FOCUS

Better than a buddy system: A framework for new teacher mentoring

By Leslie Ceballos, Thomas Manning and Sharron Helmke

Categories: Career pathways, Learning designs, Mentoring & inductionApril 2025

In the majority of schools, a new teacher assumes essentially the same responsibilities as an experienced one. This puts the novice teacher — and her students — at a significant disadvantage. New teachers often lack the real-world wisdom, experience, resources, and skills veteran teachers have gained from years of experience. Nationally representative data shows that one in 10 new teachers in the U.S. has no student teaching experience (Podolsky et al., 2016). Furthermore, in 2023 schools in 49 states plus the District of Columbia employed more than 360,00 teachers who were not fully certified, meaning they had little or no training prior to entering the classroom (Tan et al., 2024). To complicate the situation, schools without strong processes and commitments to ensure teachers engage in team-based, collaborative learning often leave teachers practicing alone and give them limited opportunities to share their experiences and learn with and from one another.

As a result, novice teachers report learning by trial and error. They develop coping strategies early on just to survive, without any guarantee that the strategies they are developing are productive or effective. This is a troubling situation for students and teachers alike. This process of learning by trial and error can leave some talented novice teachers feeling ineffective and disconnected until they eventually leave the profession, adding to worrisome trends of teacher attrition. Teacher attrition is particularly pronounced among young teachers — an estimated 17% to 30% of new teachers in the U.S. leave the profession within their first five years (Kini & Podolsky, 2016). A 2022 survey found that 38% of teachers aged 25-34 said they planned to leave teaching, and one of the primary reasons they gave was feeling unsupported (Bryant et al., 2023).

New teacher mentoring is a way to address that lack of support and boost teacher retention. A review of research on teacher mentoring and induction found that longer and more consistent mentoring programs result in higher teacher satisfaction, commitment, and retention, as well as improved skills in keeping students on task, developing workable lesson plans, and creating a positive classroom atmosphere. Additionally, teachers demonstrated stronger student questioning practices and more effective classroom management, and saw higher student scores or gains on achievement tests (Ingersoll & Strong, 2011).

We have seen the power of investing in high-quality mentoring firsthand. At Learning Forward, we developed an approach to mentoring shaped around a cycle of inquiry and support in which an experienced educator and a novice educator engage together. This approach is qualitatively different from the traditional “buddy system” approach to mentoring that is visible in many schools. Instead, it establishes mentoring as high-quality professional learning for new teachers, following a set of intentional steps to facilitate specific types of action, reflection, and improvement. We frame these steps as a cycle because they build on each other, and because mentors and mentees revisit them and repeat them multiple times as they work together over the course of a year or more. This early patterning then forms the basis of a new teacher’s career-long practice of continuous inquiry and learning.

The mentor cycle is grounded in research, the Standards for Professional Learning (Learning Forward, 2022), and Learning Forward’s experience designing and facilitating Mentor Academies around the globe. The first of these academies began in 2016 when the Louisiana Department of Education selected Learning Forward to design and facilitate an instructionally focused professional learning program for mentors. The program provided expert teachers across the state tools and skills to more effectively support teachers in their systems through their first three years of teaching. This partnership was completed in February 2020, with more than 1,600 mentor teachers participating. Ninety-five percent of all participating mentors reported feeling “prepared and confident to mentor resident and novice teachers.” Mentors indicated that by applying and sharing what they learned in the mentor teacher program they saw improvements in student performance as well as their own mentoring capacity and instructional practices (Manning & Bouffard, 2020).

THE MENTOR CYCLE

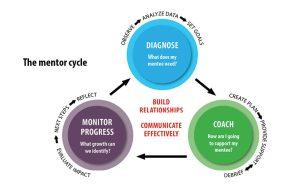

At the center of the mentor cycle are two components that are key to the entire process: building relationships and communicating effectively. Establishing and maintaining strong, trusting relationships with mentees drives all of the other work the mentor and mentee will do during the cycle. And as mentors and mentees work through the cycle throughout the school year, communicating effectively is vitally important when discussing various needs, providing support, and reflecting on learning. This requires mentors to be skillful at listening, paraphrasing, asking questions, and providing high-quality feedback.

The cycle begins with the diagnose phase. In this phase mentors are asking and then answering the question, “What does my mentee need?” They observe new teachers in their classrooms, analyze data on what they see and hear, and use evidence to set a learning goal with their mentees that will impact their teaching practice and their students’ learning.

The coach phase of the cycle has mentors answering the question, “How am I going to support my mentee?” In this phase mentors select from various types of support, from providing resources to classroom support through modeling or co-teaching. This phase also includes debriefing during and following the provided supports.

