Shared vision leads to quality across the early grades

April 2021

Young children’s daily interactions with teachers are critical to the development of their social, cognitive, and self-regulatory skills (Hamre, 2014). But not all young children have access to the types of interactions that matter — interactions that are warm, supportive, cognitively engaging, and rich in core academic areas such as literacy, math, and science.

One barrier to ensuring all children have access to great teaching is the lack of a clear and shared vision of good instruction across the early grades from pre-K to 3rd grade. There is much that unites best practices across these grades, but, far too often, educators and parents assume that preschool is a time to focus on social and emotional skills while school really starts when children enter kindergarten and the focus turns to academics.

Research paints a different picture, showing that social, emotional, and academic skills are intertwined and we should nurture all of them over time (Jones & Kahn, 2017). To the untrained eye, a preschool classroom, with 4- and 5-year-olds spending the majority of their day at play, looks like a different universe than a 3rd-grade classroom, with 8- and 9-year-olds engaged in structured learning activities. But in truth, although the content of instruction changes substantially between preschool and 3rd grade, the process or the how of instruction should be very similar.

Adopting a shared vision of the teaching and learning process across grades can help ensure that more classrooms are high quality. Teachstone’s experience working with schools and districts around the country has shown us what this vision can be and how to make it come alive.

A shared vision

At the core, great teaching across the early years has three major components:

Effective teacher-child interactions that build strong relationships, promote positive behavior and engagement, and enhance cognition and language skills;

Content-focused instruction and learning opportunities in core areas, including literacy, math, science, and social-emotional skills; and

Individualized instruction based on a deep understanding of the social and academic needs of each student.

The best teachers bring these three elements together throughout the school day, seamlessly interweaving them and creating opportunities for learning in formal and informal moments of instruction. For example, effective preschool teachers provide structured opportunities to develop skills such as phonological awareness but reinforce them in small groups, centers, and play settings. Effective kindergarten, 1st-, 2nd-, and 3rd-grade teachers weave together content areas and recognize that children will best master skills if they attend to the ways that children’s social and emotional development impacts their academic learning.

Just as children’s development is a gradual progression in which skills become increasingly differentiated, so, too, should good instruction. Children should spend less time in highly structured literacy instruction in preschool than in later grades, and children’s growing skills in attention regulation means they can get more out of longer whole-group instruction as they mature.

When teachers and leaders work together across grades, they can learn from one another and plan strategically for how to create this progression. Professional learning communities, coaching, and other professional learning strategies can help embed the three elements of the shared vision and make transitions smooth for children.

What children experience

Unfortunately, most children don’t experience this gradual progression. Rather, they experience a stark shift as they move from preschool to kindergarten and beyond. And research suggests the vision for great teaching is far from a reality for most children in preschool through 3rd grade.

Children may get one or two components of quality at a time, but rarely all three. At the younger end of the continuum, too often preschool experiences are engaging but do not provide systematic exposure to core early academic skills. The pattern often flips once they enter kindergarten: Most children spend the majority of their time in rote and rather dull academically focused instruction.

One illustration of this huge shift between preschool and kindergarten comes from research conducted in Fairfax County, Virginia (Vitiello et al., 2020). Observers visited 117 preschool classrooms and 289 kindergarten classrooms. Most (72%) of the preschool classrooms were in school buildings, with the remainder in private child care settings.

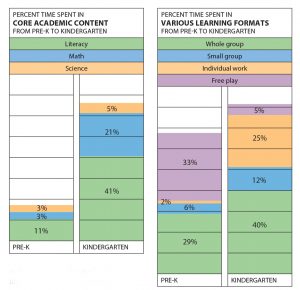

Children’s experiences shifted remarkably in one year, even though many of them remained in the same school building. As shown in the first graph on p. 23, preschool children spent only a small fraction of their overall day (17%) in the core academic content areas of literacy, math, and science. One year later, these same children were spending an average of 67% of their time in these content areas, with the majority of that time in literacy activities.

The format of instruction also shifted drastically, as seen in the second graph on p. 23. In preschool, children spent about a third of their time in centers or free play. By kindergarten, this was reduced to an average of 5% of their time, while time spent in whole group and individual seat work increased significantly.

