FOCUS

A districtwide path to acceleration starts with teacher teams

By Isobel Stevenson

Categories: Collaboration, Implementation, Learning systems/planning, Standards for Professional LearningJune 2023

Friday, March 13, 2020, was a professional learning day for many school districts in Connecticut. The timing was fortuitous because it gave educators a chance to make plans for the coming weeks. In the previous few days, we had learned that schools were going to be closed for a couple of weeks due to the rising threat from the pandemic that would come to be named COVID-19.

When it became clear that, in fact, schools were going to be closed for a lot longer, my colleagues and I at Partners for Educational Leadership went into overdrive figuring out how to support districts in their planning for online learning, and later, for the return in the fall.

When we realized remote learning was going to be with us for quite some time, we began researching and creating a framework and resources for districts to guide them in making decisions about instruction in an extremely challenging educational context — one that no one in our professional network had ever encountered before.

This article is the story of what we created and how Wilton Public Schools, a district in Connecticut, designed and facilitated professional learning for its teachers and leaders so that they might leverage academic acceleration in service of student learning. Wilton was recently ranked No. 1 on Connecticut’s Accountability Index, which is a combination of several metrics and prioritizes student growth over time. District leaders credit the implementation of their approach to accelerating learning with contributing greatly to their success.

Acceleration in the digital landscape

In summer 2020, amid confusion and lack of models to draw from, we began to come to grips with what to do in the new reality. After a good deal of research, we settled on acceleration as the foundational concept. We drew on the work of educators who made the case that remediation is ineffective (Rollins, 2014) and that students already spend too much of their school life doing work that is below grade level (Santelises & Dabrowski, 2015).

This statement, from TNTP (2020), sums it up best: “We found this approach of ‘meeting students where they are,’ though well-intentioned, practically guarantees they’ll lose more academic ground and reinforces misguided beliefs that some students can’t do grade-level work. The students stuck in this vicious cycle are disproportionately the most vulnerable: students of color, from low-income families, with special needs, or learning English.”

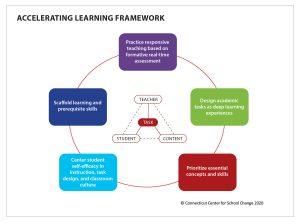

The work of acceleration is to stop worrying about what students have missed and focus instead on what they should be working on according to grade-level standards. With that as our organizing principle, and recognizing that there was little specific guidance available for educators, we set about creating a framework for districts to use in their planning that was both detailed and practical. The resulting model, the Accelerating Learning Framework, comprised our best thinking for organizing the collective efforts of educators to meet the needs of students in this highly unprecedented time.

During the design process, it came to light that this framework actually served several purposes. While it was first construed as a structure for planning instruction as a bridge between remote learning and a return to regular instruction, it became a guide for instructional practice during and after remote learning.

Components of the Accelerating Learning Framework

Prioritize essential concepts and skills. Students should be working on grade-level standards, no matter how much school they miss (Bakshi & Steiner, 2020; Resmovits, 2021). And while trying to teach everything in the curriculum for each grade level was not feasible given the real constraints of remote learning, districts could leverage the fact that curriculum in America is generally overstuffed and thoughtfully pare it down (Mehta & Peeples, 2020). This should be a district responsibility, not a task for individual teachers (Stevenson & Weiner, 2020).

Design academic tasks as deep learning experiences. During remote learning, educators struggled with radical shifts away from normal instructional routines and practices. We wanted to give them an uncomplicated way of sorting through all the activities they could be doing, and we settled on a single design question: What is the thinking that students are being asked to do? This encourages engagement in deep learning, with a focus on cognitive engagement, rather than on wide subject coverage.

Real-time, formative assessment ''is not about grading or determining the need for intervention. It means adjusting in the moment with the present students.'' #TheLearningPro #StudentSuccess #K12 Share on XPractice responsive teaching based on formative real-time assessment. This component is really about what Dylan Wiliam (2018) calls embedded formative assessment, but we have found that the term formative assessment can cause confusion, as many educators associate the term with testing and data teams. We define this as the teacher employing techniques to know where all students are in the learning process. Real-time assessment is not about grading or determining the need for intervention. It means adjusting in the moment with the present students. We use the phrase “even an exit slip is too late” to make that point.

