FOCUS

Students on the margins

Coaching for engagement and achievement

By Jim Knight

Categories: Coaching, Equity, Learning designs, Social & emotional learningDecember 2019

Vol. 40, No. 6

My friend and mentor Don Deshler has directed more than 200 studies in his career and, in the process, significantly shaped how we understand and respond to students who are at risk for failure.

One study in particular changed the way Deshler thought about his research. To see the school experience through students’ eyes, he and his fellow researchers at the University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning each observed one student for a full school day.

“The results,” Deshler told me, “were gut-wrenching. Students who were at risk lived on the margins, even in the hallways and cafeteria. I saw the loneliness in the kids’ eyes. It made me question how much I had missed about the experiences kids have in school. I wondered if we’d had blinders on about what students needed because we didn’t really see that school was such a lonely experience for far too many students.”

What Deshler learned by observing students is similar to what I have learned as I have been studying instructional coaching for more than 20 years. If we are to help teachers move students away from the margins and into the heart of schools, coaching needs to address student engagement, in addition to and as part of student achievement. Both are important, and both should be central to any effective instructional coaching program.

Coaching needs to address student engagement as well as achievement. @jimknight99 #LearnFwdTLP Click To TweetWhy engagement matters

Engagement is an essential part of a meaningful life, no less so for students than for adults. Students who are in healthy relationships are engaged by their friends and family. Students who are productive learners engage in learning activities. Most important, students who stay in school do so because they are engaged, as research clearly shows (CDC, 2009; Finn, 1993; Finn & Rock, 1997; Knesting, 2008). Therefore, all of us who work to improve schools must make sure that students are engaged.

Coaches should play a role in building student engagement because they influence what teachers do and therefore what students experience. Indeed, one peer-reviewed study we conducted found that instructional coaching had a significant impact on student engagement, with an effect size of 1.02 (Knight, Hock, Skrtic, Bradley, & Knight, 2018).

Instructional coaching

Instructional coaches partner with teachers to improve teaching to have a positive impact on student learning and student well-being (Knight, 2018). Effective instructional coaches see coaching as a partnership or professional conversation between equals within which collaborating teachers make the decisions about what happens in their classroom.

Coaching, according to van Nieuwerburgh (2017), is “a managed conversation between two people” (p. 5) during which coaches artfully use specific skills, such as purposeful listening, powerful questions, paraphrasing, and summarizing to empower people to “unlock … [their] potential to maximize their own performance” (Whitmore, 2017, pp.12-13).

Effective instructional coaching involves not only strategic knowledge, but an intentional process. Research by my colleagues and me (e.g. Knight, 2018) suggests that effective coaches use a coaching cycle process that involves three stages: identify, learn, and improve. ''Research suggests that effective coaches use a coaching cycle process that involves three stages: identify, learn, and improve.'' @jimknight99 #LearnFwdTLP Click To Tweet

During the identify stage, instructional coaches partner with teachers to identify a clear picture of the current reality in the classroom (including how engaged students are), a goal, and a strategy that teachers can use to try and hit the goal.

To help teachers get a clear picture of their practice, coaches often video record lessons and share the video with teachers. This is especially helpful for engagement because it allows teachers to examine students’ actions and reactions.

Coaches and teachers then create goals that we refer to as PEERS goals: powerful, easy to implement, emotionally compelling for teachers, reachable (involving a measurable outcome and an identified strategy teachers can use to attempt to hit their goal), and student-focused.

During the learn stage, coaches get teachers ready to implement a new strategy by describing the strategy precisely but provisionally. That is, coaches explain the strategy while also encouraging teachers to make adjustments to meet the unique needs of their students.

Coaches also often provide some kind of model so that teachers can see the strategy being implemented, either by the coach, another teacher, or on video.

Finally, during the improve stage, teachers try out the strategies and coaches and teachers make adaptations together until the original goal, or a modified goal, is met.

Measuring engagement

Instructional coaches who partner with teachers to set student engagement goals and monitor progress toward those goals must be able to describe and measure engagement and be familiar with strategies to improve it.

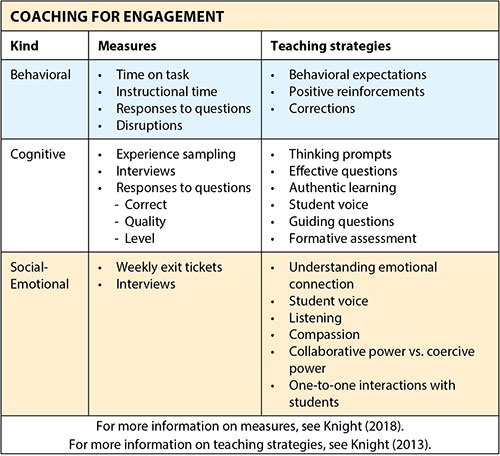

Researchers have identified three major categories of engagement: behavioral, cognitive, and social-emotional. (See the table above.) Here are ways to measure each category and provide teaching strategies teachers can use as they strive to empower students to hit engagement goals.

