FOCUS

Language of learning: Content-rich texts build knowledge and skills

By Maryann Cucchiara

Categories: College- and career-ready standards, English learners, OutcomesApril 2019

Vol. 40 No. 2

Picture a classroom where two bright, inquisitive 8-year-old girls sit side by side. They both love soccer and math, and they both come from families who value education and have high expectations for their children’s futures.

Katie, who was born just down the road and has attended the school since prekindergarten, is one of the strongest students in the class, and her teachers often give her enrichment work and books to take home.

Maria Elena came to the school six months ago, after her family fled violence in El Salvador. She had no prior exposure to English and is working hard to learn how to speak with her teachers and classmates. But for the first time in her life, she feels disengaged and hopelessly behind her peers academically.

At first, Maria Elena looked forward to math class, expecting to find it easier to follow numbers than spoken language. But while her classmates learned about multiplication, she was pulled out for English lessons, vocabulary lessons, and reading instruction using texts designed specifically for decoding skills.

During these lessons, she could hear Katie and other classmates in the next room cheering as they played math games on the white board while she read sentences like, “The brown cat sat by the mat.”

Maria Elena frequently heard her mother talk about what a great education she was getting in the United States, but she was doubtful.

English learners like Maria Elena are capable of doing the same demanding work and developing the same complex skills as their peers who are native speakers. Indeed, recent education policies have specified that all students should meet common college- and career-ready standards.

Yet many schools use an outdated and ineffective approach to educating English learners, one that focuses on functional vocabulary and basic skills rather than the complex thinking and communication and literacy skills young people need to thrive in today’s world.

Too many students like Maria Elena have missed the chance to fulfill their potential because their teachers — many of them well-intentioned — don’t have the knowledge and capacity to serve them effectively.

Seeking to change that trend, beginning in the early 2000s, my colleague Lily Wong Fillmore and I developed an approach to teaching English learners that came to be called 3Ls. 3Ls stands for learning as the core instructional focus, with language and literacy integrated in seamless and purposeful ways that support core academic content rather than replacing it. Learning is the instructional goal; language and literacy are the vehicles to achieve it.

3Ls is a set of processes and tools educators can use to engage English learners — and all students — in college- and career-ready learning. We developed this work in the New York City and Boston public schools, but it has grown to reach other districts and populations.

Recently, we partnered with the Council of the Great City Schools, a national coalition of urban public schools, to create a program of online professional learning courses in using 3Ls. It is designed for educators serving high-needs English learners, but it is applicable to all students, not just English learners and not just those in urban settings. Professional learning for teachers and those who oversee and support them is central to the 3Ls approach.

FOCUS ON ACADEMIC LANGUAGE

The groundwork for 3Ls was laid in 2007, when, as director of research and development for English learners for New York City Public Schools, I set out to raise expectations and improve achievement among English learners in more than 350 public schools in the city.

These schools needed extra support because they had large numbers of students who had quickly learned the basic English skills needed to negotiate everyday life but lacked the reading and writing skills needed to meet grade-level expectations in English language arts and math.

Many of these students, like Maria Elena, had remained in beginner and intermediate level English classes for years, where the instructional model often consisted of drab, dumbed-down texts that were decontextualized and focused on everyday vocabulary and where students were rarely exposed to grade-appropriate content.

At that time, there was more confusion than clarity about how best to address the educational needs of English learners. Many educators hadn’t had much training on how to work with these students, and bilingual education wasn’t available in many places. Thus, the strategy was to teach English first and content later. In lieu of strategies tailored to English learners, schools used content materials meant for kindergarteners or 1st graders, no matter how old the English learner was.

Professional learning for teachers and those who oversee and support them is central to the 3Ls approach.

But Fillmore’s research on the instruction and experiences of these students raised a major red flag. She found that these students experienced stalled progress in language and literacy because of lack of exposure to complex and compelling text. Without a diet of rich and robust content input, English learners’ output continued to lag far behind their classmates.

Fillmore’s research laid out an alternative path in the form of “juicy texts” — texts that are authentic, rich, and engaging. These texts use academic language, which includes contextual, relevant background information that allows the reader to make sense of the text, even in an unfamiliar topic area.

These juicy texts offer clues about how this academic language works. Using these authentic and amplified texts, learners can advance in learning mature forms of academic language that go far beyond just vocabulary. (Download the supplemental content below to see sidebar on p. 35 for more information about specific instructional strategies that leverage the juicy texts.)

With this fortified input and appropriate support, Fillmore proposed, we would see a different progression — flashes of insight in the output of English learners and all students who needed a more robust and content-based approach to language and literacy (Fillmore & Fillmore, 2013).

BUILD EDUCATOR CAPACITY

Fillmore and I began collaborating to operationalize her research into concrete instructional practices and lesson and unit designs for teachers. What resulted was a learning process not only for educators, but for us about how to equip teachers with the knowledge and skills they need.

We knew that a prescriptive curriculum would not achieve our goals for teachers’ understanding or students’ learning. Instead, we focused on supporting teachers’ instructional vision so they could create lessons using texts, talk, and tasks to examine content, develop knowledge, and uncover learning, all while developing rich and complex academic language. Professional learning had to be at the heart of this approach.