Scaffold learning and prerequisite skills. Given that the lynchpin of acceleration is ensuring all students have access to grade-level content, we did not use the term differentiation. Differentiation has the connotation of “meeting students where they are,” which we explicitly seek to discourage. Instead, we encourage teachers to use scaffolding as a metaphorical platform under students, allowing them to access grade-level work.

This could be a concrete scaffold like a multiplication table or a word list, or just-in-time instruction of a concept students need to do a task. For example, if students have missed the instruction they need to work on a math problem involving division of multidigit numbers, the teacher can use what they know about multiplication and place value to create a ratio table they can use to solve the problem.

Center student self-efficacy. The impact on students during and after the pandemic lockdown is more than academic. At the very least, that disruption in daily life and instruction has affected their academic confidence. We know that we cannot take on the entire spectrum of social and emotional learning, but we do think it important to pay attention to building students’ belief that they can be successful if they put in effort.

We asked educators to be creative in helping students draw on their experiences of previous success to approach obstacles and frame goals so that the only way to fail was not to try. It might sound like this: “Mr. Malik told me you had a hard time in PE getting the beanbag through the hoop. He was very proud of you for persisting. Do you remember how you kept trying until you could do it, and how it felt when you realized that you could do it every time? This is the same thing! Keep trying, because that’s what’s most important. No one is expected to do it right away, so don’t worry. It may take you a long time, but persistence is a skill you already have, so use it.”

Wilton’s strategic approach

Wilton, Connecticut, is where we have seen the clearest implementation of and success with the framework. Wilton senior leaders made an early decision to adopt the Accelerating Learning Framework as the district strategy for managing and addressing unfinished learning.

They communicated to the entire community, starting with the school board and district administrators, that district resources would be aligned with acceleration as a strategy, including devoting time and resources toward professional learning for teachers.

Acceleration provided Wilton educators with a mindset for approaching unfinished learning. Wilton’s spring 2020 Measure of Academic Progress (MAP) assessment scores were much lower than in previous administrations, which was not surprising given the circumstances, but concerning nonetheless.

District leaders realized it was probable low scores could influence educators’ expectations of future student performance, so the district worked hard to replace the assumption that students were somehow “broken” or required remediation. Instead, they guided educators toward the concept of acceleration.

We and Wilton leaders recognized that professional learning would be key. In presenting the Accelerating Learning Framework to districts, my colleagues and I provided the best high-level, research-based, and engaging workshops we could create. However fabulous, it was still the opposite of job-embedded, ongoing, and experiential.

While the Wilton leaders used the materials we developed (such as slide decks, tools, recordings of our workshops, lists of books, articles, and resources), they were also aware that a turnkey approach has hard limits and that educators need opportunities to make meaning of the big ideas, time to plan, and support in working through questions and challenges.

In practice, this meant that district instructional leaders taught the framework, used it to structure agendas for and facilitation of meetings, and were relentless in making all gatherings, whether labeled professional learning or something else, as vehicles to teach about the framework. Perhaps not surprisingly, much of what the Wilton leaders spoke about could have been drawn straight from Learning Forward’s Standards for Professional Learning (Learning Forward, 2022).

A large part of the professional learning and planning took place via an existing structure in the school district: instructional effectiveness team meetings. These weekly meetings for teacher teams are attended by teachers, coaches, and building leaders and are the major vehicle for professional learning, continuous improvement, and joint planning for instruction.

District-level curriculum coordinators capitalized on this structure to support teachers by providing them with plans and timelines that removed some of the uncertainty in a very uncertain time; ways of strategizing around lost instructional time drawn from the Accelerating Learning Framework (prioritizing foundational skills, staying on grade level, scaffolding as the district’s approach to differentiation, and so on); and support for how to enact these principles by having coaches and coordinators work hand in hand with teachers to enact these principles through the lesson planning process.

In addition, Wilton’s central office staff set the direction and made teachers’ lives easier by shouldering the work of prioritizing the curriculum based on student-level data. They created a spreadsheet to track student data at a granular level. The spreadsheet identifies foundational skills in literacy and mathematics; tracks them across overlapping grade bands (K-1, 1-2, 2-3, etc.) so that teachers can see learning progression; identifies the instructional units where the skills appear; and captures where students are with mastering the skill.

