FOCUS

Tackling instructional mismatch

Targeted, intentional learning can build leaders' content knowledge

By Sarah Quebec Fuentes and Jo Beth Jimerson

Categories: Leadership, Learning designs, School leadershipOctober 2019

Vol. 40, No. 5

At the heart of effective school leadership are robust instructional leadership practices. An emphasis on instructional leadership is neither new nor simple.

We’ve spent the last several years talking with teachers, school leaders, and content experts about how they engage in instructional leadership and the challenges with which they struggle. One takeaway from this work is that much, if not most, of the time, leaders are engaging in their work within a context of instructional mismatch.

Most leaders end up working either with teachers in grade levels they did not teach (e.g. a secondary teacher who becomes an elementary school administrator) or with teachers in unfamiliar content areas (e.g. a former mathematics teacher who supervises social studies and English language arts teachers).

This was the case for one of our research participants, whom we will call Danelle Richards. (Participants’ real names are confidential, in keeping with our research project’s protocols.) Richards, an elementary principal (and former secondary science teacher), told us she felt very vulnerable and unqualified when she worked with teachers on reading instruction — an area of double mismatch (grade level and content area).

Particularly in her early years, she was “very hesitant to provide feedback for subject areas” where mismatch was prominent. Other leaders we’ve worked with have used the words uncomfortable, unqualified, hesitant, vulnerable, intimidated, and anxious to describe how they feel when called on to work with teachers in areas of mismatch.

In such cases, leaders may have difficulties participating in the kinds of rich dialogue and feedback that could lead to substantial improvements in teacher practice and student learning.

The challenge for leaders wanting to bridge this mismatch gap and maximize impact as an instructional leader is to engage in what we call targeted and intentional instructional learnership. Instructional learnership means building knowledge about content-specific teaching practices in a way that is meaningful, ongoing, transparent, and draws on the resources and expertise of colleagues.

In this #LearnFwdTLP article, @squebecfuentes & @JBJimer help educators understand that targeted, intentional learning can build leaders' content knowledge. But what is instructional learnership? Share on XA focus on intentional and in-depth instructional learnership is not yet widespread, perhaps because of the complexities involved with school leadership and competing demands. But we believe it is a critical element in crafting and supporting effective learning opportunities for faculty, staff, and students, and we have created a structure to help school leaders build it.

Leadership content knowledge

Although leaders with whom we’ve worked often noted mismatch as a challenge, few talk about intentional efforts to seek learning opportunities in these areas of mismatch. Some stress the importance of the principal as lead learner but describe their learning as focused primarily on general leadership strategies.

Of course, leaders cannot be expected to know everything about content-area instruction, but all leaders can know something about various content areas. To build this knowledge, leaders can benefit from the concept of leadership content knowledge (Stein & Nelson, 2003).

''Leaders cannot be expected to know everything about content-area instruction, but all leaders can know something about various content areas.'' #LearnFwdTLP #SchoolLeadership Share on XIn contrast to pedagogical content knowledge, which is the unique knowledge base that exists for each subject area at the intersection of content and pedagogy (Shulman, 1986, 1987), leadership content knowledge focuses on the big, overarching ideas in a discipline. For instance, a mathematics teacher’s pedagogical content knowledge should include a depth and breadth of understanding across the range of effective teaching practices specific to mathematics.

In contrast, a principal’s leadership content knowledge involves familiarity with several effective mathematics teaching practices, such as the incorporation of high-level tasks, purposeful connections across representations, and the facilitation of discourse (NCTM, 2014).

When working in an area of mismatch, leaders often opt to focus on content-neutral or “crossover” practices. For instance, middle school assistant principal Jade Turner (a pseudonym), describing her work in an area of mismatch, confided, “I am kind of along for the ride with the students as opposed to looking through the lens of how [teachers] can refine their specific practices. … [I ask], ‘Have you tried refining your essential question? Have you tried using hands-on activities? Have you tried students collaborating more?’ They’re just basic strategies.” This fits with what many school leaders tell us: “Good teaching is good teaching.”

Focusing on global practices, like essential questions and formative assessment strategies, is indeed an important component of instructional leadership. However, as Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, and Wiliam (2004) noted in work on formative assessment, “generic strategies could only go so far” (p. 16). They go on to explain:

“Choosing a good question requires a detailed knowledge of the subject. … Furthermore, such pedagogical content knowledge is essential in interpreting responses. That is, what students say will contain clues to aspects of their thinking that may require attention, but picking up on these clues requires a thorough knowledge of common difficulties in learning the subject” (Black et al., 2004, pp. 16-17).

For example, Milo Collins, a secondary mathematics teacher, talked about the conversations he enjoyed with a math-savvy administrator, noting, “[asking] ‘How do you build a child’s understanding of functions?’ … is so much more meaningful than ‘Did I do a thumbs-up seven minutes ago?’ ”

Attention to crossover practices can be practical, but a blending of crossover practices with leadership content knowledge, as Collins’ situation illustrates, provides a platform for rich dialogues between teachers and school leaders.

Powering up feedback

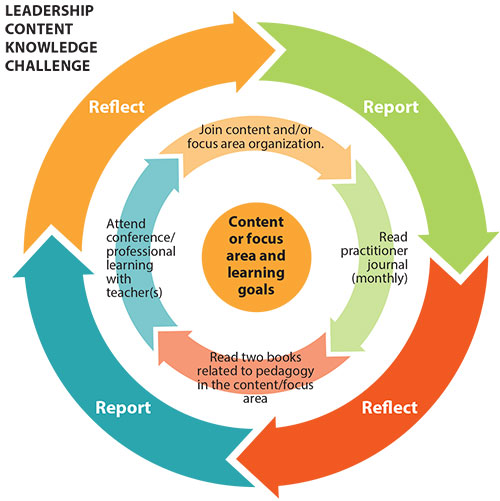

To help leaders build leadership content knowledge and overcome instructional mismatch, we propose the Leadership Content Knowledge Challenge. This challenge invites leaders to choose one area of mismatch (e.g. mathematics, arts, or bilingual education) and learn — deeply and publicly — about instruction in that area over the next year.