In designing the professional learning, we began with three main instructional principles derived from research:

- Text, talk, and tasks should be cognitively demanding.

- Instruction should provide access, attention, and active engagement.

- Students learn from quality texts that are complex, compelling, concise, and connected.

It is not enough for a text to be complex. Students are more inclined to roll up their sleeves and tackle tough texts if the ideas in them are compelling. We looked for texts written by authors who are not only gifted writers, but also scholarly and passionate about their subjects. These texts create a sense of awe and wonder and invite inquiry and investigation.

Furthermore, all texts inside a unit of study should be connected to one another, so that those introduced later in the unit build on the ideas nested in the texts that came before. Concise yet complete excerpts are then chosen for close reading, during which teachers attend to the big ideas nested inside.

Rather than simply assigning rich texts, teachers need to use instructional moves that demystify academic language found in these complex texts. This attention to language involves rich and robust talk sessions between teacher and students and among student pairs or groups. They then actively engage students in differentiated tasks to provide pathways to learning at all levels of language and literacy.

LEARNING FROM LAB SITES

As we began putting these principles into a professional learning structure for the New York City schools, we quickly realized we needed a way to test and refine the strategies we were developing. We created 3Ls lab sites where we could work intensively and refine the strategies in a risk-free and nurturing atmosphere. At the lab sites, we videotaped kindergarten through high school classrooms and used those videos to observe practices we were developing, continue our research, and make changes as needed.

These lab sites gave us a snapshot of how 3Ls work can impact student achievement and teachers’ professional growth. The shift to compelling texts, talk, and tasks re-energized not only the student learners, but also the instructional staff as learners and researchers themselves. As one principal said, “I could see the change in the way our English language learners were participating in class, hands raised and on the edge of their seats.”

One of the main lessons for us from the lab sites was that professional learning for teachers needed to be scaffolded by support for leaders and systemic infrastructure. We saw that, for the 3Ls approach to take hold and thrive, it needed to be led in each school by informed and caring instructional leaders who supported teachers as they created lessons and units of study that were cognitively demanding and scaffolded to meet the needs of English learners and all learners who are striving in terms of academic language.

Furthermore, changing the paradigm from simplified to amplified texts, from a remedial approach to one that was grade-appropriate and accelerated, would require also educating and supporting superintendents, district staff, and school-based instructional leaders so that everyone would be working from a common understanding of best practices for English learners.

BROADEN THE REACH

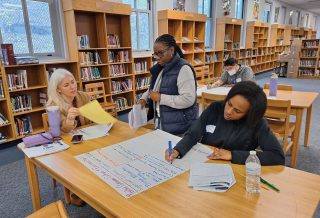

The approach that grew out of the lab sites is a three-year, three-pronged approach focused on juicy texts. It includes seminars for district and instructional leaders, teacher training, and laboratories of practice in which to observe, create, replicate, and assess these instructional practices.

To build on success in New York City, Boston, and elsewhere and make the approach accessible to a wider range of educators, we worked with the Council of the Great City Schools to develop a series of five online courses. Educators can complete the courses at their own pace and within a timeframe that works for them and their job responsibilities.

These are not one-shot courses, but a sustained, multipart program of courses that build on one another to transform teaching practices with practical tools, examples, and practice.

To start, all participants complete a foundations course to build a common understanding of the theory of action and a common vocabulary. Then they choose to follow either an English language arts/English language development pathway or a mathematics pathway. The pathways consist of five courses that walk participants through the essential elements of the 3Ls approach, including the research behind the approach, what the instructional approach should look like, and how to implement it.

Each course includes voices from instructional leaders, teachers, and students. The courses provide in-depth examples of teachers planning, implementing, and reflecting on the 3Ls approach. Coursework includes reading professional articles, reviewing sample lessons, and using implementation guides and templates for participant’s learning, applying, and reflecting stages.

POSITIVE CHANGES

As I look back and reflect on our work in New York City, Boston, and other large districts, I see many positive changes in schools. More districts are providing models of professional learning that begin with the firm belief that all students, including English learners, have the capacity for rich and robust instruction. Instructional leaders are making structural changes such as co-teaching to enable English learners to learn in classrooms with their native speaker peers.

Above all, English learners like Maria Elena are much less likely to be pulled out of mainstream classrooms for isolated skill instruction with simplified texts. Instead, they are more often sitting side by side with their native speaker classmates, joining in on compelling and complex social studies, science, math, and English language arts lessons and seizing opportunities to learn and grow in promising ways.

INSTRUCTIONAL SHIFTS IN THE 3LS APPROACH

- From isolated language skills to contextualized instruction.

- From everyday topics to content themes and academic language.

- From pull-out to push-in and co-teaching.

- From simplified to amplified.

References

Fillmore, L.W. & Fillmore, C.J. (2013). What does text complexity mean for English learners and language minority students? Stanford, CA: Stanford University School of Education.

McTighe, J. & Wiggins, G. (2013). Essential questions. Available at www.ascd.org/publications/books/109004/chapters/What-Makes-a-Question-Essential%A2.aspx.

Categories: College- and career-ready standards, English learners, Outcomes

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...