The best professional learning ''...happens when curriculum experts, instructional coaches, and teachers work together to meet actual challenges in engaging students in learning, even when the conditions are far from ideal.''… Share on XWith teachers not having to spend time prioritizing curriculum, they were able to design instruction collaboratively — an example of job-embedded professional learning. Wilton central office leaders are clear that the best professional learning isn’t always labeled as such. It happens when curriculum experts, instructional coaches, and teachers work together to meet actual challenges in engaging students in learning, even when the conditions are far from ideal.

Wilton adopted the Accelerating Learning Framework at several levels: as a set of guidelines for instructional practice, a framework for building capacity in teachers, a focus for instructional leadership in coaches, principals, and central office leaders, and the district’s overall strategy for improvement. It became a vehicle for coherence across the district, and none of that would have been possible without a comprehensive approach to collaborative planning.

As a result, the district is not focused on remediation but on ensuring that students have access to grade-level content. Teachers have permission and support to prioritize those parts of the curriculum that are foundational to success in higher grade levels. And there is increased priority on student agency — through goal setting, for example — and self-efficacy because when students believe that they can be successful, they experience more success.

Acceleration moving forward

Wilton and the other successful districts we have worked with not only leveraged the Accelerating Learning Framework to cope with the acute phase of the pandemic, but are planning to use it as a blueprint moving forward. For Wilton, the backbone of the district’s strategy from now on is a focus on engaging teachers in ongoing professional learning so they have the capacity to support students’ success in doing grade-level work.

As before the pandemic, the instructional effectiveness teams continue to meet, and each school is engaged in continuous improvement around an instructional focus. Wilton started with a blueprint for unfinished learning that identified where the unfinished learning “lived” in each grade level.

From there, the district emphasized the key understandings from the Accelerating Learning Framework: scaffold grade-level learning over remediation and develop responsive lesson planning to grow learners who could achieve grade-level expectations. Later, it deepened the learning with task design and scaffolding, and it continues to deepen and refine these two practices.

Sometimes it takes a crisis to help us distill what really matters. In my organization, we learned that, while we have always advocated for the individual pieces of the Accelerating Learning Framework, we had not pushed hard enough for the integrated whole. Once they were treated as such, it became both easier and more potent to engage teachers in professional learning that paid off in service of students.

As with so many practices, what makes the difference is vision, clarity, and consistency in implementation. That is never easy to accomplish, especially in a time of enormous uncertainty and unpredictability. But it could not be realized without a coordinated effort among central office, building leaders, and coaches to provide teachers with everything from high-level concepts, frameworks, and timelines to partnership in planning for unprecedented instructional conditions.

The work of Wilton during the pandemic gave new meaning to the phrase job-embedded professional learning, as all the educators in the district worked to learn what they needed to know to engage students that day. Wilton, of course, is not unique in this. What teachers across the country accomplished in service of their students during the pandemic has been a credit to the profession.

Download pdf here.

References

Bakshi, S. & Steiner, D. (2020, June 26). Acceleration, not remediation: Lessons from the field. The Thomas B. Fordham Institute. fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/acceleration-not-remediation-lessons-field

Learning Forward. (2022). Standards for Professional Learning. Author.

Mehta, J. & Peeples, S. (2020, June 25). Marie Kondo the curriculum. Shanker Institute. www.shankerinstitute.org/blog/marie-kondo-curriculum

Resmovits, J. (2021, January 18). How a diverse school district is using a strategy usually reserved for ‘gifted’ students to boost everyone. The Seattle Times. www.seattletimes.com/education-lab/how-highline-is-trying-to-avoid-learning-loss-by-boosting-students-ahead/

Rollins, S.P. (2014). Learning in the fast lane: 8 ways to put ALL students on the road to academic success. ASCD.

Santelises, S. & Dabrowski, J. (2015). Checking in: Do classroom assignments reflect today’s higher standards? The Education Trust. edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/CheckingIn_TheEducationTrust_Sept20152.pdf

Stevenson, I. & Weiner, J.M. (2020). The strategy playbook for educational leaders: Principles and processes. Routledge.

TNTP. (2020, April). Learning acceleration guide: Planning for acceleration in the 2020- 2021 school year. Author. tntp.org/assets/covid-19-toolkit-resources/TNTP_Learning_Acceleration_Guide.pdf

Wiliam, D. (2018). Embedded formative assessment (2nd ed.). Solution Tree.

Isobel Stevenson is director of organizational learning (istevenson@partnersforel.org) at Partners for Educational Leadership.

Categories: Collaboration, Implementation, Learning systems/planning, Standards for Professional Learning

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...