IDEAS

Literacy success story highlights the power of professional learning

By Jefna M. Cohen

Categories: Data, Outcomes, Reaching all studentsJune 2024

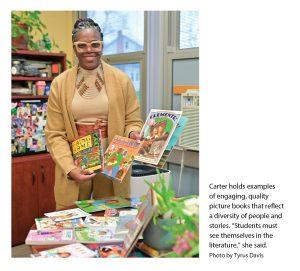

Principal Syeda Carter has a literacy success story to tell. It’s a tale of determination, learning, and overcoming obstacles that leads to achieving one of the most important goals of education: ensuring every child can read.

At the root of this story is Carter’s participation in the Learning Forward Academy, a multiyear, high-quality professional learning experience. When Carter, principal of John Fenwick Academy in Salem, New Jersey, began the academy in 2013, the percentage of 2nd graders in the school reading at grade level hovered around 40%.

Carter set an ambitious goal: 90% of 2nd graders attending for at least two years would be reading at or above grade level on entering 3rd grade. She devoted herself to learning how to achieve it. In 2023, Carter’s students met that goal, and she is determined to help them maintain that high level of achievement going forward.

To get where they are now, Carter and her colleagues made a serious investment of time and significant changes in the pre-K-2 school. They adopted a new curriculum and an assessment system, integrated coaching into their work, refreshed the school’s library collection, and put as many books into students’ hands as possible.

They pushed back against chronic absenteeism and tardiness, highlighted parent education, and steadily developed a school culture of reading. All of those efforts were grounded in the educators’ commitment to continually learning and improving.

How has she maintained her unwavering dedication to this literacy goal over many years? “I’ve been in education for 31 years,” Carter says. “When the call is strong, you do everything possible to ensure these kids move.”

The power of raising expectations

When Carter became the first Black principal of John Fenwick Academy in 2010, the student population was 87% Black. She was committed to working against assumptions that the students weren’t capable. She started with a goal to improve literacy, motivated by the high probability that if students are not reading at or above grade level by 3rd grade, they may not graduate from high school (Lesnick et al., 2010).

One of the key things she did was raise the reading assessment expectations for students. This meant an increase in the difficulty it took to achieve a reading level, differing from how the school had previously classified its young scholars.

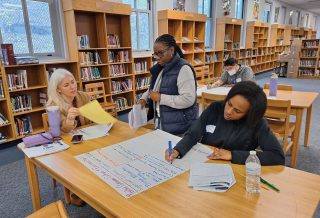

Many staff were not pleased with this new determination because it meant every adult would have to work harder to meet it. Some left in Carter’s first years as principal, but she was undaunted. She built a learning community among the staff who remained with the new staff, giving all educators the opportunity to engage in learning rounds.

They visited colleagues’ classrooms and provided feedback to each other to promote best practices around the district’s look-fors in classroom instruction: higher-order thinking questions, think time, student engagement, and feedback.

To motivate her fellow educators the following school year, Carter opened her staff meeting with the story of a jumping challenge that her daughter played with her Uncle Cliff. Uncle Cliff would raise his hand, and the 5-year-old would jump to it, pushing herself higher with each attempt. Then Uncle Cliff lifted his hand higher than the girl had ever reached. Her daughter quickly formed a plan. She ran, jumped on the couch, and tagged his hand, surprising everyone.

Carter’s point: “If you don’t raise the expectations, you don’t give them a chance to challenge or reach those goals. And we got 67% of our students at the independent reading level the next year.”

Carter’s point: “If you don’t raise the expectations, you don’t give them a chance to challenge or reach those goals. And we got 67% of our students at the independent reading level the next year.”

''If you don’t raise the expectations, you don’t give them a chance to challenge or reach those goals. And we got 67% of our students at the independent reading level the next year.'' - Syeda Carter.

https://bit.ly/45JPBPp Share on X

https://bit.ly/45JPBPp Share on X

The academy experience

Carter knew that raising expectations was just the beginning of the school’s efforts to universal student literacy, and she wanted to learn as much as she could to help her teachers get every student to proficiency.

In 2013, Carter applied and was accepted to the Learning Forward Academy, which brings together educator leaders with expert coaches to create successful and sustainable change in their educational systems. Over the professional learning program’s 2½ years, participants learn about and implement several system improvement tools, such as root cause analysis and theory of change, and work together on their individual problems of practice.

At the core of the academy is an understanding that educational improvement is iterative and requires continuous assessment, adaptation, and refinement, as well as ongoing learning among all educators in a system.