Leaders begin the challenge by talking with instructional experts (e.g. instructional coaches/specialists and teacher leaders on their campus or elsewhere) to identify key organizations, readings, conferences, and resources considered central to the discipline and reflective of effective practices.

They then set learning goals in consultation with these experts, align key activities and readings (see the figure to the right), and share their challenge plan with faculty and staff. Individually or in concert with a professional learning network, leaders enact the plan, embedding regular reflection and opportunities to report out learning throughout the year.

To help leaders build leadership content knowledge and overcome instructional mismatch, @squebecfuentes & @JBJimer propose the Leadership Content Knowledge Challenge. #LearnFwdTLP Learn more: Share on X

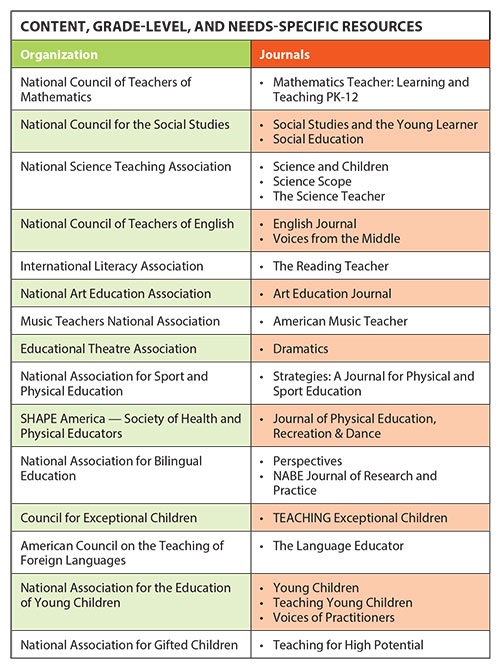

As an example, suppose a former high school geography teacher now serving as a middle school principal chooses to build capacity in mathematics education. After visiting with a district mathematics coach and developing learning goals, she joins the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics and reads Mathematics Teacher: Learning and Teaching PK-12, a journal that comes with the membership, throughout the year.

She also commits to reading two books recommended by the mathematics coach — Principles to Actions: Ensuring Mathematical Success for All (NCTM, 2014) and Mathematical Mindsets (Boaler, 2016). Throughout the year, she is intentional about spending time in the classrooms of mathematics teacher leaders to learn more about their pedagogical choices.

Upon recommendation from the mathematics coach, the geography teacher-turned-principal registers for two days of professional learning she will attend with grade-level mathematics teacher leaders, through which she receives a copy of Building a Math-Positive Culture (Seeley, 2016). She presents her learning plan to her faculty early in the fall semester.

She also keeps a reflective journal, noting the ways in which her learning about mathematics instruction intersects with her walk-throughs and observations at the campus, and reports on her progress to the faculty several times during the year.

She realizes that, counter to assumptions that learning from and with teachers may make leaders appear unqualified, making her learning transparent actually builds credibility and establishes relationships built on trust and mutual development (Lochmiller, 2019).

The table below lists examples of content- and program-specific organizations and associated journals.

Brokering connections

Leaders who undertake the challenge can not only enhance their ability to layer rich instructional feedback atop crossover (or content-neutral) practices, but also become more effective brokers of information and resources to support teacher growth.

School leaders who have leadership content knowledge are more likely to detect when lively teaching may mask the absence of rigorous instruction (see Bauml, 2016).

They are able to spot teachers who need additional supports, but who may not recognize that need on their own. And being able to recognize the needs of exemplary teachers — via observation or dialogue — is similarly important.

Cycles of instructional learnership

Ideally, the Leadership Content Knowledge Challenge will reap benefits that lead to a second cycle, in a new content area, and on to a third, and beyond. Leaders need not limit themselves to content areas subject to state or federal testing requirements.

Instruction in the arts and health/wellness, as well as in special program areas (e.g. special education, gifted education, bilingual programming) should not be overlooked. In this way, instructional mismatch becomes an on-ramp for rich learning across disciplines and an opportunity to engage as lead and co-learner with an eye toward long-term instructional improvement.

Want to hear from the authors and other educators about this topic? Check out the recap of a Twiter chat that was based on this article.

References

Bauml, M. (2016). Is it cute or does it count? Learning to teach for meaningful social studies in elementary grades. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 40(1), 55-69.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Working inside the black box: Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 86(1), 8-21.

Boaler, J. (2016). Mathematical mindsets. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lochmiller, C.R. (2019). Credibility in instructional supervision: A catalyst for differentiated supervision. In M.I. Derrington and J. Brandon (Eds.), Differentiated Teacher Evaluation and Professional Learning (pp. 83-105). Palgrave Studies on Leadership and Learning in Teacher Education. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2014). Principles to actions: Ensuring mathematical success for all. Reston, VA: Author.

Seeley, C.S. (2016). Building a math-positive culture: How to support great math teaching in your school. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15, 4-14.

Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-22.

Stein, M.K. & Nelson, B.S. (2003). Leadership content knowledge. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(4), 423-44.

Categories: Leadership, Learning designs, School leadership

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...