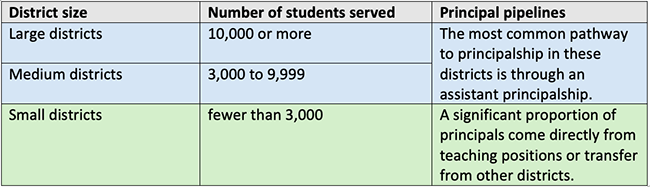

More than 70% of school districts in the U.S. serve fewer than 3,000 students (NCES, 2022), and a recent study found that those districts are less likely than larger districts to provide school principals with the supports to be effective leaders (Diliberti et al., 2024). This has concerning implications for the more than 35% of American students enrolled in small districts, because research shows that school leadership is a critical factor in improving teaching and learning. Principals are second only to teachers among in-school factors that impact student achievement (Grissom et al., 2021). Great principals are made, not born, and the study suggests they’re less likely to be made in small districts.

Research shows that strong school leadership can be cultivated through well-designed principal pipelines – systems for hiring, supporting, and evaluating school leaders (Gates et al., 2019) that are consistent with the principles of high-quality professional learning as outlined in Learning Forward’s Standards for Professional Learning (Learning Forward, 2022). These pipelines are associated with a 6 percentile point increase in student reading achievement and an almost 3 percentile point increase in math achievement (Gates et al., 2019).

But based on a nationally representative survey of 156 district leaders, researchers from RAND found that large and medium districts tend to have more developed and systematic principal pipelines than small districts. Overall, 76% of large districts reported engaging in at least one aspect of a high-quality principal pipeline, compared with 54% of medium districts and only 41% of small districts.

That means that students in small districts attend schools where leaders might have fewer of the supports that have been shown to improve math and reading achievement. The research points to some concerning gaps and potential areas for improvement in principal professional learning and support.

Principal supports and pathways vary across districts

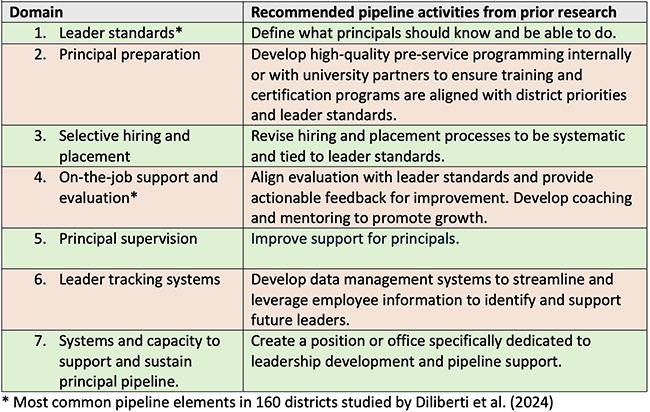

Research sponsored by The Wallace Foundation over almost 15 years has revealed seven domains of effective principal pipelines, shown in the table below, that are associated with gains in student reading and math (Gates et al., 2019). These domains are aligned with the Standards for Professional Learning (Learning Forward, 2022), especially the Leadership and Professional Expertise standards.

Domains of Principal Pipeline Activities

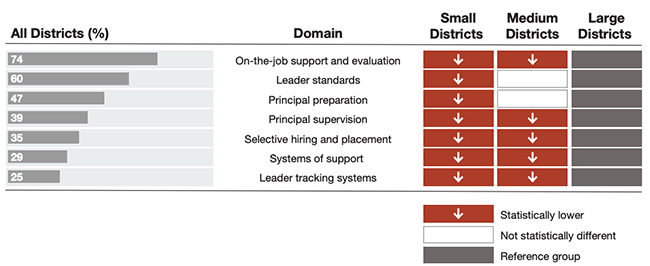

RAND’s study shows notable differences in every domain according to district size. Small districts were significantly less likely than large districts to engage in every aspect of the pipeline, and medium districts were significantly less likely than large districts to engage in every aspect except two.