Carter’s academy learning turned out to be foundational to her career as an educator and to reaching her goal of getting 90% of 2nd-grade students to grade-level reading. It allowed her to apply and deepen her existing educational knowledge and skills while building new ones.

“I had this fire,” Carter says. “I had this passion, but I didn’t know how to connect things, like a big puzzle. I had the edges, but that middle was still developing. Learning Forward put those pieces in the middle and taught me how to connect them.”

She credits Dawn Wilson, one of her academy coaches, with giving her the tools to describe the work she was already doing and go even further with it. “Dawn gave me the language and helped me complete the puzzle pieces I didn’t see,” she said, adding that Wilson’s coaching “pushes you out of your comfort zone and challenges you with a soft voice.” Carter values her relationship with Wilson, a friendship that has lasted through the years.

Aligning the curriculum

Focusing on the literacy problem of practice in the academy helped Carter and her school take the next steps to improving student achievement: a new all-encompassing curriculum with a fresh assessment system. Previously, the school used a writer’s workshop approach with Lucy Calkins’ materials and a Fountas and Pinnell assessment program. “We had a lot of teachers all over the place,” Carter said. “They were grabbing and pulling from here and there.”

The school adopted the American Reading Company’s ARC Core, which integrates explicit foundational literacy skills instruction to build phonemic awareness, phonics, spelling, grammar, and vocabulary. “It gives us a common denominator,” Carter says.

With it, teachers have a clear instructional road map for science, social studies, literary genres, and writing across the disciplines. The school also uses the American Reading Company’s Independent Reading Level Assessment for literacy assessments. “We wanted something everyone would use that mapped to the standards,” Carter says.

Alignment and coherence were key for developing consistency throughout the school. To become skilled with the new curriculum, teachers participated in three days of professional learning over the summer with the American Reading Company and were paid for their time.

During the school year, additional professional learning was embedded in faculty and grade-level meetings, where Carter shared videos of her teachers assessing students using the Independent Reading Level Assessment. She also provided time for teachers to share strategies and activities aligned with the new curriculum.

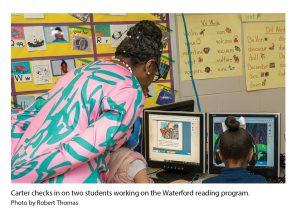

Sustained professional learning was essential for teachers to shift to more effective reading instruction because the approach was very different from what they had been doing previously. American Reading Company coaches continued to support curriculum implementation. “We had a coach come twice a month to be with (different) grade levels but also go into the classrooms,” Carter says. Coaches also worked with teachers to demonstrate how to assess the students with the Independent Reading Level Assessment and enter student data into the online performance management system.

Coaching became an ongoing priority for the school. The school continues to engage teachers in coaching through a combination of a Title I-funded expert reading specialist and American Reading Company-provided coaching.

Monitoring progress

With new instruction underway, Carter and her teachers were ready to monitor progress and make adjustments as needed. After analyzing student data from the Independent Reading Level Assessment, the coaches and teachers realized they weren’t where they wanted to be and needed to make significant changes in how teachers worked with students.

The assessment groups students into three categories of performance: emergency, at risk, and proficient or above. “What we found when we looked at the data was that the teacher would meet more with the students that were proficient or above,” Carter says. “It’s easier to meet with them, but the at-risk group was not getting the time and support needed to accelerate reading growth. We needed that to shift.”

The educators worked toward the goal of moving at least 40% of students from the emergency category to at risk and that same percentage from at risk to proficient or above. To do so, teachers have to know explicitly what every student needs to learn and meet more frequently with students in lower-performing reading groups.

Around the same time, an external equity audit by the New Jersey Network of Superintendents indicated that Carter needed to commit to implementing professional learning for her staff on how to ask students more higher-order thinking questions, engage students, and provide feedback that would allow students to improve learning skills for future lessons.

Carter set about honing her school’s professional learning. She gave educators collaboration time to develop reading assessment inter-rater reliability and shared expectations. Using extended common planning periods and grade-level meetings, teachers could also spend one-on-one time with coaches to assist with assessments and planning for instruction.

With support from the coaches, teachers adjusted their reading group meeting schedules to make this shift. Coaches also worked with teachers on the instructional practices that needed improvement.

Priorities Carter learned through the Learning Forward Academy provided her with the guidance to make these big shifts in curriculum, assessments, and professional learning. She modeled leadership by being willing to share data and develop strategies to assist teachers in improving student achievement. Encouraging rigorous lessons, teacher accountability, reflecting on practice, and, most importantly, being visible in the classrooms added to the instructional improvement.

