IDEAS

Equity-centered evaluation brings up emotions. That’s OK.

By Jennifer Ahn

Categories: Continuous improvement, Evaluation & impact, Facilitation, Reaching all studentsFebruary 2024

Strong emotions can surface when we evaluate our work, especially when we are deeply invested in it. Since professional learning is about shifting adult mindsets and behavior, it is work that frequently challenges assumptions, expectations, beliefs, instructional practices, and long-standing habits.

Complex and variable, the evaluation of its efficacy often involves strong feelings, especially when we are already trying hard to do what we think is right for our students, and especially when we think about the equity implications of our evaluation.

As a result, we often default to simplistic, compliance-driven modes of evaluation, simply measuring what people did. Compliance-driven modes of evaluation can create safety in their simplicity — we can avoid tricky topics and strong emotions if our evaluation is a checklist of tasks. Did people do what we asked them to do? Did they do it on time? Did they document what they did so we can track it? Easily measured, these forms of evaluation can lead educators to prioritize completion above quality and tasks over the people they hope to better serve — students and families.

But staying at that level means never digging in to understand the impact of our professional learning. This not only deprofessionalizes educators and ignores the complexity and humanistic aspects of the work. It also directs the focus of our improvement away from student groups who most stand to benefit from it.

The fear that our hard work has not led to the changes we want to see for marginalized students can lead us to shy away from examining it, which just undermines our goals. So how do we move beyond compliance-driven modes of evaluation to those that enable us to examine the equity implications of our work and have hard but important conversations about which students are ultimately being served by our professional learning? How can we create evaluative systems that center conversations about equity, especially when we are making sense of the results? And how can we help educators work through the strong emotions that emerge when examining the efficacy of their work?

To have meaningful and productive conversations about evaluation and data, educators must be equipped with effective practices and tools that allow them to recognize and work with strong emotions. And these opportunities must be a cyclical, embedded part of the evaluation process. That way, every time we evaluate professional learning, we ground our conversation in equity and data, centering the people we are most trying to support.

I explore these questions and ways to address them here using a case study from a large high school in the Bay Area of San Francisco, California, which I will call Bayview High to protect the school’s anonymity.

Case study: Bayview High

TACKLING RACIAL DISPROPORTIONALITIES

Since 2021, Bayview High staff have been tackling racial disproportionality in attendance, behavior, and academic outcomes, paying specific attention to their Black/African American students. During this time, I have worked with them and have seen their commitment to this goal manifest in their professional learning for the whole staff as well as in smaller professional learning communities (PLCs). This commitment threads throughout the restructuring of their walk-throughs, training in key initiatives, and the alignment of curriculum for their advisory period.

After two years of hard work, Bayview teachers and their school administrators were curious to evaluate the impact of their professional learning. They had spent the last two years planning, learning, and implementing. They were eager to understand if their efforts were leading to their desired equity outcomes.

A SOLID STARTING POINT

If Bayview teacher leaders and administrators were simply inventorying their action steps, their evaluation would reflect a glowing success. Collectively, they had done more in two years compared to similar schools, and their ability to generate staff buy-in and integrate new practices was remarkable.

While there are still a few reluctant colleagues, many staff can identify their schoolwide goals and feel invested in them. The school revamped walk-throughs to integrate peer-to-peer observation and shifted grading policies to raise the floor from zero to 50%; teachers identified focal students in every advisory period.

While taking stock of action steps is an important first step in any evaluation process, it can’t end there because it doesn’t assess impact. Questions exploring impact would include: Are peer-to-peer observations deepening awareness and aligning instruction? Did raising the grading floor decrease racial disproportionality in grades? Do focal students experience more belonging and come to school more often?

Fortunately, Bayview educators went beyond an inventory of actions and chose to evaluate their professional learning more deeply. They engaged in collaborative, sensemaking conversations grounded in data to evaluate how their professional learning was affecting student learning, with a closer look at their focal Black/African American students. Their conversations were richer than a summary of check-boxes.

A CHALLENGE: EQUITY TRAPS

Creating space to collectively look at data and make sense of it is essential in evaluation. Bayview teachers recognized this and created opportunities for discussion about the data. But a challenge quickly arose: Many educators fell into common equity traps.

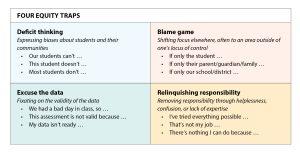

An equity trap is a distraction that enables us to shift thinking and personal responsibility away from understanding root causes of inequity. People fall into them for a variety of reasons, but usually it is because of the strong emotions that emerge when we try to have candid conversations about equity, including racial and gender justice.

During a conversation facilitated by administrators, Bayview’s staff noticed that, despite their best efforts, students’ progress report grades continued to reflect disproportionate outcomes. Black/African American students received more D and F grades than other groups.

Bayview administrators invited teachers to partner with them in a sensemaking conversation, hoping it would illuminate possible causes. Teachers were asked to pay specific attention to any Black/African American students on the list, guided by carefully crafted questions like:

- Are we doing what we said we were going to do?