In the final phase, monitor progress, mentors are asking, “What growth can we identify?” Here mentors look at data from the support they’ve been providing to evaluate the impact of that work and determine the next steps for the new teacher. The mentor plans for and facilitates reflection conversations to develop the mentee’s capacity for self-analysis and to become a reflective practitioner committed to his or her own continuous improvement.

These three questions guide the work that is happening during each core component of the cycle. Mentors proceed through this cycle — diagnosing what teachers need, coaching and supporting them, and then figuring out what to do next — many times throughout their relationships with their mentees.

MENTOR SKILLS

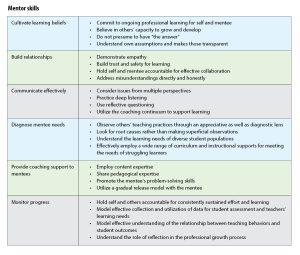

While engaging in the mentor cycle, mentors develop and deploy expertise in several key areas, some of which are particularly relevant for the three phases of the cycle and others that underlie the entire mentoring process. These skills are described in the table below.

Mentors use all the skills described above to work effectively with new teachers through what is often referred to as a gradual release of responsibility model. This is a common teaching structure that involves strategically using and then removing scaffold strategies to help children reach higher stages of development, but it can also be used with adults. The process generally occurs in three stages:

- I do it to model it. In this case, “it” can be a new instructional practice, a new classroom management skill, or another learning-focused activity.

- We do it together, so I can observe and support you.

- You do it, at first with others and then independently.

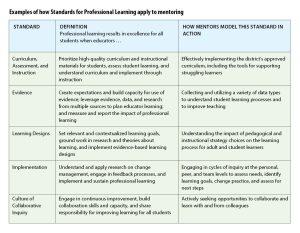

MENTORING AND THE STANDARDS FOR PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Throughout the cycle, effective mentors embody the Standards for Professional Learning (Learning Forward, 2022) both in their own professional learning and in the professional support they provide to novice teachers. For example, the Implementation standard tells us that educators should ground their professional learning work in research and theories about learning. This is critical for mentor teachers, as new educators may exhibit varying levels of expertise, confidence, or understanding of effective instruction. The science of learning — the application to educational practice of research on how students and adults learn — provides critical guidance for high-quality instruction and professional learning and, therefore, for the work mentors and mentees do together. Evidence-based design elements include active engagement, collaboration, meaning-making, inquiry, and reflection.

As another example, the Learning Designs standard says that professional learning results in the best outcomes “when educators understand and apply research on change management, engage in feedback processes, and implement and sustain professional learning” (Learning Forward, 2022). We have already touched on how some of these are reflected in mentors’ work, including commitment to ongoing professional learning and engaging in self-reflection.

The table below lists examples of how the Standards for Professional Learning relate to the mentor cycle.

A FOUNDATION FOR SUCCESS

Our upcoming book, Mentoring New Teachers: A Framework for Growth (Learning Forward, in press) is a step-by-step guide to building and applying these skills for all educators involved in planning, implementing, or supervising mentoring for new teachers. It can be used on its own or as part of a school-wide mentoring program. It also includes examples from Mentor Academies we have facilitated around the world.

In our experience, an effective, instructionally focused mentoring cycle fosters positive habits and ways of relating to colleagues and students. It provides the instrumental and social supports new teachers need, forms the bedrock of career-long beliefs and practices, and keeps them in the profession at a time when high levels of attrition are causing significant hardship for districts and the students they serve. Most importantly, this approach can expedite the improvement of novice teachers and thereby support improved outcomes for their students.

Download pdf here.

References

Bryant, J., Ram, S., Scott, D., & Williams, C. (2023). K-12 teachers are quitting. What would make them stay?McKinsey & Company. tinyurl.com/327edchk

Ceballos, L., Manning, T., & Helmke, S. (in press). Mentoring new teachers: A framework for growth. Learning Forward.

Ingersoll, R.M. & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201-233.

Kini, T. & Podolsky, A. (2016). Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of the research. Learning Policy Institute.

Learning Forward. (2022). Standards for Professional Learning.

Manning, T. & Bouffard, S. (2020). Mentors make a difference. The Learning Professional, 41(6), 20-23.

Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Learning Policy Institute.

Tan, T.S., Arellano, I., & Patrick, S.K. (2024). State teacher shortages 2024 update: Teaching positions left vacant or filled by teachers without full certification. Learning Policy Institute.

Categories: Career pathways, Learning designs, Mentoring & induction

Recent Issues

LEARNING COMMUNITIES FOR LEADERS

October 2025

Leaders need opportunities to connect, learn, and grow with peers just as...

MAXIMIZING RESOURCES

August 2025

This issue offers advice about making the most of professional learning...

MEASURING LEARNING

June 2025

To know if your professional learning is successful, measure educators’...

NAVIGATING NEW ROLES

April 2025

Whether you’re new to your role or supporting others who are new,...