FOCUS

Thinking routines help educators develop an equity lens

By Rachel Bello, Tarima Levine and Matty Lau

Categories: Continuous improvement, Reaching all studentsApril 2023

The phrase “educational equity” is a common one in schools today, but it can mean many things to many people, leading to a lack of clarity about where and how educators can best focus their energies. In spring 2022, the continuous improvement team at the Bank Street Education Center (the Ed Center) set out to articulate what it means to “center equity” in our work with school districts and how to ensure that we do so consistently.

We have identified a series of thinking routines that we use regularly to infuse equity-mindedness into our work. These thinking routines help us ensure that we prioritize equity during the project design, implementation, and formative evaluation of our improvement efforts. This article describes how we embed those routines in the tools and approaches we use in coaching for continuous improvement and shares early insights about how they are helping.

Our Approach

A commitment to equity has been a long-standing core value of the Bank Street College of Education. Since its inception in 1916, Bank Street has focused on improving the education of all children and their teachers by applying all available knowledge about learning and growth and connecting teaching and learning meaningfully to the outside world. Today, the Ed Center is the arm of the institution that partners with school systems around the U.S. to collaborate on educational improvement.

The Ed Center’s goal is to disrupt inequity and design better learning experiences for everyone — students, families, and school and district leaders — but especially for those who have been historically marginalized by traditional schooling in America. We do this critical work by partnering closely with stakeholders at every layer of the system.

As we reflected on our work with schools and districts, we at the Ed Center noticed some key equity-oriented features that were critical for relationships between school professionals and students, as well as between school professionals. These reflections were informed by our reading about and exploration of equity, especially from notable works by Elena Aguilar (2020) and Glenn Singleton (2014).

Out of these reflections, we developed the following five thinking routines to embed in our work to help us and our school partners apply an equity lens.

- Unpack biases: We consistently examine and challenge our assumptions and biases and those of our partners. This means that we consider our racial and social identities and how our identities may influence our thinking or our approach to instruction.

- Look holistically: We look for complete stories and holistic pictures of what is happening for students, teachers, and leaders. This requires us to take an inquiry stance in all elements of our partnerships.

- Honor humanity: We strive to make sure we are honoring the full humanity of our students (and the adults we partner with) in all of our work and conversations. This means the “whole child” is centered in our work — not just their grades or their behaviors, but their entire identities.

- Consider power: We consider how power and privilege influence interactions and relationships, drawing on our reflections about our own social identities.

- Disrupt racism: We intentionally acknowledge and work to disrupt systemic and structural oppression by race. This means we question districtwide policies — for example, those on grading, tracking, and discipline — that disproportionately impact specific groups of children or families for reasons beyond their control or that result from decades of systemic exclusion and oppression.

Two Networks, One Charge

The Ed Center applies these thinking routines with two New York-based improvement networks in Yonkers and Brooklyn. The Yonkers Public Schools Network for School Improvement began in 2018 with Yonkers, a city about 30 minutes north of New York City. Initially, the network consisted of 10 schools and expanded in 2020 to include all 23 Yonkers schools that serve 7th and 8th graders. The Brooklyn South Network for School Improvement launched in 2020. This network comprises 11 New York City public schools across Districts 17 and 18 in the southern part of Brooklyn.

Schools in both networks are working to address a common, deep-seated injustice: Due to systemic factors beyond their control, students who are Black, Latinx, or experiencing poverty are disproportionately underprepared for success in upper-level mathematics courses. Accordingly, our overall goal is to increase the percentage of students from these groups who are on track for success in high school mathematics by the end of 8th grade.

We support both networks in their continuous improvement work via all-network meetings, school-based coaching, school leader meetings, and district strategy meetings. In Brooklyn, we have also established a cadre of teacher continuous improvement leaders who meet regularly to inform the design of our program and build teacher leadership capacity.

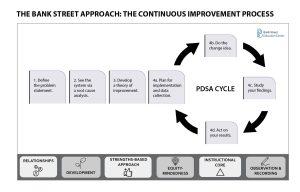

At the heart of this work are plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles, a structure for identifying a problem of practice, designing and implementing a change idea to address it, studying and reflecting on the results, and making modifications to improve on the change idea. (See the figure on below.)

In this work, we have found that the thinking routines are critical in maintaining an open dialogue with practitioners that consciously centers students and race. Without deliberately making these elements a part of each phase of the repeated PDSA cycle, that critical and sometimes necessarily uncomfortable conversation can get pushed aside.

What follows are a few examples of how we apply the thinking routines in our network facilitation. Rather than being isolated strategies, the thinking routines work together in integrated ways, and so we describe them in tandem. We focus on the first four thinking routines because these emerge most readily in our coaching work with school teams. While all our work is ultimately designed to disrupt systemic inequities, the fifth thinking routine shows up more often in our larger-scale work with district partners.

Identify student needs and strengths.

Before school teams engage in running plan-do-study-act cycles, we invite each team member to select three to five focus students to follow throughout the year. This provides network members with an initial way to determine if the change idea is leading to improvement, and if so, for whom and under what conditions. Teachers were asked to select students who identify as Black, Latinx, or experiencing poverty, score C or below in math, consistently attend class, and could potentially benefit greatly from additional attention in math class.

