FOCUS

Flip the script on change

By Thomas R. Guskey

Categories: Change management, Evaluation & impact, OutcomesApril 2020

Vol 41, No. 2

Teaching is a demanding profession. Teachers dedicate themselves to having all their students learn well and take pride in seeing their students’ learning success. But what happens when students don’t succeed? How do teachers explain students not learning well or not reaching expected levels of achievement?

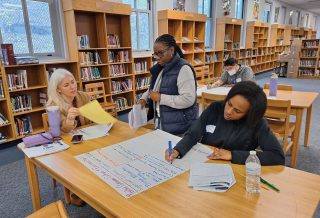

''Experience shapes teachers’ attitudes and beliefs (not the other way around).'' @tguskey #LearnFwdTLP Share on XIn a recent research column for The Learning Professional, Elizabeth Foster (2019) reviewed a study that considered this issue. Margaret Evans and her colleagues (Evans, Teasdale, Gannon-Slater, La Londe, Crenshaw, Greene, & Schwandt, 2019) investigated teachers’ perceptions of student achievement data. Their study focused on the work of six grade-level teams of teachers (grades 3-5) who met biweekly to discuss various examples of student performance data.

What Foster found surprising was that teachers attributed students’ performance to their instruction only 15% of the time. Far more frequently, they connected results to student characteristics, particularly students’ behavior, effort, or background.

We’ve long known that individual student characteristics, family background, and neighborhood experiences contribute to students’ performance in school (Stewart, 2008). We also know that many of these student characteristics lie outside teachers’ control. Nevertheless, significant research also shows that, among school-related factors affecting achievement, teachers matter the most. Studies estimate that teachers have two to three times the impact of any other school factor, including services, facilities, and even leadership (Hattie, 2003; Rand Education, 2012).

''Studies estimate that teachers have two to three times the impact of any other school factor, including services, facilities, and even leadership.'' #LearnFwdTLP Share on XThe results of the Evans et al. (2019) study prompt two important questions for those who design and lead professional learning. First, how did these teachers come to their beliefs? Specifically, why do they see their instructional practices as having so little influence on student learning? And second, how can we change this? If teachers viewing evidence of student learning see their impact as so modest, the prospects for improvement are pretty dismal. How can we help teachers recognize that what they do matters and they can have an important impact on how well students learn?

What Doesn’t Work?

Many education leaders, writers, and consultants think the best way to change teachers’ beliefs is through logic, reason, and philosophical arguments. They approach change by presenting logical and carefully reasoned points that illustrate discrepancies between current evidence and teachers’ perspectives. They believe that when teachers see these logical and philosophical inconsistencies, they will recognize the errors in their thinking and commit to change.

In essence, they are trying to create what psychologists refer to as “cognitive dissonance,” a concept originated over a half century ago by psychologist Leon Festinger (1957). Cognitive dissonance occurs when individuals are confronted with new information or situations that contradict their current beliefs, ideas, or values.

To deal with the psychological discomfort of this dissonance, individuals do one of three things. They can avoid the contradictory information or situations that prompt the dissonance; alter their understanding of the new information or situations to reduce the dissonance; or revise their beliefs, ideas, or values to align with the new information or situation.

In other words, they can ignore the new, change the new to fit their view, or change their view to align with the new. The most difficult of these to accomplish is the third: revising personal beliefs, ideas, or values.

The leaders, writers, and consultants seeking to initiate reforms generally try to create cognitive dissonance in one of three ways: confrontation, mental manipulation, or emotional appeal.

Those who use confrontation typically begin by describing the beliefs or practices they want teachers to change as traditional. They initially portray the traditional as innocent, innocuous, and generally accepted. But they quickly turn the tables and label demeaning, student-unfriendly practices as traditional, then present the practices they advocate as the most effective path to reform.

Those who use mental manipulation generally construct arguments to show educators the wrongness of their thinking, the illogic of their assumptions, or the inappropriateness of their beliefs. They attempt to persuade through mental entanglement, convincing educators that their beliefs cannot be justified through reason or logic.

Those who use emotional appeal try to instill in educators a highly emotional response to their ideas and opinions. They tell heart-wrenching stories of the hardships students suffer and the alleged devastating effects of the policies or practices they want educators to change. They stress that continuing these policies and practices will have dire consequences for students and, as a result, present change as a moral imperative.

Unfortunately, these techniques rarely produce significant and enduring change. As renowned psychologist Edward de Bono noted, “Logic will never change emotion or perception” (quoted in Balakrishnan, 2007). Emotions, attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs are not formed intellectually, and they typically are not defended rationally. Instead, they are driven by what people have previously known and experienced.

What Does Work?

