FOCUS

7 reasons to evaluate professional learning

By Joellen Killion

Categories: Continuous improvement, Data, Evaluation & impact, ImplementationFebruary 2024

Each year, educators engage in hours of professional learning to enhance their practice. Those hours are limited, both by contract and the imperative of keeping teachers in classrooms as much as possible. It is essential that this professional learning time is well-spent and pays dividends toward the goal of all public education: ensuring that each student succeeds. Evaluation is fundamental for assessing the quality, effectiveness, and impact of professional learning. It provides data for planning and strengthening educators’ learning and, ultimately, explaining and justifying school systems’ investments in it.

When educators neglect to collect and analyze data about the effects of professional learning, they tend to default to some common fallacies about it:

- When educators attend professional learning, students automatically benefit.

- If educators report that professional learning was beneficial, they will change their practice and students will benefit.

- Spending more on professional learning guarantees that educators and students will benefit.

- When professional learning focuses on evidence-based practices, student success automatically increases.

Evaluation is 🔑 key to effective professional learning. Joellen Killion explains how assessing quality, impact, and social justice aspects all ensure educators and students benefit fully. #Education #TheLearningPro #HQPL @jpkillion Share on X

These assumptions have limited educators’ efforts to collect data and measure the relationship between professional learning and student success. In many cases, there is, in fact, a positive relationship between professional learning and improvements for educators and students. But without evaluation, we don’t have an abundance of evidence to support the claim. This means that policymakers, parents, teachers, and others may question the value of professional learning that is making a difference. Just as concerning, they may rely on learning that isn’t as effective as it can be.

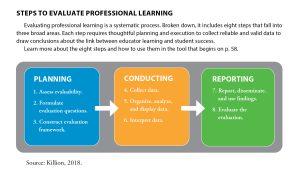

To address those gaps, professional learning leaders engage in evaluation. Evaluating professional learning is a systematic process of identifying questions, collecting and analyzing data, and formulating conclusions or generalizations about the link between educator learning and student success to plan next actions. (See sidebar on p. 27 and the tool on p. 58 to read about the eight steps of successful professional learning evaluation.)

Professional learning evaluation is a particular type of research, with certain unique considerations that have been described in key resources. Donald Kirkpatrick’s seminal book, Evaluating Training (1974), provided a valuable foundation because it identified four levels for evaluating training programs: participant reaction, participant learning, participant use of learning, and results, often expressed in terms of organizational benefits.

Thomas Guskey enhanced Kirkpatrick’s work and applied it to the field of education by adding a fifth level in his influential work, Evaluating Professional Development (2000). (Click here to learn about Guskey’s framework.) My own work in Assessing Impact: Evaluating Professional Learning (Killion, 2018) addresses evaluating the impact of professional learning on student success.

Thanks to these and other efforts, evaluating professional learning for its impact on educators and students has matured in the last several decades from a stance of impossible-to-do to necessary-to-do. And the focus for evaluating professional learning has sharpened into several distinct purposes, each providing essential data to make formative and summative decisions about professional learning as a vehicle for continuous improvement within school systems. Today, professional learning leaders evaluate professional learning for seven distinct purposes:

- Problem identification;

- Planning;

- Quality;

- Implementation;

- Effectiveness (changes in educators’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, aspirations, and behaviors);

- Impact on students; and

- Social justice and human rights.

1. PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION

The first purpose for evaluation is understanding the need or problem that professional learning is expected to address. Data allow planners to identify the necessary changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills, aspirations, and behaviors, which in turn inform the content for the professional learning. Analyzing available data about students, educators, the environment, resources, previous experience and success with change initiatives, scope of the change, and leadership stability are useful for these purposes.

Useful tools for this type of evaluation include the fishbone diagram; SWOT (successes, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats); fault tree analysis; positive deviance; and root cause analysis. These tools and processes are designed to gather data to identify root causes for presenting problems so that they, rather than symptoms, can be addressed (Killion, 2018).

2. PLANNING

The second purpose for evaluating professional learning is planning. This requires collaboration between evaluators and professional learning designers to ensure that the professional learning is adequately planned and sufficiently supported to produce the intended results. A solid plan for professional learning, one that is ready to be implemented and evaluated, requires clear goals for the program; specific outcomes that specify changes in educator and student knowledge, attitudes, skills, aspirations, and behaviors (KASAB) (Killion, 2018); standards and indicators of success for the goals and outcomes; a theory of change that maps out how the changes are likely to occur; and a logic model to plan for and monitor the program’s progress.

Evaluators engaging in evaluability assessments look for clear goals and outcomes, theories of change, logic models, indicators of success, and standards of success so they can assess the professional learning plan’s comprehensiveness.