In addition, the quality of teacher-child interactions decreased from preschool to kindergarten, based on data collected with the CLASS observational measure. (See box above for information about the CLASS.) This was true for all three dimensions of interaction quality measured, even instructional support, which one might have expected to be higher because the amount of academic content was more intensive.

Additional research (Bassok et al., 2016) and my own experience observing classrooms suggest these findings are not isolated to Fairfax, Virginia, but represent the reality for most children in the United States.

Another recent study that examined interaction quality from kindergarten to 3rd grade found that only 4% of children in the sample had access to classrooms with top-tier quality in emotional support and classroom organization and moderate quality in instructional support (Vernon-Feagans et al., 2019). In fact, over half of students never had access to that desired pattern of quality or only in one year from kindergarten to 3rd grade.

Furthermore, there was evidence that very poor students and Black students were even less likely to experience good teaching for multiple years. This is particularly troubling because those few students who did have access to such high-quality teaching across multiple years had stronger literacy skills by the end of 3rd grade.

Access to effective teaching

Clearly, there is a need for systematic work to help close these opportunity gaps and inconsistencies in children’s experiences from pre-K to 3rd grade. Teachstone has partnered with early childhood programs and school districts across the country to help them systematically focus on, measure, and improve children’s instructional experiences during these early years of schooling, using the CLASS. Although the approaches to this work vary, we see a few commonalities in successful initiatives.

FOCUS ON THE TEACHING THAT MATTERS MOST.

Classrooms and schools are complex places where educators are required to focus on many things. Effective educators hone their focus on the specific classroom interactions that are most critical to children’s learning and development.

CLASS helps educators focus improvement efforts across the most critical elements of the children’s classroom experiences, and the specificity of the descriptions of teaching elements help educators achieve alignment across grade levels, content areas, and curricular approaches.

MEASURE TEACHER-CHILD INTERACTIONS AND PROVIDE ACTIONABLE DATA TO EDUCATORS.

The most effective programs use CLASS not only as an accountability tool but also as a way to provide teachers, coaches and leaders with actionable data about what is going well and areas for improvement. We recommend conducting formal CLASS observations twice a year as well as more frequent informal observations by coaches or administrators.

For teachers, it is important that CLASS reports provide details on the types of interactions that were more and less effective so that they can focus their efforts to improve. (We often recommend emphasizing just a few dimensions at a time.)

For administrators at the school or district level, CLASS data help make important decisions about how to allocate professional development resources and can help track progress along the way. This is important as far too often we invest in professional development and have very little data on whether or not it is effective.

IMPROVE TEACHER-CHILD INTERACTIONS THROUGH INTENTIONALLY DESIGNED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING AND COACHING.

It’s simply not enough for teachers to read about or hear lectures on how to teach. They need to be able to see what it looks like in action and have tools and supports to analyze and improve their own teaching. Coaching is a highly effective method for supporting teachers to change practice, especially when coaches ask teachers to videotape themselves to pinpoint examples of positive interactions as well as moments for improvement.

One example of an evidence-based coaching program — one of the few to be included in the What Works Clearing House — is MyTeachingPartner (MTP), in which coaching cycles are driven by questions and observations based on the CLASS (Foster, 2019).

ALIGNING PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Adopting and implementing a shared vision of pre-K to 3rd-grade learning requires collaboration and capacity building among all leaders and staff. In addition to covering content on instructional format, professional learning should address how staff can develop deep connections with students and their families — a practice that is more common in the earliest years but should be expanded — and understanding of the ways in which children’s culture influences their learning and development.

Despite clear consensus on what makes professional learning effective, the majority of educators still spend their precious time engaged in brief and unfocused professional development experiences that simply do not work. Organizing professional learning around a shared vision of high-quality teaching across grades can benefit everyone — teachers, students, and the whole community.

Download pdf here.

In This Issue

UPDATES

Recent Issues

LEARNING DESIGNS

February 2025

How we learn influences what we learn. This issue shares essential resources for creating, facilitating, and assessing high-quality professional learning.

BUILDING BRIDGES

December 2024

Students benefit when educators bridge the continuum of professional learning between K-12 schools and other institutions.

CURRICULUM-BASED PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

October 2024

High-quality curriculum requires skilled educators to put it into practice. Professional learning can ensure instructional materials lead to excellent teaching and learning.

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue shows how professional learning helps educators pivot, by bridging the gap between knowing better and doing better.