers that can be completed during coaching meetings so that teachers don’t have to take additional actions outside of meetings. We are flexible in scheduling those coaching and network meetings, which sometimes means moving at a slower than ideal pace, but the trade-off is worth it to keep implementation going.

Many of these changes are new this school year, so we don’t know yet which changes or coaching strategies help teachers stay focused on doing the work of teaching while growing their own practice and deepening their pedagogy. While we continue to learn, it is our hope that the lessons from our network can provide valuable insights for other networks, professional learning leaders, and teachers as they navigate their own goals and challenges.

Download pdf here.

References

Heller, R. & Greenleaf, C. (2007). Literacy instruction in the content areas: Getting to the core of middle and high school improvement. Alliance for Excellent Education.

Categories: Coaching, Data, Improvement science/networks

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...