FOCUS

Which way to the principal’s office?

By Suzanne Bouffard

Categories: Career pathways, Leadership, Standards for Professional LearningDecember 2023

Many professions have long runways to leadership, with mentorship and increasing levels of responsibility. Lead prosecutors start as assistant district attorneys, surgeons often complete a fellowship after residency, many business and nonprofit leaders move through the ranks of assistant director or vice president.

In contrast, the path to school leadership has historically not been well-defined. But that is changing. The role of assistant principals has become a major stepping stone to the principalship. Among today’s head principals, three-quarters have previously worked as assistant principals, and the ranks of assistant principals are increasing at a rate six times that of principals (Goldring et al., 2021a).

Once thought of primarily as disciplinarians, assistant principals are now seen as key members of school leadership teams and an important part of building the principal pipeline. With responsibilities that include instructional leadership and professional learning, and with opportunities for close observation of and mentoring by principals, assistant principals are poised on a springboard to the next step.

The traditional path to school leadership is evolving. Learn how targeted support

The traditional path to school leadership is evolving. Learn how targeted support  and intentional development can guide the key players – assistant principals – to successful leadership. #Principals #ProfDev #TheLearningPro Share on X

and intentional development can guide the key players – assistant principals – to successful leadership. #Principals #ProfDev #TheLearningPro Share on X

But making sure the dive off that board results in successful leadership and great student outcomes takes intentionality and support, at the individual level and a systemic one. That is one of the conclusions of The Wallace Foundation’s multiyear initiative to support the development of principal pipelines, from teacher leadership to the assistant principalship, all the way through principal supervision.

The initiative has found that when systems create comprehensive and aligned pipelines to identify, prepare, and support principals, student achievement increases more than 6 percentile points in reading and almost 3 percentile points in math (Gates et al., 2019). Comprehensive and aligned means that they include multiple entities, including higher education institutions, districts, and schools, and that they support all phases of the development process. Some of those phases have been underused, or even untapped, and research suggests that the assistant principalship is one of them (Goldring et al., 2021a).

When districts recognize the potential of assistant principals and are intentional about supporting them to become successful principals, they can achieve three goals, according to research commissioned by Wallace: diversify the principalship, prepare effective principals, and achieve equitable outcomes for students (Goldring et al., 2021a). Those are big payoffs, especially at a time when principal attrition is growing (Levin et al., 2019) and student achievement is flagging (The Nation’s Report Card, 2023).

Need for support

Historically, role-specific support for assistant principals has been lacking. According to a synthesis of 79 empirical research studies on assistant principals published since 2000 (Goldring et al., 2021a), gaps include evaluation processes and rubrics, sequential leadership development opportunities, mentorship and opportunity for people of color, and role-specific professional learning, despite the fact that learning that is relevant to one’s position and set of responsibilities is a key component of high-quality, standards-based professional learning (Learning Forward, 2022).

Unlike principals, who can look to the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (NPBEA, 2015), assistant principals do not have the benefit of standards that can be used to drive evaluation, professional learning, and identification and preparation for the next step in the leadership pipeline.

Researcher Ellen Goldring, who co-authored the research synthesis, pointed out in an interview with The Wallace Foundation (Gill, 2021) that, “In most cases, principals and assistant principals are evaluated on the same rubric … In one study, the assistant principals did not even know if they were formally evaluated or how. Another study mentioned the complexity of using the same rubric: If I’m an assistant principal and evaluated on the same rubric as the principal, does that mean I can never be exemplary because that’s only for principals?” She noted that this creates confusion about the types of tasks and leadership opportunities that assistant principals should have.

The gaps in support for assistant principals are magnified in rural areas and small districts and for educators of color (Goldring et al., 2021a). Educators of color are more likely than white educators to become assistant principals, yet they are less likely to become principals than their white colleagues. Research suggests several possible reasons for this, including discrimination in hiring and less access to mentoring, especially for females of color.