- Did our actions make progress toward our desired change?

- Is there other data we could review that would give us more information?

- What are our key learnings and next steps?

Teachers could see that disproportionality was still present in the progress report data, but instead of raising genuine questions and honestly discussing root causes, many teachers fell into equity traps, such as discussing students’ lack of engagement or will.

These traps didn’t go unnoticed, but they often went undiscussed. One Bayview teacher leader told me that she noticed her colleagues engaging in one or more equity traps, but that she wasn’t sure how to discuss this in a safe way.

Another teacher leader wondered if colleagues deflected responsibility and fell into equity traps because they felt frustrated and at a loss for what to do. For instance, one teacher leader said that she worked really hard — calling students’ homes and pulling students aside for one-on-one conversations — and that she felt frustrated with the grading data because she didn’t know what else to do.

The Bayview teacher leaders identified strong feelings as reasons why they, and their colleagues, were falling into equity traps. These thinking patterns enabled them to deflect their defensiveness, shame, or fragility back onto the data or their students. Unfortunately, that also prevented them from being able to engage meaningfully in sensemaking conversations to evaluate their work honestly.

Based on my experience, the table on p. 53 outlines four equity traps to watch out for when looking at data to make sense of and evaluate impact.

NAMING EQUITY TRAPS

In some cases, the conversation led to discussion about the need for mindset shifts.

At one point in Bayview’s debrief conversation, a teacher leader said she was nice to those students on her D/F list, but they still didn’t attend. She felt she had tried and framed “niceness” as a best practice for increasing attendance, relinquishing her responsibility to do more.

Seeing this as the equity trap of relinquishing responsibility, a colleague responded, “Maybe we shouldn’t just be nice to them. Maybe we shouldn’t just be OK with them hardly coming to class. I feel like we’ve had this conversation every year, and we don’t act.”

While this comment created some tension, it also reflected progress. Earlier in the year, the Bayview staff participated in professional learning about the “culture of nice” and how it confuses courtesy with deep equity work.

The second teacher’s response references that work and weaves it into this conversation, bringing visibility to the equity trap. Perhaps the comment could have been shared more artfully, but we cannot always wait for feedback to come packaged according to our listening preferences. This comment marked a turning point that led the group toward deeper sensemaking and evaluation, and the evaluation process became more honest.

One teacher leader suggested that instead of making assumptions about this progress report data, they should discuss it with their focal students and adapt based on students’ responses. A school principal wondered aloud about “the difference between best practices and equity.”

As a group, they became curious and shifted their attention to learn more about their focal students. Able to handle this kind of honest talk, the group began looking at underlying assumptions as possible root causes.

AN EQUITY-CENTERED EVALUATION FRAMEWORK

When our evaluations do not equip and support educators to acknowledge equity traps, it is a missed opportunity. But this is easier said than done. How do you successfully discuss racial biases, which stir strong feelings?

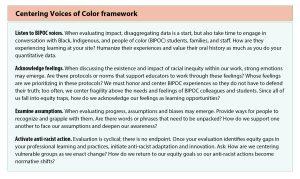

To understand how to do this and in service of racial equity, I started a BIPOC leaders network filled with teacher, school, and district leaders from across the Bay Area in spring 2021. This group seeks to center BIPOC educators’ experiences — and their thriving in schools — both as learners and as practitioners.

Listening to their experiences, wisdom, and feedback led my colleague Malia Tayabas-Kim and I to generate a framework that centers racial equity in professional learning. It includes the evaluation of professional learning and the sensemaking conversations that should accompany any evaluative process. See the elements of the framework above.

WORKING WITH EMOTIONS

After the debrief conversation at Bayview, I followed up with the administrators. They expressed concern and wondered if it had increased tension amongst the staff. I replied by saying that emotional tension also represents forward progress. Emotions are gifts that reveal our thinking, rich sources of learning that can catapult us to deepen our awareness of what we believe and value.

It takes bravery to acknowledge and work with our emotions in professional settings. By embracing the emotional load that comes with equity-centered evaluation, Bayview is better equipped to work toward transformational change. Administrators and teacher leaders are leading as partners, becoming learners who are exploring how to evaluate impact alongside their staff.

The Bayview High administrators, teacher leaders, and colleagues demonstrate a schoolwide commitment to racial justice by honestly evaluating their progress through equity-centered sensemaking. Collectively, the staff works to identify equity traps that may emerge.

In a move from assumption to inquiry, they have held regular learning partnership conversations with Black/ African American students and families. And, instead of doing one-off evaluative processes based on the completion of tasks, they routinely examine their professional learning outcomes so they can continuously adapt and improve.

Download pdf here.

Jennifer Ahn (je.ahn@northeastern.edu) is executive director of Lead by Learning.

Categories: Continuous improvement, Evaluation & impact, Facilitation, Reaching all students

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...