Summary of Districts’ Principal Pipeline Activities as of the 2023-24 School Year

Source: Diliberti et al. (2024)

The study also found differences in leaders’ paths to the principalship. In medium and large districts, the most common pathway to becoming a principal is to serve as an assistant principal first. In small districts, by contrast, principals tend to transfer from other school systems or come directly from teaching positions.

Large gaps in infrastructure underlie pipeline discrepancies

Taken together, the findings about career paths and pipeline components mean that principals in small districts are less likely to begin their jobs with school leadership experience and less likely to benefit from the pipeline components that have been shown to make a difference for student achievement. This is cause for concern. Although some of the pipeline components may not be relevant for small districts, such as leader tracking systems that help district staff identify and monitor support for prospective principals, others are very important, including leadership standards and coaching support.

One of the reasons for these differences is straightforward. As the researchers write, “there is a gulf between the infrastructure that large districts have compared with that of medium and small districts” (Diliberti et al., 2024, p. 12). Small districts may not have enough students or schools to hire staff such as assistant superintendents who are dedicated to overseeing principals, for example.

The researchers recommend that small districts look to other entities such as principal associations and principal preparation programs for support and resources such as samples of principal standards. In addition, The Wallace Foundation’s Principal Pipeline Initiative has developed resources that can be used by districts of all sizes and types, including a Principal Pipeline Self-Study Guide for Districts (Aladjem et al., 2021) and a planning guide (Goldring et al., 2023).

Learning Forward has found that regional and national networks are another valuable source of support. Networks bring together educators from across locations, either virtually or in person, to share problems of practice, engage in intentional learning cycles, and provide mutual support. We have found that our networks reduce geographic isolation, improve educators’ knowledge and skills, and are linked to positive student outcomes. For example, schools in Pasco County, Florida, participating in a leadership team network are seeing increases in middle schoolers’ ELA, math, and science scores, including a 14% increase in 6th graders’ ELA scores (Collins, 2025). Students in Montgomery County, Maryland, whose schools are participating in a curriculum-based professional learning network have shown an increase in math proficiency from 9% to 52% in one marking period (Foster, 2024). Both of these networks have included school leaders and their success shows it’s feasible and effective to facilitate shared networks of support for principals.

The RAND researchers call for additional investigation into which pipeline components are most impactful for small districts and how to conduct a condensed version of principal pipelines. Continuing to shine a spotlight on small, and often rural, districts can help ensure that all school leaders have the support they need to guide excellent teaching and learning for all students.

References

Aladjem, D. K., Anderson, L. M., Riley, D. L., & Turnbull, B. J. (2021). Principal pipeline self-study guide for districts. Policy Studies Associates, Inc.

Collins, C. (2025). Student achievement gains in Pasco County Schools. Learning Forward blog.

Diliberti, M. K., Schwartz, H. L., & DiNicola, S. E. (2024). How School Districts Prepare and Develop School Principals: Selected Findings from the Spring 2024 American School District Panel Survey. RAND.

Foster, E. (2024). Maryland students make math gains, powered by educator professional learning. Learning Forward.

Gates, S., Baird, M., Master, B., & Chavez-Herrerias, E. (2019). Principal Pipelines: A Feasible, Affordable, and Effective Way for Districts to Improve Schools. RAND.

Goldring, E., Rubin, M., Rogers, L., Neumerski, C. M., Moyer, A., & Cox, A. (2023). Planning and Developing Principal Pipelines: Approaches, Opportunities, and Challenges. The Wallace Foundation.

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research. The Wallace Foundation.

Learning Forward (2022). Standards for Professional Learning. Author.

National Center for Education Statistics (2022). Number and percentage distribution of regular public school districts and students, by enrollment size of district: Selected school years, 1979-80 through 2021-22. U.S. Department of Education, Institute for Education Sciences. nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_214.20.asp