Evaluating the plan can ensure that professional learning meets the definition of a “set of purposeful, planned, research- or evidence-based actions and the support system necessary to achieve the identified outcomes” (Killion, 2018, p. 10). In practice, what educators call professional learning is often reduced to training alone without the surrounding support that moves learning into practice. A planning evaluation can help determine whether that is the case and whether the plan needs to be adjusted.

A comprehensive plan integrates coaching; collaboration; safety in taking risks; ongoing and personalized support; extended learning opportunities; feedback processes; and strong leadership to maintain a focus and level of persistence to work through challenges that occur in the implementation dip and frustration associated with significant change (Killion et al., 2023). This support is necessary in varying degrees depending on the scope of the changes desired and educators’ current state of practice. Based on the goals, evaluators can determine which changes they are looking for in the plan and whether they are sufficiently represented.

3. QUALITY

To what degree does the professional learning meet the standards of high-quality? Sometimes overlapping with the planning evaluation, the quality evaluation applies a specific set of quality criteria as a benchmark against which to assess professional learning. Learning Forward’s Standards for Professional Learning, a research-based compilation of the attributes of and conditions for high-quality professional learning that produces results, serves as a useful tool for analyzing the quality of professional learning (Learning Forward, 2022). Learning Forward’s Standards Assessment Inventory (sai.learningforward.org) is a way to measure the standards in practice and is a valuable tool to analyze data for quality evaluation.

Using the elements of high-quality professional learning as criteria, professional learning leaders can gather data about how each component of the standards is integrated into the program and use those data to adapt the plan. Savvy leaders continuously evaluate the quality of professional learning design as it occurs to gain additional data, often from the participant perspective, to modify the program to address unanticipated needs or gaps.

For example, evaluators might ask if the learning experiences engage participants and promote collaboration. They might also investigate if the professional learning includes support from coaches and school administrators to facilitate changes in teacher practices and organizational support.

4. IMPLEMENTATION

This type of evaluation zeroes in on how well the actions described in the professional learning plan are being accomplished as planned and, if they are not, what barriers are interfering and need addressing. Logic models that delineate the specific actions to achieve the intended outcomes can be useful to track the implementation of those actions.

Input from learners about how they experience the actions provides helpful data about implementation. Examining the program’s various outputs, such as attendance records, documents produced to support learning, attendance records, and end-of-session satisfaction data, offers data about implementation of the professional learning.

Implementation evaluation results can be used in multiple ways. A plan poorly executed is unlikely to produce the intended results. An implementation evaluation can identify problems early on and prompt midcourse corrections to get the plan back on track. On the other hand, an implementation evaluation can also identify when the original plan requires adaptation. A plan that is insensitive to the context in which it is being implemented and unresponsive to emerging issues is also unlikely to produce the results intended.

While a thorough planning evaluation might have surfaced these challenges, they often do not become evident until the rollout of the professional learning occurs. Too frequently, evaluation ceases at this point without asking the remaining questions. But an implementation evaluation can provide the data to help designers make decisions about how to adapt the plan.

For example, program implementers may find that educators cannot access coaching support in a timely manner or that the resources provided for educator use are not aligned with the district-adopted instructional materials. This might lead to the hiring of more coaches or identification of new curricular resources.

5. EFFECTIVENESS

Transferring learning into practice is an essential step in generating results from professional learning. An effectiveness evaluation asks: Is the professional learning effective in contributing to changes in educator knowledge, attitudes, skills, aspirations, and behaviors (KASABs)?

Effectiveness may be confused with impact, yet it is distinct. Effectiveness refers to the initial and intermediate outcomes of professional learning that typically enable changes in student opportunity to learn and student success. Initial changes frequently occur in knowledge and skills, while intermediate changes are those in attitudes, aspirations, and behaviors. When these changes are fully realized, educators persist in applying new learning in practice, and results for students are more likely.

This purpose might also be confused with performance evaluation. However, it focuses on the specific practices associated with the professional learning rather than the full spectrum of role responsibilities. This evaluation requires clarification of the specific outcomes expected and sufficient ways to gather data about those behaviors. It focuses on how educators are implementing their learning as planned and if the support system meets their individual and collective needs.

Tools such as observation rubrics or checklists, walk-through guides, Innovation Configuration maps, work samples, and anecdotal data gathered from practice are useful for this type of evaluation if they are tightly aligned with the practices the professional learning intends to refine or implement.

6. IMPACT

Too frequently, evaluation ceases at the previous level — effectiveness. Yet changes in educators do not necessarily guarantee results for students. Educators may gain knowledge and skills, yet insufficiently have the commitment to implement new practices with fidelity or consistency.