Unlocking assistant principals' potential is crucial for diversifying leadership & achieving equitable student outcomes. A @WallaceFdn initiative spotlights the importance of comprehensive pipelines & targeted support.… Share on X

Unlocking assistant principals' potential is crucial for diversifying leadership & achieving equitable student outcomes. A @WallaceFdn initiative spotlights the importance of comprehensive pipelines & targeted support.… Share on X

Opportunity for change

The Wallace Foundation’s Principal Pipeline Initiative shined light on these needs and provided an opportunity for district partners to be more strategic about helping assistant principals develop into principals. The initiative included six urban school districts working to identify, recruit, and support high-quality school leaders. The foundation also invested in understanding and supporting the roles of principal supervisors and university preparation programs for school leaders.

As part of this work, Policy Studies Associates recently produced Assistant Principal Advancement to the Principalship: A Guide for School Districts (Booker-Dwyer et al., 2023). The guide is designed to be used by a team dedicated to advancing assistant principals to foster commitment, consistency, and follow-through. The guide’s authors recommend that the team be led by a district-level champion who has the support of senior leaders and include members such as the superintendent, chief of human resources, principal supervisors, principals, assistant principals, principal coaches, and equity officers.

Drawing on research, an evaluation of the Principal Pipeline Initiative districts, and input from diverse district leaders, the guide provides steps districts can take to support assistant principals, along with reflection questions to consider how well those steps are progressing and where to place more effort. It is a valuable tool for professional learning leaders because it can help sharpen the focus on supporting assistant principals not just for their current jobs but for their own and their district’s long-term goals.

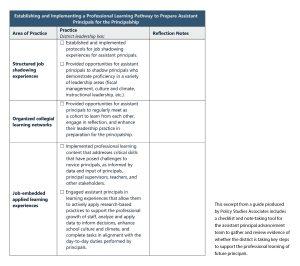

These steps are organized into three interconnected components, all of which are consistent with Learning Forward’s Standards for Professional Learning: forecasting principal vacancies (Evidence standard), identifying assistant principals who have the potential to succeed as principals (Equity Foundations and Resources standards), and implementing professional learning pathways to prepare them for the principalship (Professional Expertise and Leadership standards). All are driven by an equity lens, with an emphasis on identifying and supporting leaders and potential leaders from diverse backgrounds (Equity Drivers standard) (Learning Forward, 2022).

Professional learning’s role

Like all educators, assistant principals benefit from ongoing professional learning on many aspects of their jobs. But professional learning to prepare them for the next step is a specific niche that is often overlooked. The Policy Studies Associates guide’s authors point out, “Professional learning experiences provided by school districts to prepare assistant principals for the principalship serve to bridge a gap between core content assistant principals learned through university preparation programs and the actual roles and responsibilities of principals” (Booker-Dwyer et al., 2023).

Recommended professional learning approaches to serve this function include:

- High-quality mentoring and coaching;

- Structured job shadow experiences with a variety of principals;

- Organized collegial learning networks;

- Applied learning; and

- Targeted training on addressing the needs of diverse learners.

All of these forms of learning are sustained, job-embedded, and consistent with the Learning Designs standard of the Standards for Professional Learning (Learning Forward, 2022). They are about facilitating a process of development and growth over time, a process that should start as early as possible.

The topics covered in these learning experiences should be driven by the skill sets principals need and the areas the district has identified as lacking. The guide recommends using surveys, interviews, and focus groups with novice principals and their supervisors to help determine what those needs and missing links are: “For example, if your district finds that novice principals face challenges with fiscal management, then the district can add targeted learning that focuses on budgeting and sound fiscal practices to the professional learning pathway” (Booker-Dwyer et al., 2023).

The guide includes a checklist and note-taking tool for the assistant principal advancement team to gather and review evidence of whether the district is taking key steps to support the professional learning of future principals. (See p. 48.) Practices that have not yet been implemented can serve as a starting point for developing an actionable work plan.

That work plan should be based on a holistic review of all the practices and on district priorities and capacity and be informed by the Standards for Professional Learning to ensure that the professional learning is high quality.

