FOCUS

A dashboard view of coaching

Digital log zooms in on coaches' daily activities

By Lauren B. Goldenberg, Violet Wanta and Andrew Fletcher

Categories: Coaching, Data, Research, Resources, TechnologyDecember 2019

Vol. 40, No. 6

Early literacy is the foundation of academic success and predicts outcomes far beyond elementary school. So when only 30% of 3rd graders in New York City public schools scored proficient on the state test in 2014, district leaders began targeting improvements in literacy instruction in grades K-2.

In 2016, the New York City Department of Education rolled out a major investment in early literacy called Universal Literacy. The district placed nearly 500 reading coaches in almost 700 schools to provide job-embedded coaching for K-2 teachers.

Coaches, who report to the district’s early literacy office and work in close collaboration with principals and teachers, focus on research-aligned reading instruction and are at the heart of Universal Literacy’s approach to increasing the percentage of children reading at grade level by the end of grade 2.

Early in the initiative, we — a central office administrator and a small internal evaluation team — realized we needed a mechanism to capture at scale what these instructional coaches do with teachers on a daily basis. It was imperative to find a way for coaches to discuss and report on their work and to ensure use of what Kane and Rosenquist (2019) call “potentially productive coaching activities” — those that research shows are likely to lead to refining teacher practice.

While coaches typically share their planned schedules with supervisors and keep detailed narrative records about coaching cycles, these do not necessarily reflect a day-to-day account of their work. Moreover, aggregating narrative coaching reports would yield little useful or actionable information.

To address the gap, we began a collaboration between the early literacy team and the district’s research office to develop and implement what became known as the digital daily coaching log.

A digital daily coaching log zooms in on NYC coaches’ daily activities. #LearnFwdTLP Click To TweetThe Digital Daily Coaching Log

Coaches complete the online digital daily coaching log every day they are in schools. The log captures information about how coaches spend their time — for example, coaching teachers, working with school building leaders, and providing professional learning sessions.

This is important because the ways coaches understand the focus of their work and allocate their time across tasks varies, despite strong research evidence about the importance of spending time working with teachers (Elish-Piper & L’Allier, 2011; L’Allier, Elish-Piper, & Bean, 2010).

Depending on the school they work in — the leadership, the culture, and the needs — or their own preferences, coaches might prioritize working with students, collecting and analyzing data, gathering and organizing instructional resources, and administrative activities over coaching teachers in classrooms (Bean, Draper, Hall, Vandermolen, & Zigmond, 2010; Deussen, Coskie, Robinson, & Autio, 2007).

The discrepancy between expectations of coaches and the reality of their work has surfaced in several studies of coaching (e.g. Bean et al., 2010; Kane & Rosenquist, 2019). In one study of Reading First, coaches were explicitly asked to spend 60% to 80% of their time in the classroom with teachers or working with teachers directly on their instruction, but while coaches dedicated long hours to their jobs, they spent on average only 28% of their time working with teachers (Deussen et al., 2007).

In the digital daily coaching log, coaches select the individual teachers or groups they worked with and then note the reading content and pedagogical areas of focus as well as the coaching moves they employed, e.g. visiting and debriefing, modeling, or side-by-side coaching. The coaches — all former district teachers who have been extensively trained by the district’s early literacy team — focus on and record instructional practices and principles outlined by the National Reading Panel (2000).

While the specific instructional focus varies from classroom to classroom, based on schools’ chosen curricular materials as well as teachers’ goals for their coaching cycles, the practices are always research-based. Because the district’s central office endorses curricular materials and provides incentives for adoption, but does not dictate use of particular materials, coaches are prepared to use research-based practices that apply across curricula.

For instance, coaches are able to work with teachers on how to effectively implement phonics lessons, regardless of the specific curriculum, so they can tailor their support to align with the materials teachers use. As an example, some coach-teacher pairs focus on implementation of the curricular materials used in their classrooms such as the supplemental phonics program Fundations.

Designing the log

From the beginning of the design process, we have aimed for the log to be what Yeager and colleagues (2013) call a “measure for improvement,” a practical tool that is a regular part of coaches’ work flow and results in usable information. Our goals were for the log to be user-friendly and the dashboard actionable. We iterated on the design, testing each version and remaining attentive to how the log fit into and reflected coaches’ daily work.

Each year, we undergo a revision process to ensure the log is representative of coaches’ day-to-day activities, aligned with the initiative’s evolving policies and language, and as streamlined as possible. The current version of the log consists almost exclusively of check-off items and typically takes less than 10 minutes to complete.

One of the lessons we learned after the first year was that coaches and program leadership needed more ready access to their data. Our goal was to promote continuous improvement among coaches by providing them with data they can use to reflect on and adjust their practice, but the first survey tool required the evaluation team to process raw data and create spreadsheets for each coach.

In the second year, we switched to a survey tool that had built-in dashboard functionality, streamlining the process of getting data in the hands of coaches and leadership.

Measuring coaching time

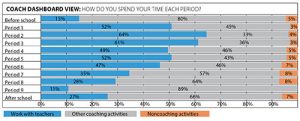

Coaches use data reports for conversations about their work with school building leaders as well as with their instructional supervisors. (Log data aren’t used to evaluate coach performance.) To facilitate discussion about how much time coaches spend with teachers, the dashboard view in the figure above visually shows coaches how much time they spend with teachers by period.

This view allows coaches to consider whether there are additional times during the day they can use for classroom coaching. Inspired by economic nudge theory (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008), we refer to this view as a “research nudge.”

Over our initiative’s first three years of implementation, the average time coaches spend with teachers has consistently hovered at around 40% of their time in schools. Several factors constrain the total amount of time coaches can be in classrooms — for example, coaches work a longer day than the classroom teachers, and, in some schools, reading instruction in all classrooms occurs within the same 90-minute block of time.