Habits of practice are challenging to shift, and occasional, incomplete, or inaccurate implementation of research-based practices is often insufficient to change learning experiences for students. Impact evaluation is the only way to know if a relationship exists between professional learning and student learning.

To address this purpose, evaluators choose among several evaluation design options such as randomized or quasi-experimental trials, pseudo-causal theory of change, matched comparisons, pre-post comparisons, or post-post comparisons. Some design options are more conducive to practitioner-driven evaluation, while others are more useful in applied and basic research.

Student data of all forms, from daily formative, common, or end-of-course assessments, work products, presentations, or projects, can be used for this type of evaluation. Less useful are high-stakes assessments that might not measure the expected results of the educator practices being implemented.

For example, if a mathematics professional learning program emphasizes the implementation of student discourse and productive struggle, a state assessment may not provide data about how students are engaged in discourse and use productive struggle. Relying solely on the state’s assessment in mathematics is a mismatch between the expected results for students associated with the professional learning and what is being measured.

This type of evaluation is most helpful when it is combined with the implementation and effectiveness evaluations described above. The hypothesis evaluators formulate is this: If educators change their knowledge, attitudes, skills, and aspirations and apply the behaviors with consistency and accuracy, students’ learning opportunities will increase and their level of success will change, ideally in a positive direction.

This success will be enhanced if data about educator implementation is used to guide adjustments in the professional learning plan to address the unique combination of educator, environment, and student. A positive direction in the relationship between educator practice and student learning opportunities and success is the goal of professional learning and the measure of the impact of it.

7. SOCIAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS

A final purpose for evaluating professional learning, social justice and human rights, examines whether the professional learning is culturally responsive, contextually relevant, and accommodating of diverse needs. This kind of evaluation might occur simultaneously with any or all the other evaluations.

Questions about cultural responsiveness might be asked in the needs evaluation to determine the degree to which the full scope of the population’s needs have been examined. In a planning evaluation, evaluators might examine the proposed professional learning for representation in learning design, materials, or access. In the implementation evaluation, evaluators might analyze if resources are equitably distributed. In the effectiveness evaluation, evaluators might assess if the new practices are consistently and accurately applied in all contexts to ensure that no student is being denied opportunity to learn. And in impact evaluation, evaluators measure the degree to which student success occurs across student groups versus looking only at mean differences.

Tools such as rubrics that focus on culturally responsive pedagogy can be used to review professional plans. Focus groups of diverse participants can serve as reviewers of professional learning plans, materials, and tools. Community members with diverse backgrounds and perspectives can participate in professional learning and serve as critical friends. Interviews with educators can investigate how the professional learning program meets their unique learning needs and the degree to which they receive personalized and relevant support in transferring their new learning to practice.

STRONGER PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

While the purposes of evaluation are many and the effort may seem burdensome, this kind of investigation is vital to justify investments in professional learning and be accountable for just and fair benefits for educators and students that flow from these expenditures. Problem identification, planning, quality, implementation, effectiveness, impact, and social justice and human rights evaluations are ways educators can strengthen professional learning to increase the likelihood that their efforts and investments will pay dividends for students and educators.

Download pdf here.

Are you getting the most out of your professional learning? 🤔 These 7 key reasons point to why we must evaluate it, from problem identification to assessing student outcomes. #EduChat #EdLeaders @jpkillion Share on XReferences

Guskey, T. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin.

Killion, J. (2018). Assessing impact: Evaluating professional learning (3rd ed.). Corwin & Learning Forward.

Kirkpatrick, D. (1974). Evaluating training programs: The four levels. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Learning Forward. (2022). Standards for Professional Learning. Author.

Joellen Killion is a senior advisor to Learning Forward and a sought-after speaker and facilitator who is an expert in linking professional learning and student learning. She has extensive experience in planning, design, implementation, and evaluation of high-quality, standards-based professional learning at the school, system, and state/provincial levels. She is the author of many books including Assessing Impact, Coaching Matters, Taking the Lead, and The Feedback Process. Her latest evaluation articles for The Learning Professional are “7 reasons to evaluate professional learning” and “Is your professional learning working? 8 steps to find out.”

Categories: Continuous improvement, Data, Evaluation & impact, Implementation

Recent Issues

WHERE TECHNOLOGY CAN TAKE US

April 2024

Technology is both a topic and a tool for professional learning. This...

EVALUATING PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

February 2024

How do you know your professional learning is working? This issue digs...

TAKING THE NEXT STEP

December 2023

Professional learning can open up new roles and challenges and help...

REACHING ALL LEARNERS

October 2023

Both special education and general education teachers need support to help...