The work plan is most likely to be beneficial if it is connected to the other parts of the principal pipeline process. Learning to be an excellent principal is an ongoing process that does not stop when assistant principals take on new roles as principals. New and experienced principals’ needs have typically evolved beyond those of new assistant principals, but they build on existing skills and experiences and therefore should be considered holistically.

It takes a village

Creating professional learning systems for assistant principals to become successful principals takes many entities and roles working together. Key players include district-level leaders who set policies and allocate funding as well as principal supervisors who work at and across schools.

In several districts that participated in the Principal Pipeline Initiative, principal supervisors facilitated professional learning for assistant principals or connected one-on-one in ways that helped identify promising assistant principals and also facilitated continuity across the support continuum (Goldring et al., 2021a).

Current principals also play a role in supporting and mentoring assistant principals to take the next step. As Beverly Hutton of the National Association of Elementary School Principals pointed out in a webinar hosted by The Wallace Foundation (Goldring et al., 2021b), the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders explicitly include the responsibility of mentorship of assistant principals.

Universities are important players, too. They can be part of planning the continuum of preparation and support for assistant principals and principals. Some universities partner with local districts to organize ongoing professional learning. Even those that don’t have the capacity to do so can partner with districts to understand their principal candidates’ needs and how their leadership preparation programs can provide the most solid foundation of support (Goldring et al., 2021b).

Maximize potential

Professional learning for assistant principals is a key part of the leadership pipeline, but it is not the only one. The lessons of the Principal Pipeline Initiative show that maximizing the potential of assistant principals should also include efforts to clarify the role of the assistant principalship as a stepping stone to the principalship; develop standards, leadership tasks, and evaluation processes consistent with that role; ensure principals have the skills to mentor assistant principals; and develop principals’ awareness of and practices for advancing equity in the leadership pipeline.

When all the pieces are in place, assistant principals’ vital contributions to their schools and the field become more visible and continue to grow.

Download pdf here.

Professional learning for assistant principals is a game-changer in the journey to the principal's office. Discover strategies that bridge the gap and prepare assistant principals for effective leadership. #ProfDev #EdChat… Share on X

Professional learning for assistant principals is a game-changer in the journey to the principal's office. Discover strategies that bridge the gap and prepare assistant principals for effective leadership. #ProfDev #EdChat… Share on X

References

Booker-Dwyer, T., Aladjem, D.K., Fletcher, K., & Eyer, B. (2023). Assistant principal advancement to the principalship: A guide for school districts. Policy Studies Associates.

Gates, S.M., Baird, M.D., Master, B.K., & Chavez-Herrerias, E.R. (2019). Principal pipelines: A feasible, affordable, and effective way for districts to improve schools. RAND Corporation.

Gill, J. (2021, May 18). Shining the spotlight on assistant principals. The Wallace Foundation.

Goldring, E., Rubin, M., & Herrmann, M. (2021a). The role of assistant principals: Evidence and insights for advancing school leadership. The Wallace Foundation.

Goldring, E., Rubin, M., & Herrmann, M. (2021b). The role of assistant principals: Evidence and insights for advancing school leadership [webinar]. The Wallace Foundation. wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/the-role-of-assistant-principals-ppt-presentation.pdf

Learning Forward. (2022). Standards for Professional Learning. Author.

Levin, S. & Bradley, K. (2019). Understanding and addressing principal turnover: A review of the research. NASSP & Learning Policy Institute.

National Policy Board for Educational Administration. (2015). Professional Standards for Educational Leaders. Author.

The Nation’s Report Card. (2023). NAEP long-term trend assessment results: Reading and mathematics. www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/ltt/2023/

Suzanne Bouffard is senior vice president of communications and publications at Learning Forward. She is the editor of The Learning Professional, Learning Forward’s flagship publication. She also contributes to the Learning Forward blog and webinars. With a background in child development, she has a passion for making research and best practices accessible to educators, policymakers, and families. She has written for many national publications including The New York Times and the Atlantic, and previously worked as a writer and researcher at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She has a Ph.D. in developmental psychology from Duke University and a B.A. from Wesleyan University. She loves working with authors to help them develop their ideas and voices for publication.

Categories: Career pathways, Leadership, Standards for Professional Learning

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...