Researchers have identified three major categories of engagement: behavioral, cognitive, and social-emotional. @jimknight99 #LearnFwdTLP Click To TweetBehavioral Engagement: On-task behavior

When students are behaviorally engaged, they are doing what they are supposed to be doing — that is, they are on task. The advantage of behavioral engagement is that it is objective and measurable. For example, you can see if students are doing the think, pair, share collaboration you asked them to do.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t measure whether students are actually learning. However, that does not mean that behavioral engagement is a useless measure. When many students are off task, getting them on task is often a necessary starting point.

Measuring behavioral engagement. Coaches can use at least four simple measures to assess behavioral engagement and obtain information they can share with teachers:

- Time on task: Measure whether students appear to be doing the task that is set before them;

- Instructional time: Subtract transition time from the total length of a lesson;

- Student disruptions: Count the number of times students interrupt the teacher’s instruction or other students’ learning; and

- Number of questions: Count the number of student responses and the number of different students responding to the teacher’s questions.

Improving behavioral engagement. Three strategies are most frequently mentioned in the literature for increasing behavioral engagement: expectations, reinforcement, and corrections.

Expectations clarify how students are expected to behave during all activities and transitions. Reinforcements — teachers communicating that they see students acting appropriately — are essential since teacher attention is an important motivator for student behavior.

Finally, fluent corrections are essential because when inappropriate behavior is not corrected, it frequently grows and spreads in a classroom. Coaches may choose to work with teachers on using one or more of these strategy types to address off-task behavior.

Cognitive Engagement: Authentic engagement

When students are cognitively engaged, they are experiencing the thinking their teacher intended them to experience from an activity. Schlecty (2011) makes a useful distinction between what he refers to as authentic engagement and strategic compliance.

When students are strategically compliant, they are doing something for a strategic reason rather than to learn. In contrast, when students are authentically engaged, they find meaning and value in learning tasks and are attentive, committed, and persistent to complete them.

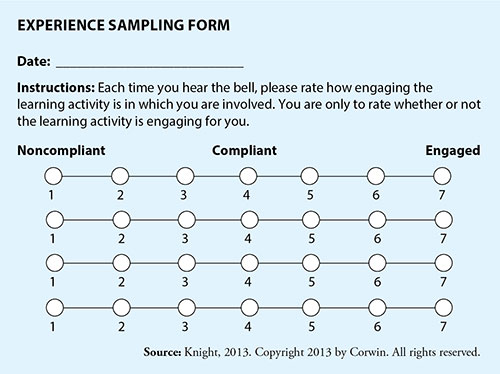

Measuring cognitive engagement. Since cognitive engagement mostly occurs “inside” the student rather than outside, we have found that the best data come from asking students to communicate their opinion about their engagement in learning activities.

This may involve the coach interviewing students, asking students to respond to exit tickets, or using what we refer to as experience sampling, which prompts students to report their level of engagement at different times during a lesson on a form such as the one above.

Improving cognitive engagement. When students are learning, they are likely to be cognitively engaged. Increasing cognitive engagement, like increasing achievement, usually involves at least three teaching strategies that coaches can support teachers to use: a clear description of learning outcomes, formative assessment, and feedback. Other strategies include thinking prompts, effective questions, authentic learning, and student voice.

Emotional Engagement: Connectedness, belonging, and physical and psychological safety

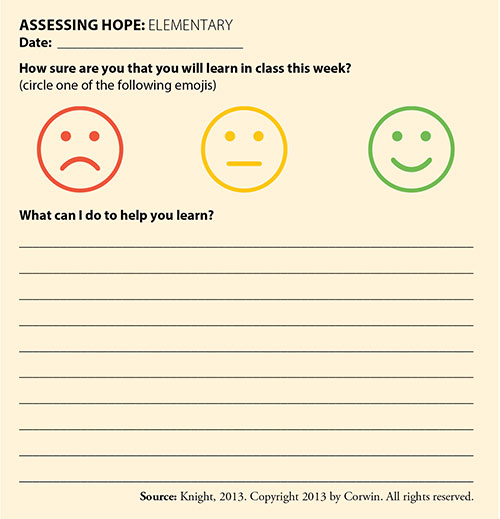

When students are emotionally engaged, they feel they belong in their school, they are physically and psychologically safe, their experiences in school are positive and meaningful, they have friends, and they have hope.

According to many of the educators my colleagues and I meet, emotional engagement is a prerequisite for all learning. That is, if a student feels alone, afraid, or hopeless, we need to address those challenges before he or she can engage deeply in academic learning.

Measuring emotional engagement. As with cognitive engagement, we need to ask students about their emotions to understand them. One way to do this is to have students complete a weekly informal assessment about their emotional state and ask what could be done to make their experiences more positive.

Coaches and teachers can work together to use these informal assessments of students’ positive emotions, relationships, safety, or hopes to establish and monitor progress toward a goal. For example, using surveys, coach-teacher pairs can set goals such as “at least 90% of my students will report each week that they feel able to learn in my classroom.” An example of a simple survey for elementary students is shown in the assessment form in the sidebar. (More detailed questions are appropriate for older students and can be found in Knight (2013).)