Ensuring positive and sustained change requires a different view of the change process, one that challenges the commonly assumed impetus for change.

Educators generally agree that improvement efforts are designed to bring about change in three major areas (Learning Forward, 2011): teachers’ attitudes and beliefs, teachers’ classroom practices, and student learning outcomes, including achievement, engagement, and attitude. What educators don’t agree on is the order of these changes.

As described earlier, many professional learning efforts are based on the assumption that change in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs will lead to changes in their classroom practices, which, in turn, will result in improved student learning. However, modern investigations of teacher change show that this assumption is generally inaccurate, especially for experienced educators (Putnam & Borko, 2000).

Instead, significant changes in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs take place only after positive change in student learning is evident. These improvements in student learning result from specific changes teachers make in their classroom practices — e.g. new materials or curriculum, new classroom policies and practices (Guskey, 1986).

As the model of teacher change on p. 19 illustrates, the critical point is that professional learning alone rarely yields significant change in teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, or dispositions. These attributes change only when teachers have clear evidence of improvement in students’ learning outcomes (Guskey, 1989, 2002).

Experience shapes teachers’ attitudes and beliefs. Teachers retain and repeat practices that work, whether in motivating students, managing student learning, or helping students attain desired learning outcomes. They generally abandon practices that don’t work or fail to yield any tangible evidence of improvement. Therefore, the endurance of any change in classroom practices and procedures relies on demonstrable results in student outcomes.

Implications of the Model

This alternative change model yields several powerful implications for those who design and lead professional learning.

1. Efforts to change attitudes and beliefs directly rarely succeed.

Leaders who set out to change teachers’ attitudes and beliefs directly are mostly doomed to fail. Modest change may be possible and definitely should be sought. When presented with new ideas and supporting evidence on new approaches to instruction, for example, teachers’ attitudes may be moved from cynical to skeptical and they may consider new points of view. But confidence in a new approach and commitment to it are rare up front. The best that can be hoped for is a tentative, “I’m not sure, but I’ll give it a try.”

The key to success rests in changing their experience. The film Remember the Titans provides an excellent example of how changing experience can lead to changed attitudes. Based on a true story, the film portrays African American coach Herman Boone’s efforts to integrate a high school football team in Alexandria, Virginia, in the early 1970s. Changing the experience of these young athletes transformed their attitudes and beliefs. Similarly, meaningful change in teachers’ experience is key to significant change in their attitudes and beliefs.

2. Change is a gradual and difficult process, especially for teachers.

Becoming proficient at something new and finding meaning in a new way of doing things requires time and effort. Any change that holds great promise for increasing teachers’ effectiveness and enhancing student outcomes will likely require extra work, especially when beginning. This can significantly add to teachers’ workload.

In addition, change can feel threatening and usually brings a certain amount of anxiety. Trying something new means risking failure, which runs counter to most teachers’ strong commitment to ensuring every student learns. Therefore, even when presented with evidence from carefully designed experimental studies, teachers do not easily alter or discard the practices they have developed and refined in their classrooms (Hargreaves, 2005).

It is also important to recognize that every school will not implement reforms identically. Reforms based on assumptions of uniformity in the educational system repeatedly fail (Elmore, 1997). Any change must strike an appropriate balance between program fidelity and contextual conditions.

Researchers point to the need for “mutual adaptation” (McLaughlin, 1976): Individuals must adapt to implement the new policies and practices, but the innovation also must be adapted to fit the unique characteristics of the context.

Too much change in either direction can mean disaster. If the innovation requires too much adaptation from individuals, implementation is likely to be mechanical and ineffective. But too much adaptation of the innovation may result in the loss of elements essential to program impact. Successful implementation requires a critical balance between the workload requirements of teachers and vital dimensions of innovation fidelity.

3. Feedback on results is essential.

For new practices to be sustained and changes to endure, teachers need regular feedback about the effects of these efforts. Success is reinforcing. People tend to repeat the actions that cause it and decrease or halt actions that don’t. This is especially true of teachers, whose primary psychological rewards come from feeling certain about their capacity to affect student growth and development (Huberman, 1992). Professional learning initiatives must include procedures that offer teachers frequent and specific feedback on results.

However, that feedback must be based on evidence that teachers trust and find meaningful. Equally important, it must be evidence that comes rather quickly (Guskey, 2007). With instructional reforms, for example, it would be helpful for teachers to see not only improved classroom assessment results, but also students more engaged in class activities, more willing to participate in class, or developing greater confidence in themselves as learners. Teachers won’t wait two or three months to see if new strategies or practices work. They want to see evidence of change in their students within a few weeks or a month at most.

