For those who support teachers, it can feel like there are myriad urgent needs, especially when educators are stretched thin and students are struggling, as many are now. How do you prioritize your support, and where do you start?

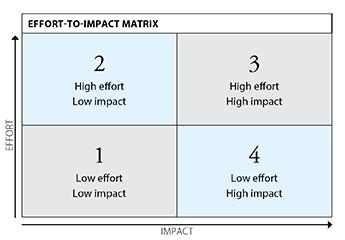

The effort-to-impact matrix is a simple but valuable tool that can help instructional coaches, teacher teams, administrators, and other change agents prioritize their efforts and make strategic choices about which steps to take and when. It allows the user to map out potential strategies and identify how much effort each will take versus how much impact it is likely to make.

The matrix is divided into four quadrants. (See figure below.)

Quadrant 1 refers to low-effort, low-impact strategies. Strategies in this quadrant don’t require much educator effort, but they also are likely to produce few improvements in student outcomes. These strategies often leave the learning leader wondering why he or she should bother. That doesn’t mean that the strategies are useless, but they are unlikely to make meaningful changes in teacher practice and student outcomes. Examples might include redesigning bulletin boards or changing lesson planning templates for administrative purposes.

Quadrant 2 is for high-effort, low-impact strategies. They require much effort on the part of teachers and perhaps other staff but have little impact on student outcomes. Strategies in this quadrant often lead participants to wonder, “Whose idea was this anyway?” An often-cited example is filling out binders of professional learning community documentation that teachers perceive as being unrelated to the actual work of the team or their teaching efforts.

Quadrant 3 is for high-effort, high-impact strategies. Coaching cycles or change initiatives in this quadrant take cognitive heavy lifting. They take time to investigate, learn, practice, and implement with consistency and fidelity, but they make an obvious difference for most or all students.

Examples of Quadrant 3 activities include instructional changes such as ensuring that all members of teacher teams have a common planning period or moving a teacher whose comfort zone is whole-class direct teaching to a more interactive approach that incorporates student groups and independent practice.

While Quadrant 3 activities produce big wins for teachers and students, they require intensive efforts to produce results that unfold slowly over time, and they can leave teachers and coaches feeling overwhelmed and burned out.

Quadrant 4 strategies are low effort, high impact. They can be considered quick but effective wins. Strategies in this quadrant may result in small changes that add up quickly and make a noticeable difference in student outcomes. Examples include improving classroom management and implementing more effective student grouping strategies, both of which can help maximize instructional time while also decreasing teacher stress and improving teacher efficacy.

Different combinations of effort and impact make sense in different situations. For example, during especially challenging times, such as during post-pandemic recovery, focusing on small, quick wins (low effort, high impact) can make professional learning feel manageable and increase teacher buy-in. During more stable times — for example, when the district has stable leadership and an influx of grant funding — professional learning leaders might choose to focus more on high-effort, high-impact strategies.

An effort-to-impact matrix can also help professional learning leaders sequence their support over time. Consider, for example, the value of building momentum with several low-effort, high-impact cycles. This can build teachers’ interest in and commitment to coaching. That might open the door to a single high-effort, high-impact cycle. Following that push, the district might choose to ease off, using a few more low-effort, high-impact cycles to keep the pace and load manageable for teachers.

Click here to use the tool to create your own effort-to-impact matrix.