However, we are mindful that educators engaged in this process could risk falling into a deficit mindset about what these students can do or who they are. We want to reinforce that students are more than just the challenges they face or the grades they are not (yet) receiving.

To help educators shift from associating children with largely deficit-oriented criteria to seeing them as whole human beings, we ask network members to consider what they have learned about their focus students — either from informal conversations or a more structured empathy interview protocol — to identify and document students’ strengths, like “takes risks in class” and “loves to help others.”

This activity addresses the first three thinking routines (unpack biases, look holistically, and honor humanity) by pushing the entire network to consider the biases that can surface when we are asked to identify students who need additional support and reminding us of the ways we can build on students’ strengths to support them.

Examine data from a place of awareness.

Once teachers select focus students, they begin the process of testing instructional change ideas and collecting data on whether the change had the intended impact on student learning or students’ perceptions of the classroom environment. To facilitate studying this data, our analysts (in cooperation with our coaches) designed an interactive spreadsheet that serves as a way to collect plan-do-study-act cycle data and as a home for the protocols that participants need to collaboratively plan, study, and act on their learnings.

Each teacher has their own individual data page, which is public, so that everyone on the team or in the network can see and reflect on one another’s learnings. The data from these individual pages populate a collective team page for each improvement cycle, which serves as an organizing tool to help team members collaborate and make data-informed decisions about next steps. At each phase of the cycle, a short protocol embedded in the workbook guides team discussions and documentation.

Attention to equity is intentionally embedded in the workbook. Specifically, reflection questions and prompts remind teachers to engage in the thinking routines for unpacking biases, looking holistically, and considering power when studying data habits. We also provide explicit guidance so teams remember to use low-inference language when reviewing data, remain user-centered, consider multiple perspectives (especially students’), focus on strengths and improvements among community members early and often, and consider social identities and interrogate biases and beliefs throughout the process.

A study protocol draws on the thinking routines to prompt teachers’ reflection. The first two questions in the protocol ask teams: “What patterns do we notice about the students we seem to be serving well as a team?” and “What patterns do we notice about the students we are not reaching yet as an improvement team?”

By asking teachers to consider first the students whom they are “serving well,” we gently remind the teacher that they are working on behalf of their students and that they are a gatekeeper to student mastery. The phrase “students we are not reaching yet” is also key. Embedded in the term “yet” is the reminder that all students can learn with the right support, and the teacher is the adult charged with providing those supports. These questions are meant to create the context in which teams can look more holistically at the data patterns and draw more complete stories about what is happening for all of their students.

The study protocol also includes a question that draws attention to how teachers consider the impact of their social identities on their understanding of the data: “Think about your social identities. What assumptions or interpretations might you be making about your team’s learnings?” This question is meant to remind teachers that, in many cases, their gender expression, racial identity, or class background may bias the ways in which they interpret data. By identifying and naming these implicit biases and recognizing how they impact our judgment, the network community can take steps toward racial equity one individual and team at a time.

By encouraging participants not to jump to conclusions, we explicitly ask them to unpack their biases while they consider their practice. Considering multiple perspectives and staying strengths-based helps teachers consider the presence of a whole story behind a single data point. This deliberately helps discourage the “these kids can’t” deficit-based narrative that can often pervade conversations about teaching students who have been historically underserved.

Reminding teachers that they invariably bring their own social identities to this work also serves as a reminder to consider their power and privilege. Because there is an inherent privilege in teachers examining students’ performance, a power dynamic exists any time we look at data. We need to wield that power thoughtfully, empathetically, and equitably if we are to help students (and their teachers) improve.

Disrupt inequity

Too often in the work of educational improvement, reformers have fallen into the trap of believing that efforts to help all students will automatically benefit the most vulnerable. We now know that this is not enough; a rising tide does not raise all boats equally. Instructional improvement agents must constantly and consciously focus on helping those marginalized by the deeply inequitable structures embedded in all educational systems.

If we, as improvers, can explicitly identify bias, deficit thinking, and racism in our approaches and shift to more holistic, strengths-based, and humane practices, we can, over time, disrupt the historical inequities that have plagued our public school system for far too long. Thinking routines for equity are one way to move in that direction.

Download pdf here.

Bank Street’s grounding beliefs

Bank Street’s work is grounded in a set of core beliefs about teaching and learning. These are beliefs about the importance of relationships, taking a developmental approach, being strengths-based, maintaining equity-mindedness, focusing on the instructional core, and leveraging the power of observations, recording, and reflection.

Although all of these beliefs influence the thinking routines we discuss in this article, equity-mindedness is particularly important. This belief is used as a lens to disrupt instructional, institutional, and sociohistorical patterns of exclusionary practices and racism to drive our work on behalf of students.

References

Aguilar, E. (2020). Coaching for equity: Conversations that change practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Singleton, G.E. (2014). Courageous conversations about race: A field guide for achieving equity in schools. Corwin Press.

Categories: Continuous improvement, Reaching all students

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...