4. Change requires continued follow-up, support, and pressure.

If change in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs occurred primarily before the implementation of new practices or innovations, the quality of the initial professional learning would be of utmost importance. But because evidence of improved student outcomes is necessary for change, it is the continuous follow-up that teachers receive that is most crucial.

Support should be coupled with pressure. Support allows those engaged in the difficult process of implementation to tolerate the anxiety of occasional setbacks. Pressure is often necessary to initiate change among those whose self-impetus for change is not great (Corcoran, Fuhman, & Belcher, 2001) and ensure persistence in the challenging tasks intrinsic to all improvement efforts.

Of all aspects of professional learning, follow-up is perhaps the most neglected. Yet to be successful, professional learning must be seen as a process, not an event (Learning Forward, 2011). Learning to be proficient at something new or finding meaning in a new way of doing things is difficult and sometimes painful. Teachers need support to ensure that improvement is seen as a continuous and ongoing endeavor.

Altering Teachers’ Experience

Those who design and lead professional learning must ensure that teachers implement practices that have strong research support and yield evidence of success that teachers can experience firsthand. Examining evidence on students’ performance is vital to improving educational outcomes.

But for these examinations to be effective, teachers must believe their actions influence those outcomes. Implementing innovations that lack supporting research evidence and fail to yield positive results causes teachers to believe their actions don’t matter (Guskey, 2018). This diminishes teachers’ enthusiasm toward professional learning and challenges their belief in their own effectiveness.

Because experience shapes teachers’ attitudes and beliefs, change efforts must focus on altering teachers’ experience. They must help teachers gather that evidence to verify positive results when they occur and make necessary revisions when they don’t.

Change is a complex process, but it’s not haphazard. Careful attention to the order of change events described in the model presented here will not only facilitate change but also ensure its endurance.

References

Balakrishnan, A. (2007, April 23). Edward de Bono: ‘Iraq? They just need to think it through.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2007/apr/24/highereducationprofile.academicexperts

Corcoran, T., Fuhman, S.H., & Belcher, C.L. (2001). The district role in instructional improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 83(1), 78-84.

Elmore, R.F. (1997). The paradox of innovation in education: Cycles of reform and the resilience of teaching. In A.A. Altshuler & R.D. Behn (Eds.), Innovation in American government: Challenges, opportunities, and dilemmas (pp. 246-273). Brookings Institute Press.

Evans, M., Teasdale, R.M., Gannon-Slater, N., La Londe, P.G., Crenshaw, H.L., Greene, J.C., & Schwandt, T.A. (2019). How did that happen? Teachers’ explanations for low test scores. Teachers College Record, 121(2), 1-40.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Foster, E. (2019). Study examines teachers’ perceptions of student achievement data. The Learning Professional, 40(3), 20-23.

Guskey, T.R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educational Researcher, 15(5), 5-12.

Guskey, T.R. (1989). Attitude and perceptual change in teachers. International Journal of Educational Research, 13(4), 439-453.

Guskey, T.R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8(3/4), 381-391.

Guskey, T.R. (2007). Multiple sources of evidence: An analysis of stakeholders’ perceptions of various indicators of student learning. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 26(1), 19-27.

Guskey, T.R. (2018, September 9). How can we improve professional inquiry? Education Week Blog. https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/finding_common_ground/2018/09/how_can_we_improve_professional_inquiry.html

Hargreaves, A. (2005). Educational change takes ages: Life, career, and generational factors in teachers’ emotional responses to educational change. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 967-983.

Hattie, J. (2003, October). Teachers make a difference: What is the research evidence? Paper presented at the ACER Research Conference, Melbourne, Australia. https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2003/4

Huberman, M. (1992). Teacher development and instructional mastery. In A. Hargreaves & M.G. Fullan (Eds.), Understanding teacher development (pp. 122-142). Teachers College Press.

Learning Forward (2011). Standards for Professional Learning. Learning Forward.

McLaughlin, M.W. (1976). Implementation as mutual adaptation: Changes in classroom organization. Teachers College Record, 77(3), 339-351.

Putnam, R.T. & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4-15.

Rand Education. (2012). Teachers matter: Understanding teachers’ impact on student achievement. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4312.html

Stewart, E.B. (2008). School structural characteristics, student effort, peer associations, and parental involvement: The influence of school- and individual-level factors on academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 40(2), 179-204.

Thomas R. Guskey, PhD, is Professor Emeritus in the College of Education, University of Kentucky. He is a longtime member of Learning Forward, best known for his work on teacher change and on planning, implementing, and evaluating effective professional learning. Contact him by email at guskey@uky.edu, on X at @tguskey, or at www.tguskey.com.

Categories: Change management, Evaluation & impact, Outcomes

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...