Educators and quality-management practitioners in other professions often speak of improvement, learning, or change as happening in a cycle. In its most basic form such a cycle occurs when active learners — whether adults or children — observe the world around them, take action based on what they understand, and then reflect on what happened before they plan their next steps, usually modifying their actions to better achieve the results they seek. This excerpt from Becoming a Learning Team explores setting the context for establishing a teacher learning team cycle.

Teachers may bring their individual learning to bear on activities in classrooms and schools, but the more they can apply and refine that learning within a collective activity, the more quickly the culture of continuous improvement grows. When teachers seize opportunities to create, lead, and learn in teams, they and their students benefit — if the teams understand how to frame the purpose and focus of their work.

After all, a mandate to collaborate may begin a team’s work together, but it will not help them achieve success. Michael Fullan has drawn attention to the fact that collaboration too often is structured without the intentionality required to get positive, measurable student results (Hirsh, 2016). The learning cycle creates such a structure: It promotes “collaboration and collective responsibility within a teacher team by setting up structures for short-term cycles of improvement” (Michigan Department of Education, n.d.). Plan, do, reflect is a commonly used three-step cycle, and a well-known four-stage cycle, also known as the Deming Cycle, is the plan, do, check, act cycle (American Society for Quality, n.d., para. 3). Bruce Wellman and Laura Lipton (2009) advance their Collaborative Learning Cycle of activating and engaging, exploring and discovering, and organizing and integrating (p. 5).

Learning Forward’s Standards for Professional Learning put a cycle of continuous improvement at the heart of collaborative learning. The standards embody a belief that a learning team cycle is the day-to-day means for embedding professional learning in classrooms, thus supporting teachers when they need it most. There are many forms of learning cycles, cycles of inquiry, or cycles of continuous improvement. Within professional learning in education alone, educators can find several examples.

In their professional learning community work, the DuFours and Robert Eaker (2008) have said that a learning team collaborates to determine

(a) What is it that they want students to know?

(b) How will they know if students know it? and

(c) What will they do if students do know or don’t know it?

To learn the answers to those questions, DuFour and colleagues (2010) note that learning communities use a cycle of inquiry that includes five stages: gathering evidence of student learning, developing strategies to address weaknesses and strengths in that learning, implementing new strategies, analyzing the impact of new strategies, and applying new knowledge in the next cycle of continuous improvement (DuFour, DuFour, Eaker, & Many, 2010).

Inquiry cycles are central to both lesson study and action research learning designs, for example. In lesson study, teams of teachers focus intently on specific classroom lessons. They consider carefully which short- and long-term student learning goals to emphasize, collaboratively plan a lesson, teach the lesson while colleagues observe, and then discuss and revise the lesson based on what they learn about the results of the lesson and its effect on student learning; often, other team members teach the next iteration (Lewis, 2014). In action research, Richard Sagor (2000) outlines a seven-step process that begins with selecting a focus and continues through clarifying theories, identifying research questions, collecting data, analyzing data, reporting results, and taking action informed by what teachers learn from data analysis.

The National School Reform Faculty (2014) also promotes a cycle of inquiry for professional learning, developed by the Southern Maine Partnership. The stages are analyzing data, framing or reframing key issues, investigating literature and expertise, developing an action plan, and carrying out strategies and collecting data.

Finally, in Anne Jolly’s (2008) Team to Teach: A Facilitator’s Guide for Professional Learning, learning teams use a collaborative decision-making cycle with the following steps: identify student needs, examine studies and research, engage in rigorous reflection, use research and wisdom to make good choices, collaboratively experiment with new teaching practices, monitor and assess implementation, communicate information to other stakeholders (p. 29).

These examples are not exhaustive, but they demonstrate the field’s widespread support for an iterative process that deeply engages educators in the work of studying student needs, preparing lessons, assessing their own knowledge, and reflecting on specific practices to inform next steps. Such cycles offer meaningful opportunities for teachers to put student understanding front and center, inquire collaboratively into what they as educators know and don’t know how to do, and discuss their impact on student learning. Teachers using a learning team cycle begin with a plan that anticipates how their learning and instructional choices will affect what students know and are able to do. They will adjust those plans as they build skills, knowledge, and dispositions while they move through the cycle.

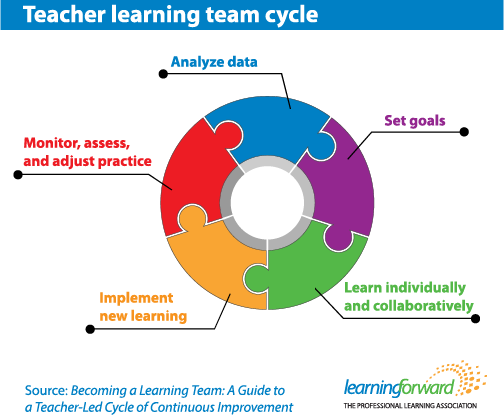

What is the learning team cycle?

Becoming a Learning Team describes a five-stage process aligned with Learning Forward’s Standards for Professional Learning to guide the learning team’s work, and examines the stages and procedures to implement them in more detail.

The above is excerpted from Becoming a Learning Team by Stephanie Hirsh and Tracy Crow. Read more about the book.

References

American Society for Quality (ASQ). (n.d.). Continuous improvement. Available at https://asq.org/learn-about-quality/continuous-improvement/overview/overview.html.

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2014). Teachers know best: Teachers’ views on professional development. Available at https://k12education.gatesfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Gates-PDMarketResearch-Dec5.pdf.

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (2008). Revisiting professional learning communities at work: New insights for improving schools. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R. & Many, T. (2010). Learning by doing: A handbook for professional learning communities at work, Second edition. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Hirsh, S. (2016). Michael Fullan affirms the power of collective efficacy. [Weblog]. Available at https://learningforward.org/publications/blog/learning-forward-blog/2016/04/20/michael-fullan-affirms-the-power-of-collective-efficacy#.

Jolly, A. (2008). Team to teach: A facilitator’s guide for professional learning. Oxford, OH: National Staff Development Council.