Also, coaches can interview students about their experiences in school and share the results with teachers. Formal surveys, such as the Gallup student success survey, may provide a more global understanding of student engagement or establish benchmarks. Teachers can assess students’ emotional engagement through interactive journals in which students and teachers write back and forth to each other each week.

Improving emotional engagement. All of the strategies to increase behavioral and cognitive engagement should also have a positive impact on emotional engagement. In addition, coaches can help teachers enhance their relationships with students.

For example, teachers can video record their lessons and review them with the coach to reflect on whether they demonstrate empathy and how they manage such variables as power in the classroom. Collaborative power is more likely to build connections than coercive power.

Teachers can demonstrate collaborative power by giving students their full attention, avoiding sarcasm or power tripping, affirming all students, communicating respect, and so forth. Additionally, teachers can increase the number of positive interactions they initiate with students and monitor how they connect emotionally with their students.

Other strategies coaches can work on with teachers include: building connections by learning about students’ unique interests and activities through surveys and informal conversations; conflict resolution approaches such as restorative justice or collaborative problem-solving; and involving students more directly in decisions about what and how they learn.

Simply listening to students’ voices has been shown to significantly increase student success (Quaglia & Corso, 2014) but this is more complicated than it sounds and is an area ripe for coaching support.

Bringing It All Together

The impact cycle provides the structure for coaching conversations and the engagement definitions, measures, and teaching strategies provide tools for cycles that dramatically increase student engagement.

Identify

After the coach and teacher identify a clear picture of reality, they can set goals based on the measures of engagement described in this article. Following this, they can discuss which strategies to use to lead students to hit their goal.

For most coaches, creating an instructional playbook prepares them to support teachers and communicate their explanations more clearly. An instructional playbook contains checklists and other tools coaches create to help them understand and describe the high-impact teaching strategies they most frequently share with teachers (Knight, Hoffman, Harris, & Thomas, in press).

Learn

During the learn stage, the coach and teacher collaborate to identify how the teacher will implement the new strategy. Coaches usually provide an opportunity for teachers to see the practices in use by modeling them in the teacher’s classroom, sharing a video, or covering a class so the teacher can visit another teacher who uses the strategy to be learned.

Improve

When teachers implement a strategy, they usually don’t get the results they were hoping for immediately. The coach and teacher usually have to explore various adaptations, including changing the goal, the way a goal is measured, the way a strategy is taught, or the strategy itself.

For example, teachers may start measuring authentic engagement by assessing how many students are correctly answering questions and then switch to experience sampling to gain a better understanding of whether students are engaged during a lesson.

Throughout the three stages, it is important to understand that each cycle is different. The best coaches, like artists, use the right tools at the right times.

Engagement and achievement

A focus on engagement should not turn us away from the importance of coaching to increase achievement. Everyone wants students to flourish academically, and coaching has to have an unmistakably positive impact on student learning.

However, to meet all the needs of all students and bring all students in from the margins, coaches need to partner with teachers to address engagement because engagement and achievement go hand in hand.

Coaches need to partner with teachers to address student engagement because engagement and achievement go hand in hand. @jimknight99 #LearnFwdTLP Click To TweetTo learn more

For more information on the research supporting the claims in this article, visit instructionalcoaching.com/research.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Fostering school connectedness. Available at www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/pdf/connectedness_administrators.pdf.

Finn, J.D. (1993). School engagement and students at risk. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Finn, J.D. & Rock, D.A. (1997). Academic success among students at risk of school failure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 221-234.

Knesting, K. (2008). Students at risk for school dropout: Supporting their persistence. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 52(4), 3-10.

Knight, J. (2013). High-impact instruction: A framework for great teaching. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Knight, J. (2018). The impact cycle: What instructional coaches should do to foster powerful improvements in teaching. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Knight, D., Hock, M., Skrtic, T.M., Bradley, B.A., & Knight, J. (2018). Evaluation of video-based instructional coaching for middle school teachers: Evidence from a multiple-baseline study. The Educational Forum, 76, 50-51.

Knight, J., Hoffman, A., Harris, M., & Thomas, S. (in press). The instructional playbook: The missing link for translating research into practice. Lawrence, KS: One Fine Bird Press.

Quaglia, R. & Corso, M.J. (2014). Student voice: The instrument of change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Schlechty, P. (2011). Engaging students: The next level of working on work. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

van Nieuwerburgh, C. (2017). An introduction to coaching skills: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Whitmore, J. (2017). Coaching for performance: The principles and practice of coaching and leadership (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Categories: Coaching, Equity, Learning designs, Social & emotional learning

Recent Issues

TAKING THE NEXT STEP

December 2023

Professional learning can open up new roles and challenges and help...

REACHING ALL LEARNERS

October 2023

Both special education and general education teachers need support to help...

THE TIME DILEMMA

August 2023

Prioritizing professional learning time is an investment in educators and...

ACCELERATING LEARNING

June 2023

Acceleration aims to ensure all students overcome learning gaps to do...