Combatting absenteeism

Once the new curriculum was in place, one of the largest obstacles to achieving the reading goal was school attendance rates. Chronic absenteeism, tardiness, and the high student mobility rate hindered student success.

The school is in a high-poverty area where many residents’ housing situations change frequently. Many students don’t stay for a full year, Carter says, and about 32% of K-2 students missed 18 or more days in 2022-23, while 27% were late on 18 or more days.

To help families understand the need for consistent, on-time attendance, Carter showed slides at back-to-school night illustrating the academic differences between children who attended school consistently for two years and those who did not. Only 39% of students with 18 or more absences could read at or above grade-level proficiency versus 73% of students with good attendance. “If you bring them to my teachers, I promise your children will succeed,” Carter told the families.

One attendance improvement strategy that worked was to host surprise early morning all-school celebrations, sometimes with a DJ and dancing. When word got out, students didn’t want to miss out. “We had it on a Friday. The next Friday, we had 99% of the kids in school,” Carter says.

The pre-K-2 students depend on their parents for transportation, and Carter says, “It’s strategic because the kids become our advocates, begging their parents to get there and celebrate.”

Another strategy is attendance awards that encourage teamwork. Classes work to spell out the word “attendance,” one letter for each of the 10 months of school. “If students have 85% or more attendance, you color (the letter) in.” At the end of each month, Carter and her vice principal visit classes that met the goal with noisemakers and hand out attendance bracelets.

Building a lasting culture of reading

Threading through Carter’s work are other important initiatives that have contributed to achieving her schoolwide reading goal. One is her attention to building relationships with her staff and families. This includes fostering relationships between teachers and students’ families to establish trust and rapport between them.

Building relationships leads to an openness to learn, so when the staff talk with parents about the importance of reading and what early reading behaviors look like, the community is more open to receiving this information, Carter said.

With the school community, Carter has created a culture of reading where one didn’t exist. Teachers challenge their students to make reading-level goals and chart their progress. This way, students are aware of their current levels and expected end-of-the-year reading-level goals.

Today, the reading culture manifests in ways big and small. Books can be found everywhere around the school. When students are waiting in the hallway for the restroom, teachers have crates of books on hand for them to peruse. Every summer, Carter makes sure students have collections of books to take home.

Time to celebrate

As Carter and her team kept their focus on on-grade reading by the end of 2nd grade, they saw student proficiency go up, but reaching the reading goal would take time and persistence. At the end of the 2022-23 school year, nearly 90% of students completing 2nd grade met or exceeded grade-level expectations in reading — a significant increase from the 40% when Carter began as principal. Carter brought the staff together to mark the accomplishment.

Even though 13 years had passed since her time in the Learning Forward Academy, one of the first people Carter contacted was her academy coach, Dawn Wilson. “I was literally in tears. I had to call Dawn,” she said. Wilson remembers the phone call well. “She was elated,” Wilson said.

Carter and her staff keep working, learning, and leading because they know that ensuring all students are reading proficiently is not a one-time accomplishment. Carter stays closely connected to Learning Forward and has not missed a Learning Forward Annual Conference since her first one in 2013 because, she says, it helps her stay current in the field and connect with other learning leaders, colleagues, and friends.

In 2019, her academy experience came full circle when she signed on as a coach for a new cohort of academy members. “I’m always hungry and thirsty for knowledge. Learning Forward fills that void,” she says. Carter has also expanded her learning to doctoral studies.

“Our challenge now is to keep that (high achievement) trend and to sustain that over time,” she says of her school. She’s already thinking about placing the right person in her role to ensure the work continues when she retires someday. “It’s just too much work to go backwards,” she said.

Download pdf here.

About the Learning Forward Academy

The Learning Forward Academy is Learning Forward’s flagship deep learning experience, committed to increasing educator and leader capacity and improving results for students in the ever-changing landscape of education. For over 30 years, the academy has supported the problem-based learning of teachers, teacher leaders, instructional coaches, principals, regional leaders, superintendents, and others whose jobs involve supporting the learning of other adults and students. For more information, visit learningforward.org/academy.

References

Lesnick, J., Goerge, R., Smithgall, C., & Gwynne, J. (2010). Reading on grade level in third grade: How is it related to high school performance and college enrollment? Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Jefna M. Cohen is associate editor at Learning Forward.

Categories: Data, Outcomes, Reaching all students

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential...

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional...

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into...

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...