Still, some coaches are managing to work with teachers more than others. In the 2018-19 school year, log reports show that coaches reported spending between 14% and 76% of their time in schools with teachers.

Other uses of the log

During professional learning sessions, coaches have time to explore and reflect on other aspects of their log data using data protocols. For instance, in one session they considered whether they were using instructional coaching moves strategically and focusing on the right foundational reading skills, based on student assessment data. They also investigated the breadth and depth of their coaching across the K-2 classroom teachers in a school.

The log also promotes improvement at scale by providing a common language among coaches, their supervisors, and central office staff — a benefit we did not anticipate. It gives coaches a mechanism to codify their complex work in ways that allow them to reflect on how they can improve their coaching work at a building level.

At the same time, it affords coach supervisors and program leaders an aggregate view across coaches and schools, letting them consider variations to better support coaches and help advocate for systemic change in reading instruction, curricular materials (e.g. the use of a supplemental phonics program where needed), and fidelity in the use of reading assessments.

For example, at coach professional learning sessions, the district’s early literacy director referenced average time spent on each coaching move to encourage more active strategies such as modeling, co-teaching, and side-by-side coaching. He also cited the data coaches reported on their foundational literacy skills foci — the five pillars described by the National Reading Panel and the Institute for Education Sciences (NRP, 2000; Foorman et al., 2016), plus writing — to emphasize the importance of phonological and phonemic awareness.

Log implementation uncovered tacit assumptions about the initiative’s theory of action, as well as coaches’ assumptions about professional learning and school capacity building. For instance, deciding which teachers to list in the log provoked discussions about what high-leverage coaching looks like. Should long-term substitutes receive job-embedded coaching cycles? How about paraprofessionals? These discussions led to policy decisions, with room for variation in individual contexts.

Although the main focus of the log is as a measure for improvement, the evaluation team also aggregates log data to create briefings for policymakers, inform program design and development, and use for program evaluation.

Unlike school-level measures such as standardized test scores, which are lagging indicators and often fail to detect the early changes that may be indicative of larger gains later on, coach log data can be considered a leading indicator, allowing us to identify the amount of coaching teachers receive.

Consequently, we can investigate whether students of coached teachers make more gains on an outcome measure of reading. For example, we can explore relationships between how much coaching teachers receive and student achievement.

Reflections

We created the digital daily coaching log to do two things: track the everyday activities of reading coaches and collect data to inform practice and policy. From the outset, it has been important to recognize what the log can and cannot accomplish to set expectations and avoid pitfalls.

Coaches record their time, and we hope that because the data aren’t used for individual accountability, coaches are as honest as possible. We are also clear that the log does not capture the quality of coaching interactions. With these caveats, we have found the log to be a valuable tool with immense promise.

We encourage districts involved in instructional coaching, particularly those grappling with creating coherence at scale, to implement a similar strategy. Using an off-the-shelf survey tool and a collaboration between the instruction and data teams, it is eminently attainable.

An example of how one coach uses the log

Toward the end of an eight-week coaching cycle, the reading coach worked with a 1st-grade teacher on implementing targeted word-work within guided reading groups. A small group of students sat on a rug in the front of the room, practicing “tapping” out the individual sounds in words like “red” and “ham” while sorting the cards into two columns (short a and short e).

Using side-by-side coaching, the reading coach provided quiet instructions to help the teacher get the most out of her time with this small group of students.

At the end of her day, the reading coach completed the digital daily coaching log. When she recorded her work with the 1st-grade teacher, she noted the reading content (e.g. phonemic awareness, phonics); research-based pedagogical practices (guided reading, centers/stations), and instructional coaching activities (side-by-side coaching).

At a later date, she might use the log’s data dashboard to reflect on her work across all 1st-grade teachers in terms of reading content and pedagogical practices, as well as noting how much she has worked with each teacher.

We created the digital daily coaching log to do two things: track the everyday activities of reading coaches and collect data to inform practice and policy.

References

Bean, R.M., Draper, J.A., Hall, V., Vandermolen, J., & Zigmond, N. (2010). Coaches and coaching in Reading First schools: A reality check. The Elementary School Journal, 111(1), 87-114.

Deussen, T., Coskie, T., Robinson, L., & Autio, E. (2007). “Coach” can mean many things: Five categories of literacy coaches in Reading First (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007-No. 005).

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, and Regional Educational Laboratory Northwest.

Elish-Piper, L. & L’Allier, S. K. (2011). Examining the relationship between literacy coaching and student reading gains in grades K-3. The Elementary School Journal, 112(1), 83-106.

Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C.A., Dimino, J., … & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Kane, B.D. & Rosenquist, B. (2019). Relationships between instructional coaches’ time use and district- and school-level policies and expectations. American Educational Research Journal, 56(5), 1718-1768.

L’Allier, S., Elish‐Piper, L., & Bean, R.M. (2010). What matters for elementary literacy coaching? Guiding principles for instructional improvement and student achievement. The Reading Teacher, 63(7), 544-554.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups (NIH Publication No. 00-4754). Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Thaler, R.H. & Sunstein, C.R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Yeager, D., Bryk, A.S., Muhich, J., Hausman, H., & Morales, L. (2013). Practical measurement. Stanford, CA: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Categories: Coaching, Data, Research, Resources, Technology

Recent Issues

TAKING THE NEXT STEP

December 2023

Professional learning can open up new roles and challenges and help...

REACHING ALL LEARNERS

October 2023

Both special education and general education teachers need support to help...

THE TIME DILEMMA

August 2023

Prioritizing professional learning time is an investment in educators and...

ACCELERATING LEARNING

June 2023

Acceleration aims to ensure all students overcome learning gaps to do...